“There is African time,” said Nana Sule, host of the Kano International Poetry Festival (KAPFEST), “and there is Kano time”. These were her opening words at the previous year’s event, as the commencement was delayed by logistical issues, likely stemming from a paucity of funds, faced by the curating team. This year, however, there was no delay, and no need for apologies. That alone signaled the start of something special.

KAPFEST may be the name, but what unfolded in Kano was far more than a poetry festival; it was a vibrant cultural extravaganza and more. A fact no devout attendee would dispute. Now in its second year, the festival gathered over 50 poets, writers, journalists, musicians, artists, and thinkers to celebrate poetry, connect, and share stories. Under the theme “Poetry in a Time of Crisis,” KAPFEST 2025 featured a fantastic program of panel discussions, book chats, cultural performances, poetry and music, bringing Kano to a standstill for three days of cultural immersion from September 11th to 13th.

The journey to this unprecedented accomplishment began in April, days after Eid al-Fitr, when about 50 literati from Kano and beyond gathered for a mini-festival dubbed KAPFEST 2.0 EID POP UP. It was a preview of what was to come, featuring an open mic, book chat, and panel discussion. There, the main festival’s theme was unveiled. We shared food and conversation, packing the entire experience into four vibrant hours, 2-6pm.

Five months later, the main festival arrived with such powerful momentum that it left us in a state of awe and excitement. The mini-festival had indeed under-promised, for the main event spectacularly over-delivered, surpassing all expectations. In a post-KAPFEST social media post, the festival headliner, Dike Chukwumerije, awestruck by what he witnessed in Kano, described the event with the popular pidgin phrase: “small nyash dey shake.”

The first day began with simultaneous activities: online panel discussions, workshops at the festival’s poetry clinic, and a separate session for high school students. At the clinic, four poets – Ismail Bala, Ibrahim Malumfashi, Ifeanyichukwu Eze, and Abba Musa Idris – served as consultants, offering critiques on poems submitted by 20 young writers whose work had been selected from a torrent of submissions. The session was intense and intimate, a true tete-à-tête between curious mentees and passionate mentors. If one looked carefully, as I did, the smiles on the poets’ faces at the end could suggest only one thing: they had found successors to whom they could pass the bastion of their craft.

The afternoon of the first day was planned for taking the guests out to meet and explore Dabo’s Kano, the elephant’s belly. They visited Dala, the origin of the city and climbed its hill, which generously reveals the city’s expanse to those who seek the view. They visited Gidan Makama, the city’s museum, went to the Emir’s palace, Kurmi Market and Kofar Mata Dye pit. The festival guests encountered Kano, Nigeria’s uniquely vibrant city with neither “morning” nor night life.

The late afternoon was reserved for the community performance. If the festival had earlier detoured to the brink of tourism, it now plunged headlong into the pit of entertainment and sports. The community gathered at Gidan Dan Hausa on Sokoto Road, where four large white canopies shielded the audience from Kano’s oppressive sun. Two were placed to the west, with one each to the south and north, creating a C-shaped enclosure open to the east, where the stage stood. Red Turkish mats were spread across the ground, and the audience, waiters of promised thrill, sat upon them eager like the men, women and children in Cyprian Ekwensi’s An African Night’s Entertainment.

We had anticipated an open mic, traditional dance, and music. But there was more: the dambe. This Hausa mixed martial arts performance took us by surprise. Unlike Western bouts held in rings and cages, here the spectators formed the cage, and the sand was the ring. Only the punching hand was gloved. The two fighters were of unequal size, one skinny and tall, the other chubby and shorter. Cheered by the crowd and energized by the scintillating commentary from ex-BBC journalist Fatima Zahra and writer Yahuza Garba, whose words recalled ancient griots and raconteurs, the evening felt like a journey a thousand years into the past.

After about 20 minutes of fighting, both fighters had swollen faces. The skinny fighter almost sent his chubby opponent to the canvas with a vicious punch, while the chubby fighter also had a good go at his opponent. Finally, the veteran journalist, now a presidential spokesperson, Abdulaziz Abdulaziz separated the fighters, declared the bout a draw, and presented gifts to both.

The poet and calligrapher Qalbsaleem took the stage and tantalized the audience with a love poem. His performance earned him the new crown of “Chief Romantic Northern Man,” dethroning last year’s king, Richard Ali, who had been enthroned at the Kaduna Books and Arts Festival. This coup was spearheaded by Fatima Zahra. Later, Hidaya Mahmoud Muhammad’s performance of her slam-winning viral poem, “Kano,” resonated deeply, sending the audience into a frenzy. It was a fittingly electrifying cap to the late afternoon before music performances ended the day. Perhaps awed by the day’s events and the city’s vibrance, Fatima Zahra took to social media to declare Kano as nothing but “Lagos in a Kaftan.”

As I arrived at the gate of The Avenue, the festival venue on Murtala Muhammad Way near the Kano Club roundabout, I first saw Salim, the tall and slim founder of the Poetic Wednesdays Initiative standing with a lady I can no longer recall. He was dressed in black crested T-shirt and pants. A pointer that he was there for long and working. To the right was the attendees’ registration desk; to the left, four canopies were erected in an L-shape for vendors. Though the event had not yet officially commenced, the air was filled with a sense of readiness as everyone utilized the moment for networking and reunions. Inside, the stage was set. The hall was big, dim, and beautiful, its ceiling adorned with mighty chandeliers that authoritatively asserted their ornamentation whenever they met our gaze.

It was the second day. The day of speeches, chats, panel discussions and poetry slam. The chats and panels were a marriage between arts and advocacy. But before then, the opening ceremony. In her address, the poet Nasiba Babale, who doubled as the festival’s co-curator and the creative director of Poetic Wednesdays Initiative, said while making a case for poetry as a potent tool for advocacy, “with poetry, we can start conversations that can document what we are going through, we can evoke feelings and force the world to look at things it would otherwise turn its head against,” and also expressed how the craft can serve as a therapy. “We can always find succour in poetry, even in hard times, we can find healing and meaning in words, art, and music”.

Remarks were delivered by the Executive Secretary of the Kano State History and Culture Bureau, as well as by the Kano-born veteran journalist and scholar, Dr. Bala Mohammed. The Lagos-based poet Tobi Abiodun then sparked the event to life with an electrifying love poem before Hidaya Mahmoud sent the audience into a frenzy with her poetic performance on the festival’s theme.

A castle for poetry now stands firm in Northern Nigeria, inhabited by a growing royalty of talented voices. This flourishing did not happen by chance. It was built by those who shouldered the burden of nurturing talent and providing a stage for it to thrive. The signs of this renaissance are clear: two of the three finalists for the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature the last time it focused on poetry were Northerners. Adding to this prestige is Maryam “Alhan Islam” Bukar, the first poet ever appointed by the UN as a peace advocate ambassador, who also hails from the North. In recognition of his pivotal role in this movement, BM Dzukogi was presented with a well-deserved lifetime achievement award at KAPFEST 2.0.

Following the award presentation, the event’s first panel discussion commenced. Hosted by podcaster Misbahu El-Hamza, the panel featured Ismail Auwal, a Kano-based reporter for the New York Times, and Sabiqa Bello, a poet and journalist with Humanangle. They delved into the ethics of conflict reporting, focusing on the challenge of reporting the truth while avoiding the trap of becoming a propaganda tool for terrorists. Auwal explained that the terrorists’ ultimate goal is to instill fear in the public. He advocated that journalists should therefore focus on reporting stories of survival and resilience, rather than prioritizing the precise accuracy of every grim detail.

Perhaps the most thrilling aspect of KAPFEST 2.0 occurred during the combined book chat for Seeking Barhama by Ba Sabouke and Back Home There’s a Box of Chocolate by Odu Ode, moderated by the poet and scholar Dr. Ismail Bala. The session became an exuberant intellectual duel between Dr. Bala and Sabouke, who were battle-ready, trading provocative questions and equally sharp retorts to the delight of the cheerful audience. Seeking Barhama explores eromysticism, and when asked about his decision to blend mysticism with eroticism, Sabouke retorted, “Everything mystical is erotical.”

“How do you find God in erotica?” inquired Dr. Bala. Quoting Ibn Arabi, Sabouke replied, “Our love for women brings us closer to God.” He further explained, “Even the erection of the penis is an affirmation of God’s existence,” a statement that caused a stir in the audience. “The communication between God and the servant in prayer is deep,” Sabouke continued. “It’s the kind of depth achieved during intimacy, where you communicate with each other’s souls. God exists within the soul.” He concluded, “So, in the softness of a woman’s body, you reach her heart, where even God resides.”

Sabouke described poetry as the greatest tool discovered by the Sufi for seeking God. When questioned by the audience, one person asked, “Barhama said he is seeking himself. How do you seek what is seeking itself?” Sabouke responded with a quote from Rumi: “What you seek is also seeking you.” This profound exchange served as the climax to an exhilarating session, which then recessed for lunch and prayer.

The session reconvened with a panel discussion titled “Reimagining Peace and Documenting the Women’s Cost of Conflict.” This marked a direct shift from the day’s most exuberant conversation to its most emotionally charged one. Moderated by Hassana Maina, the conversation featured Ummusalma Farouq Sambo, Jacinta Egbim, and Hauwa Saleh.

Narrating her ordeal after escaping an imminent abduction by bandits, Ummusalma reflected on her struggle with trauma. She observed that the men involved in the same incident moved on with an ease that left her stunned, while she was unable to shake it off. Speaking with a calm and precise demeanor, Ummusalma concluded that women suffer the most during war. When a man interjected, “But men die in war,” she stunned the audience by replying, “In war, death is a mercy.” At that moment, I found myself silently reciting the lines from J.P. Clark’s ‘The Casualties’: The casualties are not only those who are dead; / They are well out of it.

The next event was another book chat, featuring Sophiyya Embee hosting Star Zahra to discuss her acclaimed collection, Girls and the Silhouette of Forms. Star shared her thoughts on poetry, writing, and the personal narratives that inspired the collection, which she had assembled over two years. “The essence of poetry,” she said, “is in the abstract.” By the time the conversation concluded, evening had fallen.

All three evenings of KAPFEST 2.0 possessed an unforgettable allure and energy. The second evening was slated for the Mudi Spikin Poetry Slam, for which young poets auditioned via social media. Nineteen were selected, though one ultimately failed to appear. Tobi Abiodun, Star Zahra, and Abba Musa Idris formed the panel of judges—a difficult task, given the intensely competitive field. Any of the participants could have been a plausible winner. They took to the stage with fire and ferocity, dispensing words that aimed directly at the audience’s souls. With eyes firmly on the prize, each performer was determined to be the best, a resolve clearly expressed in the powerful effectiveness of their delivery.

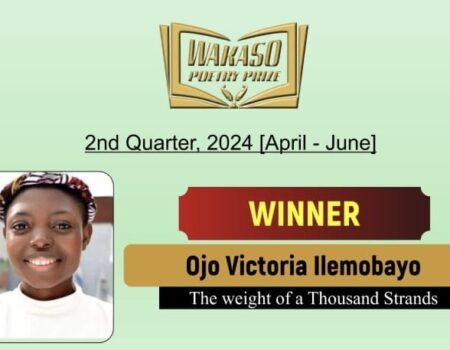

After open grading of each performance, eight poets advanced to the second round, and four progressed to the final round. A tie between the top two contestants necessitated an additional round. On this occasion, Kano, the elephant’s belly, fell short of its mantra, “whatever is your prowess, someone does better,” as Shafa’atu Muhammad Balarabe (who was misidentified as Shafa’atu Ahmad on her prize cheque) came from Kaduna to win the slam. She took home ₦500,000, while the first and second runners-up received ₦300,000 and ₦200,000, respectively. Mukhtar Mudi Spikin, a poet and textile entrepreneur for whom the slam was named (in honor of his father, a post-colonial renowned poet and politician from Kano), added a gift of fabrics for the winner and finalists. For many, the poetry slam was the highlight of the festival, signaling a bright and prosperous future for poetry in Northern Nigeria.

Perhaps the only problem with pleasure is its brevity. All too soon, we had arrived at the finale of KAPFEST 2.0 on the third day. That morning, hints of a torrential downpour gathered in the clouds, even as the sun shone through. Nana Sule engaged the audience with brief games before the erudite Professor Ibrahim Malumfashi took the stage to moderate a Hausa-language panel titled “Ink of Defiance.” Featuring Abdulaziz Abdulaziz, Sulaiman Usman Yusuf, and Jalaludin Maradun, the panel made a powerful case for the pen being mightier than the sword. Uncommon wisdom poured from the speakers, and moments later, large raindrops began to smash onto the roofs and soil of Kano.

Next was a conversation between Richard Ali and the festival’s headliner, poet Dike Chukwumerije, who is widely known for his staunch advocacy for a united Nigeria and his role as a provocateur of socially conscious art. The session felt like one of those exchanges between Tyrion Lannister and Lord Varys in HBO‘s Game of Thrones, where every question is as exciting and puzzling as its answer. By the end of the chat, the entire audience was on its feet, applauding.

The next panel, “Beyond Medicine: The Art of Healing,” was moderated by Gabe and featured Fiddausi Abba Wada, Aisha Ahmad Ibrahim, and Shuaib Sani Shuaib. This, too, was an emotionally charged conversation. Fiddausi shared her personal struggles as a therapist who deeply resonated with her clients’ plights, often finding herself drowning in their pain. She recounted how becoming a mother intensified this empathy, making it incredibly difficult whenever her child cried. “It was like a crying competition between me and my baby,” she said. Aisha and Shuaib provided further insights into how artistic works can act as a powerful catalyst for succor and healing.

After lunch and prayer break, Nana Sule moderated a panel discussion on “Building Safe Spaces Through Literary Communities”. On the panel was Simnom Emmanuel, founder of Rambling Thoughts Book Club, Kaduna; Yahuza Rabiu Garba, leader of Yobe Literary Society; and Younglan Talyoung, the poet and writer from Jos.

Afterwards, Ahmad Muhammad Ahmad moderated a panel on “Artvocacy: Championing Change Through Creativity,” featuring Sani Muhammad, Yazid Salahuddin Mika’il, and Muhammad Bayero Yayandi. The discussion centered on the compelling societal effects of humanizing data through storytelling—how stories can influence both the public and authorities. Then the king arrived, breathing renewed energy into the festival. Media presence tripled, and his attendance marked the point when cameras were most actively summoned into action. Hafsat Ismail Zubair, one of the contestants in the festival’s poetry slam, performed a poem that captivated the entire audience and, most notably, the Emir himself, eliciting nods and smiles of approval from him.

The Emir of Kano, Muhammadu Sanusi II, accompanied by courtiers and palace servants, graced the festival, bestowing upon it a distinct prestige. He was symbolically hosted by his daughter, Yusrah Sanusi, a poet, writer, editor, and accomplished moderator who has graced the stages of the Aké Festival and KABAFEST. Their discussion, titled “Unlocking Northern Nigeria’s Literacy Potential,” focused on the critical need for education. The Emir urged everyone to prioritize learning on a personal level, stating, “Anything can be gifted to you or taken away, but not education. Once you have it, no one can take it from you.”

While criticizing the state for not doing enough to finance quality education in Nigeria, the Emir suggested that places like mosques could be used as improvised learning environments, as they are only used briefly five times a day for prayers. He also lamented what he described as the “unfortunate” state of leadership in the country, stating, “You rise and fall with the quality of your leadership.”

The Emir attributed the disparity in performance at local Islamic schools (Tsangaya) between children from Borno and Kano to nutrition. He recalled a time when children from Borno, aged 10 to 13, would come to Kano and successfully memorize the Qur’an, a task that Kano children of the same age struggled with. “You don’t need to be rich to feed your children the right meals for healthy brain development,” he stated. He blamed the problem on ignorance, illustrating his point, “a farmer here will cultivate beans, sell them at the market, and then return to his village to buy bread and a coke, thinking he’s arrived.”

When asked from the audience about the controversies surrounding his name and how he is constantly misunderstood, the Emir responded by referencing his tenure as Central Bank Governor. “I had responsibilities which I delivered 100 percent,” he said. “So, I’ve earned the right to be critical of everything in Nigeria.”

Another question was asked about his journey to becoming a public intellectual, he revealed his competitive nature. “I am a highly competitive person; I don’t accept being second. When I was governing the CBN, I wanted to be the best governor in the world, and I was. When we perform a Durbar, I want the Kano Durbar to be the best. When I attend a gathering of Emirs, I want to be the best-dressed Emir in the space.” He concluded with a principle that guides him: “If you accept mediocrity, you become mediocre. I have always wanted to be the best at anything I do. If you accept average, well, good luck.”

The Emir’s chat was the undeniable climax of the festival, commanding excitement from everyone present. The two remaining sessions that followed could only play catch-up, as if the festival itself had heeded the king’s stated desire to be the best at anything he participates in. Before his departure, the Emir was escorted to a Poetry Dispensary outside the hall, manned by Hauwa Saleh, for a special exhibition.

The poet and novelist Umar Abubakar Sidi hosted a book chat with Nana Sule on her acclaimed story collection, Not So Terrible People, preceding the evening’s poetry and music performances. The night began with Dike Chukwumerije’s passionate, playful, and soul-piercing performance, the longest of the night. After him, Abdulrazaq Salihu, Abdulmajid Gambo, and others took the stage before the event transitioned to music.

Popular Kannywood singer Hairat Abdullahi opened the musical segment. Abubakar Sani evoked childhood memories for many attendees with his songs, and finally, Hadiza Maikano brought the festival to a close, ending the night in a frenzy of music.

The Kano International Poetry Festival is the biggest creative rendezvous this year in the North, and Poetic Wednesdays Initiative has curated it, following the initiative’s success in establishing the region’s first poetry festival last year. The story of Poetic Wednesdays Initiative is one of consistency, determination and sheer obsession with greatness even when the odds are stacked against this goal. What started in 2016 as a social media hashtag is now the biggest youth literary community in Northern Nigeria, organising the biggest literary festival in the region just in its 9th year. This festival is the sum of those efforts.

Singling out one moment as the most remarkable from KAPFEST 2.0 would be a subjective and debatable exercise, which is, in itself, the greatest testament to the festival’s success. For some, it was the evening at Gidan Dan Hausa; for others, the poetry slam or the chat with the Emir. Some would champion the poetry and music night, while for me, it was the book chat between Ba Sabouke and Dr. Ismail Bala.

Kano is the undisputed commercial and entertainment capital of the North, with events like KAPFEST finding its way into the heart of the city, recognizing it as the region’s cultural capital is only a matter of time.

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu is a freelance book reviewer and fiction writer based in Kano. In June 2024 he was selected for the Flame Tree Project that aimed at bringing new voices in Northern Nigerian literature, facilitated by two past winners of the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim and Chika Unigwe. He was a finalist in the book review contest of the festival books of the 26th edition of Lagos Books and Arts Festival (LABAF)

![You are currently viewing [Featured Post] KAPFEST 2.0: The Three Days of Cultural Immersion in Kano](https://jaylit.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG-20250906-WA0024-e1759510912992.webp)