The gradual defamiliarization of Aké in the lit space—from the childhood memoir of a literary sage to the annual pilgrimage that draws faithful from the nooks and crannies of the literary ummah to pay homage to African arts and literature and to deliberate on pressing issues of the Global South—began in 2013 with a perpetuity that now brings us to its thirteenth edition. Memoir or festival, both are a libation poured to celebrate Africa’s 91-year-old first Nobel laureate in literature, Wole Soyinka, and his towering legacy, with the latter curated by his daughter-in-law, the quintessential poet, novelist, and publisher, Lola Shoneyin.

Three months ago, I wrote about a literary festival in Kano, where we cockily tell strangers, “Ko da me kazo anfi ka”—whatever your prowess, someone surpasses it. Kano is exuberantly chaotic, but based on what I witnessed last year and this, even in the next life, it will never match the ferocity of Lagos chaos. Lagos is aggressive. That aggression even seeps into casual conversation, often flaring into not-so-friendly rows, though the speakers rarely mean true harm. The ethics of Lagos defy simplification. Respect and disrespect are served in equal measure.

Police in Kano are not only feared but respected and, in some cases, revered. Last year, while heading to Badagry from Mile 2, the driver and conductor of the bus I boarded combined into a seamless team, unleashing a torrent of verbal abuse on policemen around Ojo who had invited their ire. If not for the city’s tradition of prolonging verbal altercations, the row could easily have escalated into a physical clash in place like Gboko, my natal town, where arguments are settled with fists. This year, I encountered something bizarre that seems utterly normal to Lagosians: a flock of touts at Oshodi bus stop, running and collecting illegal taxes from drivers who surrendered them without resistance. Those who dared to resist risked significant damage to their vehicles from the clubs in the fists of shirtless Agberos. In Kano, I might easily be dismissed as a liar for describing this brazen, almost unimaginable daylight extortion.

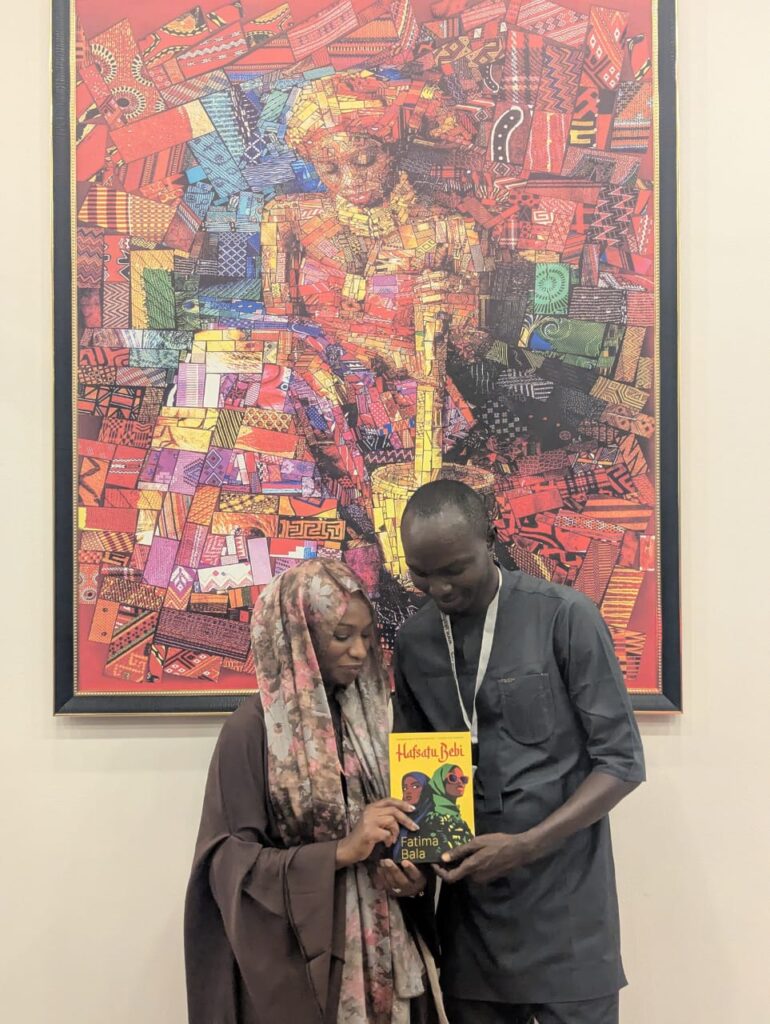

I’d missed the first two days of the festival. I woke up to a message from the novelist Fatima Bala asking if I was still coming. It was sad that I had to watch all the three fantastic sessions she had at the festival online. A heavy downpour in Apapa the previous evening kept me away on the second day, and the Lagos horizon still looked drab and mournful on Saturday morning, the final day of the 2025 Aké Festival. Had the forecast not promised otherwise, the sky seemed ready to weep. The day’s first event, and perhaps the most anticipated program of the festival, was an interview with Bernardine Evaristo. Passing through Airways, Costain, and onward to Ikeja, I made sure to arrive a full hour early. And unlike the city’s weather, the atmosphere at the BON Hotel was radiant and dazzling. In the spacious hotel reception, I was greeted by smiling faces in beautiful outfits. At Aké, it seems, everyone is sartorially aware.

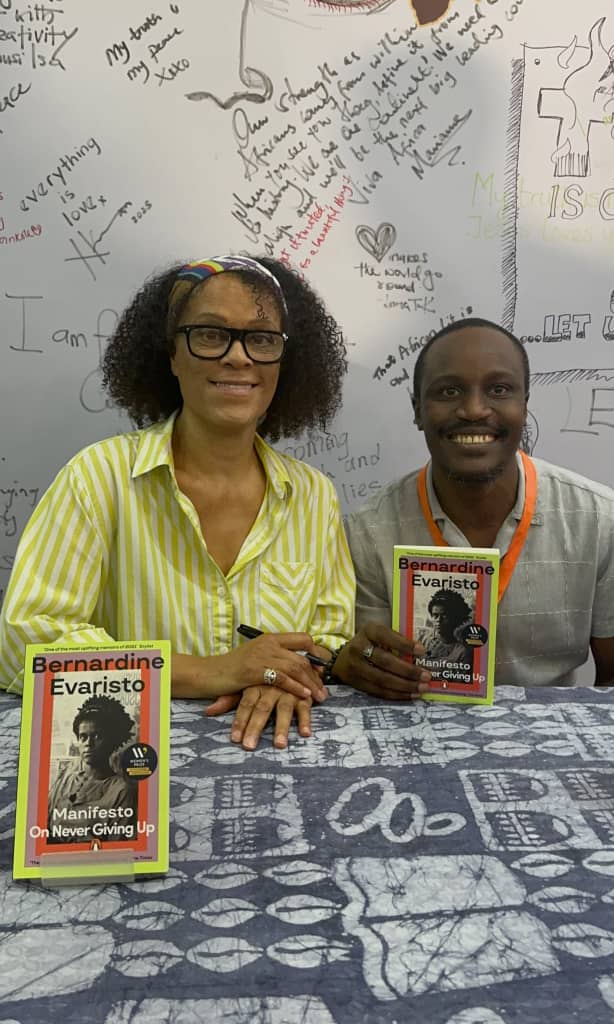

After six years of mentioning Bernardine Evaristo’s name for a trophy-parade—as one of only two writers of Nigerian origin to have won the Booker Prize—I finally sat before her and watched her discuss her memoir, Manifesto on Never Giving Up, hailed by The Times as “the perfect read for everyone who dreams big.”

The moderator, Angela Wachuku, was also a guest at Aké last year, but I’d missed her panel—a night session—and with it, the chance to be au fait with her. Now, after witnessing her superb engagement with Evaristo, I don’t think I’ll ever forget her. O boy, she is such a brilliant host! On paper, her surname reads Igbo, but her accent and forehead point to Kenya. A glance at her biography in the Aké Review confirmed the latter. Last year, it was Wanjiru Koinange who commanded my admiration; this year, it is Angela Wachuku. Kenyans have long held a respected seat at the table of African literature—a country that has given us Khadija Abdalla Bajaber, Grace Ogot, Binyavanga Wainaina, and the great Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

Throughout the book chat, Bernardine Evaristo exuded grace and a kind of motherly authority, guiding the young audience through important lessons drawn from her life and creativity. She drew on personal experiences—a strict and fiercely protective father, leaving home at 18, and the long-awaited reward for years of labour that finally arrived with her Booker win. On page 68 of her memoir, she describes her teenage self as “not pretty.” But as the saying goes, so much water has passed under the bridge; I believe everyone there would agree that we met a truly beautiful 66-year-old woman that morning.

Speaking from the audience, the poet Dami Ajayi thanked Evaristo for serving on the judging panel that shortlisted his work for an international prize six years ago, an event he described as “life-changing” and a gateway to the opportunities he enjoys today. Perhaps emboldened by the maternal tone she had woven throughout the session, he then sought her advice: How could he mend the rift between himself and his friends in the writing community, brothers turned rivals? She resonated with his situation and encouraged him to be the one to extend friendship, to reach out generously. In this age of social media, she concluded, you can bridge divides simply by sharing a friend’s book or offering public praise. A few more thoughtful questions followed before this exhilarating conversation between the literary powerhouse Bernardine Evaristo and the supremely capable moderator Angela Wachuku drew to a close.

Ahead of his panel, the Canadian journo-scholar Adrian Harewood had been tweeting about his exhilarating Aké experience. Now, he took the stage alongside Congolese investigative journalist Jonas Kiriko and the Indian British writer Sonia Faleiro, in a session hosted by the Kaduna polymath Joseph Ike, to discuss the vital but provocative topic of “Global Media and Selective Empathy.”

The panel interrogated the culture of sidelining the Global South in mainstream media coverage. The host opened with a startling statistic: a single civilian death in a geopolitically powerful nation generates an average of 870 news articles, while deaths in weaker nations, particularly in Africa, receive negligible attention. To illustrate the starkness of this empathy gap, he asked the audience to guess the comparative figure. No one came close to the answer: 18 articles. The conversation centered on this profound imbalance—the systemic lack of attention paid to the suffering and struggles of the world’s most disadvantaged nations.

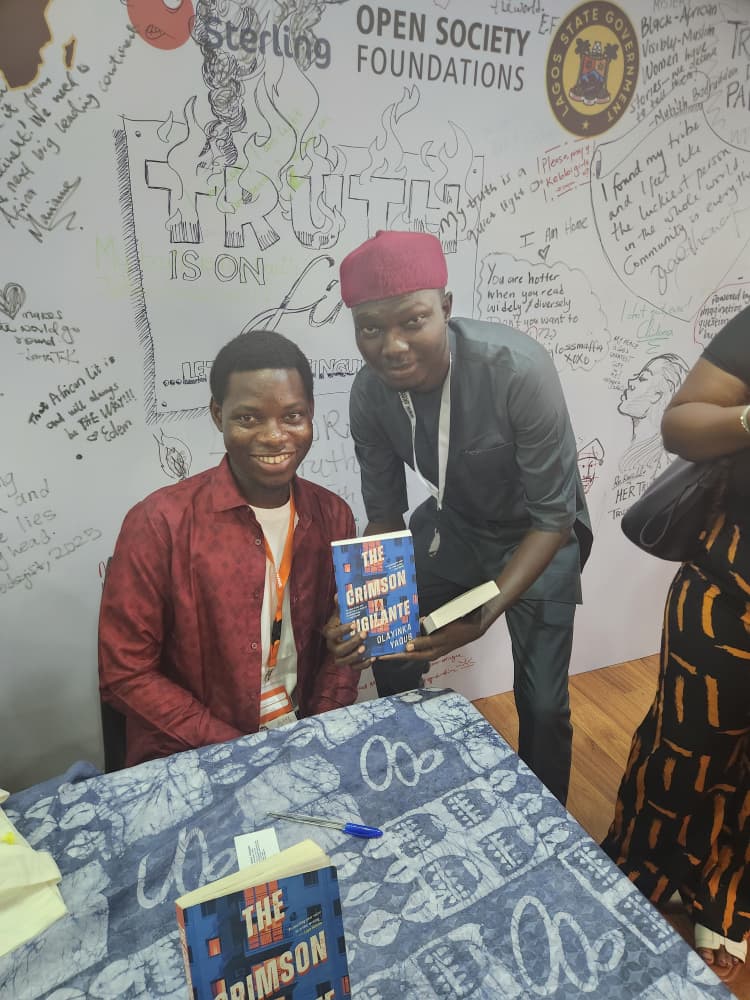

The next program brought a moment of personal pride. It featured a combined book chat on Olayinka Yaqub’s The Crimson Vigilante and Femi Kayode’s Gaslight—two crime thrillers dazzling their way into the hearts of Lagos’s reading community, hosted by Chinenye Igbudu. In “A love Note to Lola Shoneyin”, I described the Aké Festival as a platform where new voices are incubated, amplified, and catapulted to prominence. Olayinka and I attended last year as mere attendees, the bottom rung of the participant hierarchy. Back then, he told us about his forthcoming book. This year, he returned as a guest, at the very top of that ladder, while I, too, moved up a step by attending as a member of the press.

The combined book chat filled the hall to the brim; many had to stand, and the audience followed the conversation on stage with palpable energy. It was no wonder, then, that The Crimson Vigilante had sold out even before the event began. There is a generational gap between Kayode and Yaqub, and Chinenye Igbudu, spotting this, asked the former to advise the latter on how to keep soaring. “Generosity,” answered Kayode, “is the most important thing that will keep you going.” Impressed by Yaqub’s outing on stage, the distinguished Nigerian writer and artist Abdulkareem Baba Aminu declared himself a fan and offered words of encouragement to the “Star Boy” of the festival.

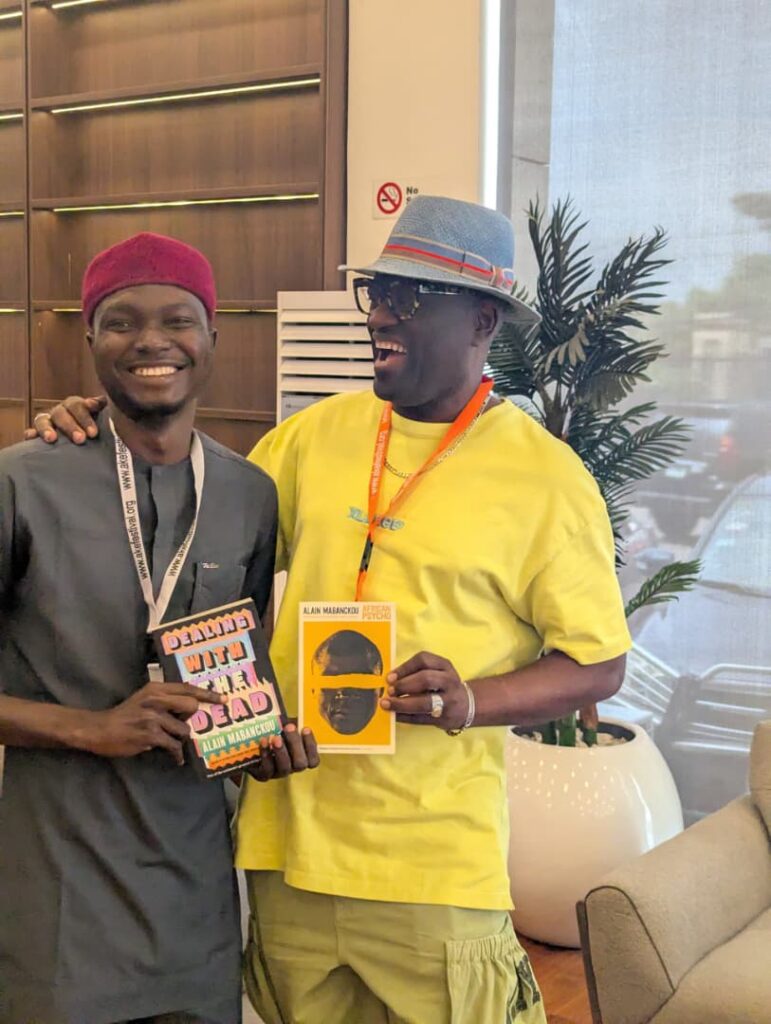

Alain Mabanckou was one of the literary stars who graced the festival. I met him at a reception during a lunch break, and what my encounter revealed is that he lives like a star in every sense of the word. To describe his personality to a football fan, I would say he is enigmatic like Zlatan, boisterous like Cristiano, yet as humble as Ngolo Kanté. He carries himself with panache and dresses impeccably, yet remains a completely street-happy man. Three days after his home country, the Congo, triumphed over Nigeria in the World Cup play-offs, Mabanckou announced his arrival In Lagos with characteristic humor. On social media, he posted a picture of a meal he was enjoying, joking that Nigerians bore no grudge—because we were feeding him so well. In another post, he shared a lighthearted chat with a young Nigerian at the festival who told him her favorite Congolese musician was Awilo Longomba.

Interestingly, Mabanckou released his debut novel in 1998, the same year Awilo Longomba’s album Coupe Bibamba hit the airwaves. A line from one of its hit songs, “Comment tu t’appelles? Je m’appelle Coupe Coupe Bibamba!” became more popular on the lips of Nigerians than the national anthem. When I began learning French in secondary school in 2004, I was thrilled to finally understand what those catchy words meant: “What is your name? My name is Coupe Coupe Bibamba!”

The album was so influential that the legendary Hausa comedian Rabilu Musa Ibro portrayed Awilo in a film, performing Hausa-language versions of songs from the album. This was no small feat, given that such acceptance came from one of Nigeria’s most conservative and culturally steadfast regions. The last time I remember a Congolese song capturing Nigeria’s attention was about two years ago, when Afara Tsena’s Afro Mbokalisation trended on Reels and TikTok.

Mabanckou was also excited by another aspect of the festival, evident from his social media posts: the overwhelmingly youthful audience, which suggested a promising future for African literature. He was not the only guest struck by this. Bernardine Evaristo expressed similar enthusiasm in an Instagram post. Well, this is hardly surprising. Nigeria is a nation of young people, with more than 70 percent of its population under the age of 30.

Appearing on stage for the second time, Palestinian author Adania Shibli was joined by veteran Nigerian journalist Kunle Ajibade, in a conversation hosted by Dr. Olaokun Soyinka. They explored the festival’s theme, “Reclaiming Truth”—rephrased for the panel as What is Truth? Shibli’s presence brought a sense of relief, especially after last year’s experience, when her patriot, the poet Najwan Darwish, announced for the main theme panel “Finding Freedom”, was unable to attend due to travel restrictions imposed by the Israeli government. This time, a Palestinian voice was on the Aké stage, able to share the Palestinian story directly.

Dr. Soyinka opened the panel by asking Ajibade about his experiences with persecution for telling the truth. Ajibade recounted his ordeal under the Abacha regime, drawing from his own memoir. Shibli then shared her own struggles with Israeli authorities, including a pointed anecdote about her sister mediating a tense encounter with the police by softening her mother’s words to the authorities who didn’t understand Arabic and their harsh words to her mother who didn’t understand Hebrew. Later, an audience member raised a difficult question: What kind of truth should we tell? They recalled once speaking a truth that inadvertently led to someone’s death. So which truth do we choose?

In response, Shibli suggested that impact should sometimes take priority over stark fact—especially when the plain truth could cause harm. This, she noted, is where ethics enter the conversation. In Arabic, she reminded the audience, both literature and ethics are known as adab. Some truths, while factual, may be unethical to voice; the focus, therefore, should remain on what is ethical.

The festival’s final panel, “Mainstream Media and the Loss of Trust,” was preceded by a joint book chat hosted by Thande Abigail, which featured Louisa Onome’s Pride and Joy and Olufemi Terry’s Wilderness of Mirror. Moderated by former BBC journalist and self-described “accidental diplomat” Fatima Zahra Umar, the panel brought together writer and former presidential aide Tolu Ogunlesi, French author and journalist Colombe Schneck, and Ukrainian writer and war documentarian Myroslav Laiuk.

Their conversation examined the narratives shaped by traditional media, the public’s perception of them, and the ways in which the internet and social media have democratized information and the consequences of this new liberty. Ogunlesi emphasized a shared duty to counter misinformation, while recognizing the challenge of shifting entrenched beliefs. “People can believe whatever they want,” he concluded pointedly, “but beliefs have consequences.” As an example, he pointed to vaccine hesitancy, noting that those who refuse vaccines ultimately bear the risk of infection themselves.

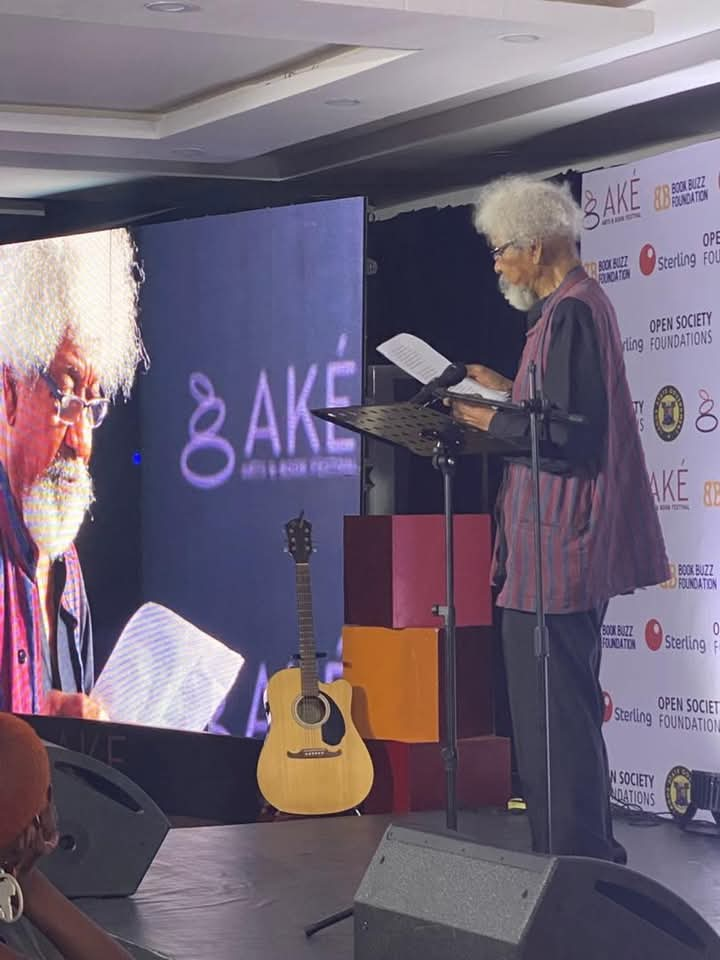

When the Poetry and Palm Wine Night arrived, the entrance of the Nobel Laureate became the crowning moment of the much-anticipated evening. Seated between his son and Booker Prize winner Bernardine Evaristo, Wole Soyinka became the silent, magnetic center of the room, as both overt and discreet cameras turned toward him. True to tradition, the night began by honoring the hands and minds behind the event’s success. The team, guests, volunteers, and attendees were each celebrated with music and dance.

A little-known poet named Ocheka (hopefully I have his name right) opened the evening’s performance with an electric delivery, reciting a poem on the difficulty of moving on from love. Festival director Lola Shoneyin said she had only recently discovered him and had promised then to bring him to Aké. Turning to him, she added warmly, “So proud of you—I’m glad I kept my promise.”

Next, Dami Ajayi was introduced by Lola as someone who “writes about women in a very special way.” Before reading, he took a moment to acknowledge Lola’s “pivotal” role in his career. He then clarified that the poem he would perform was not, in fact, about women. I don’t recall its title, but I remember it as socially conscious, woven through with medical metaphors.

My highlight of the evening came when Lola announced a brief “trip to Northern Nigeria” and introduced Zaynab Iliasu Bobi, the rave of the moment in experimental poetry. To put it mildly, her performance at last year’s Aké had been lackluster, prompting Lola to offer her some advice on vocal projection. This time? What a massive evolution. She owned the stage with a sagacity that finally matched her talent on the page. In a chit-chat after her performance, she told me that Bernardine Evaristo had requested signed copies of her two books. The day Bobi and I spoke first, Umar Abubakar Sidi introduced her to me as “the future.” While I agree with him, I would also argue that she is very much the present. That evening, she breathed life into poems that penetrated the soul of her audience. It was a memorable performance.

The Somali poet Momtaza Mehri took the stage after Zaynab. A few hours earlier, I had accidentally bumped her with my elbow at the venue’s reception. I felt terrible, but couldn’t help smiling when she gently waved off my apology. Such a gracious lady. Momtaza read two poems from her prize-winning collection, Bad Diaspora Poems. The first began with the remarkable line, “love is a western union transfer,” interrogating the pressures faced by diasporans to send remittances back home. The evening had its first music performance from the multidisciplinary artist Victor Adewale, including his song “Adetokunbo,” which celebrates Africans living abroad.

Afterwards, Jamaican poet Yashika Graham graced the stage. I’ve never fully understood the emotional weight of the diaspora, but Yashika’s teary eyes—moved by Adewale’s song on the subject—explained it to me more powerfully than words ever could. She shared that she is the first in her family to return to the African continent. As she spoke, her words seemed to carry me across the Atlantic, to the stories of the Door of No Return. After her performance, Lola assured her, “This won’t be your last time in Lagos.”

All the way from Portsmouth, Bash Amuneni took the stage, accompanied by Mide Fash on guitar. After a few words on diaspora and homecoming, Bash performed his poem “We Have Come Home to Reclaim the Truth,” and then the banger, “There Is a Lunatic in Every Town.”

Next, Lagos-born, Canada-based poet Chukky Ibe delivered an electrifying performance centered on the beautiful madness of Lagos, a city he “hates to love” yet will always call home, will always call father, for its “beautiful, beautiful chaos”. His second poem, whose title I cannot recall, was playful and engaging, holding the audience spellbound. He earned thunderous applause after closing with the line: “I don’t change pampers. I pamper!”

And then, ahem, Lola introduced her father-in-law, and the entire Aké audience rose to applaud and cheer. To witness the 91-year-old Wole Soyinka perform a poem live was a moment I never anticipated. Surreal, yet profoundly real. The poem was a tribute to Che Guevara, marking the revolutionary’s posthumous 100th birthday.

The master of disguises, Umar Abubakar Sidi, disguising this time as a soldier-poet took the stage after the sage. Though in mufti, he began with a formal military salute to the Nobel laureate. He then performed the eroto-mystical poem, “The Veiled Secrets of the Kamasutra,” which held the Aké crowd in rapt attention, drawing nods and smiles even from Baba Soyinka himself by its conclusion.

The final poet to grace the stage was Wana Udobang, who came with a bang. Her first poem addressed the plight of children in Gaza. This was followed by a piece on crashing out and closed with a goodbye poem, “go and come back,” bidding tasleem to the Aké congregants. All the three poems from her were deeply emotional, yet she delivered them with a playful, engaging tone that joyfully captivated the crowd. After her performance, in Lola’s words, “All that is left now is The Recurrence.” The festival closed with the vibrant fusion of rock and Afrobeat from the musical group, bringing the night to an end in song and dance.

Poetry is a nourishing feast for the soul, and this evening was, by far, the most remarkable poetry and music night I have ever witnessed at a literary festival. To have the privilege of seeing Kongi himself perform on stage was an unforgettable highlight. This session was the perfect culmination of the event, a memory that will truly endure.

Before the Poetry and Palm Wine Night, I asked Salim Yunusa, founder of the Poetic Wednesdays Initiative and co-curator of the Kano International Poetry Festival (KAPFEST), which he enjoyed more: the fantastic program or the inspiring people we met. He chose the latter. That’s when I realized that my own most cherished moment came when Lola Shoneyin first spotted me taking photos with friends. She welcomed me with such warmth, a hug, and a sense of familiarity that truly took me by surprise. It was a priceless, unforgettable instant. See you at Aké 2026!

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu is a freelance book reviewer and fiction writer based in Kano. In June 2024 he was selected for the Flame Tree Project that aimed at bringing new voices in Northern Nigerian literature, facilitated by two past winners of the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim and Chika Unigwe. He was a finalist in the book review contest of the festival books of the 26th edition of Lagos Books and Arts Festival (LABAF)

![You are currently viewing [Featured Post] Aké 2025: Thirteen and Counting](https://jaylit.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/PHOTO-2025-12-23-01-39-53.jpg)