Introduction

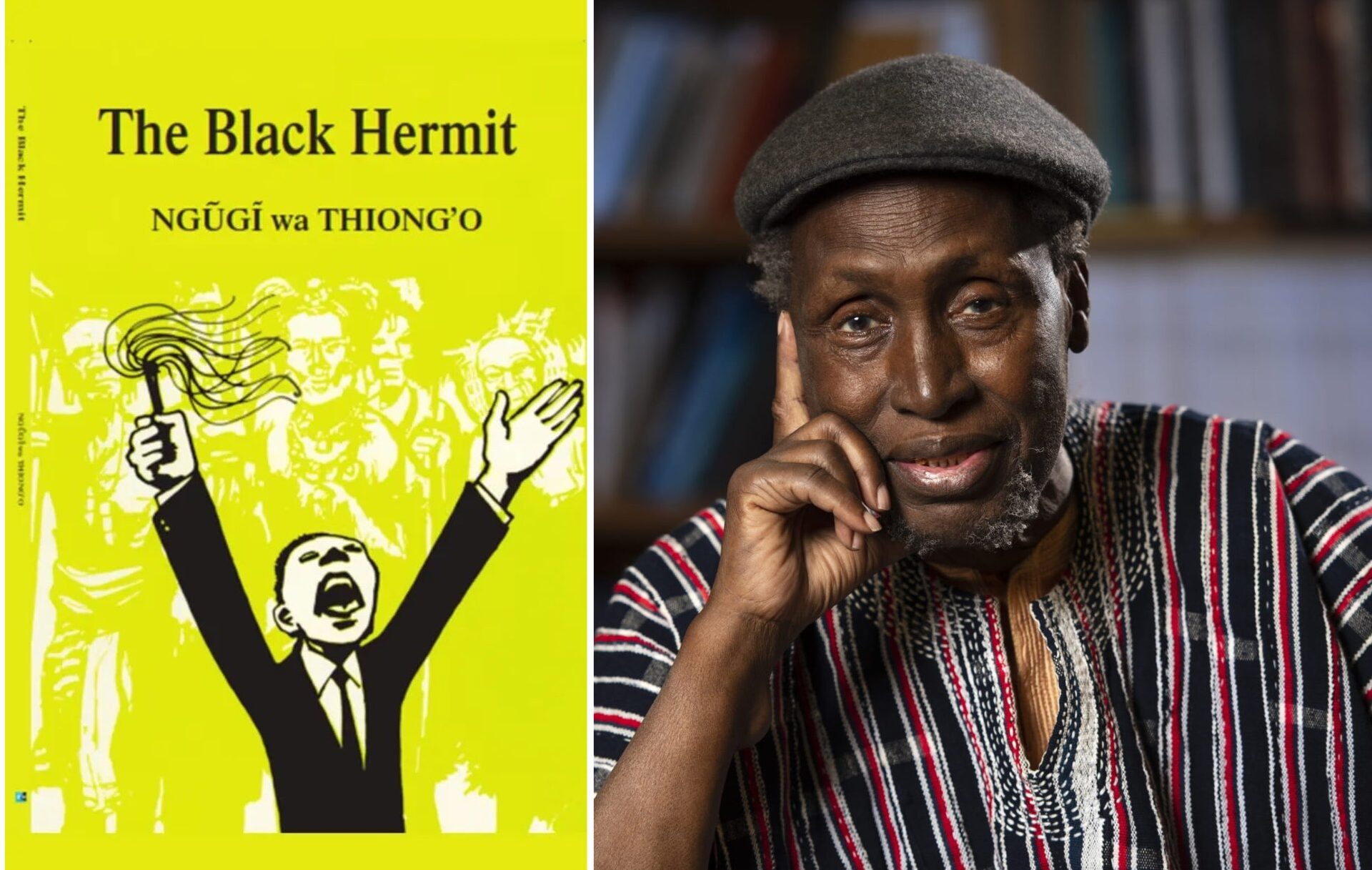

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has cemented his place among the legends of African Nationalism as seen in his literary contributions across the three genres. His critique is both external and internal. In his 1962 play The Black Hermit, first performed at the famous Makerere University at a critical time – the independence of Uganda and the eve of Kenya’s – we meet his critique of identity and displacement. If the timing of the work says anything then it is that it serves two functions: celebrating the liberation that the black race has achieved and giving caution to pseudo-colonisation. This offers a grounding for exploring the psychological implication of decolonisation. In the lead character, Remi, who returns to his native place after intellectual sojourn in the city, the playwright frames Frantz Fanon might call a “clinical study” (200) of what alienation is in the light of postcolonial experience. Kenya’s experience becomes a mirror to what was pervasive in the African nations then being liberated, the problem being that of returned native who discovers himself homeless in his homeland. Using the identity conflict portrayed in Remi, with its inability to mingle with his people upon return juxtaposed with inability to fit it to the urbane lifestyle and ideology, this essay argues that it reflects the struggle of the postcolonial African nations, particularly Kenya, in reconciling indigenous vitality with received colonial idealism. In Remi’s psychological exile we see what Edward Said, writing in Reflections on Exile, termed a “metaphor for our age” (174), as it deals with the issue of belongingness. The essay approaches Remi’s failed homecoming through Fanonian psychoanalysis and Bhabha’s theories of hybridity, in this way it uncovers Ngũgĩ’s warning about the dangers of uprooting cultures in newformed nation-states.

Historical and Political Context

Reading The Black Hermit within the context of what historians call Kenya’s “second colonisation”—that era immediately following independence when Western-educated elites simply replaced British administrators without transforming oppressive systems, brings out its significance. Ngũgĩ wrote the play while at Makerere University, an institution that, as Carol Sicherman notes, “produced the very class that would perpetuate colonial structures” (87). It is this sad paradox that gives life to Remi’s character in the play. The villagers’ desperate plea “Lead us against Uhuru’s government!” (Act 1, Scene 2), speaks volume of the bitter irony that marked disillusionment in the postcolonial period. The average villager did believe that Remi’s Western education qualifies him for leadership; this itself is nothing but an uncritical glorification of colonial credentials. Upon the return of Remi, they reject his vision of anti-tribal modernisation by saying “No” to his “Build schools, not tribes!” (Act 3), as if to demonstrate the contradictions Fanon prophesied when cautioning that “the national bourgeoisie will be quite content to take over from the Europeans” (122). Ngũgĩ heightens this tension through linguistic juxtaposition. A Remi that is fluent in Queen’s English and stuttering in his native Gikuyu is all that Ngũgĩ needs to demonstrate as “colonial alienation” (17), that split in the psychic when education displaces Africans from their language. Another reference in the play to this can be seen in the pastor’s accusation: “You trust books over the Bible!”, an implication of the battle of ideology between colonial modernity (represented by Remi’s university degree) and Christianised traditionalism.

The Concept of Return and Exile

Remi’s experience tells us that homecoming is not that simple a thing. His physical return to Marua village may have fulfilled the elders’ prophecy about “the green plant’s return” (Act 1, Scene 2); yet psychologically, he is fixed at the point of what Said calls “the stranger who cannot belong” (181). Ngũgĩ represents this disconnect through evocative theatrical contrasts: the villagers’ dancing as a community versus Remi’s quiet soliloquies; their rhythmic call-and-response patterns versus his disjointed intellectual rhetoric. The Black Hermit leads us to rethink exile not as simply geographical dislocation but as what Bhabha designates as “unhomeliness” (9), that deep alienation from one’s cultural memory. Remi’s declaration—“I will not be led by woman, priest, or tribe” (Act 3, Scene 1), speaks of his rejecting every traditional anchors of identity. His subsequent breakdown when Thoni commits suicide reveals the existential cost of this being lost, being uprooted, typifying Fanon’s warning that “to be colonised is to be removed from history” (206). Ngũgĩ gives voice by way of this symbolic representation. When villagers perform their “old war songs” (Act 3), Remi is frozen at the periphery, he is depicted in Western suit which is seen clashing with their clothes made of animal-skin. Call it tableau vivant for it captures what Gikandi calls “the tragedy of the modern African subject” (134), suspended between worlds.

Western Education and Internal Conflict

Remi’s university education exemplifies what Ngũgĩ later denounced as “cultural bombing” (3), being as it were a systematic decimation of indigenous knowledge frameworks. His transformation plays out in three destructive ways. In the first place, language alienation: Remi’s speeches shift from communal proverbs in early scenes to abstractions that are individualistic after his return, take for example “A man’s public life needs private stability” (Act 2, Scene 2). This is a reflection of Ngũgĩ’s argument that colonial education “annihilates the colonised’s belief in their language” (9). Secondly, sexual dislocation: his involvement with Jane, the white girlfriend, concretises what Fanon called “lactification” in Black Skin, White Masks (41), the black man eroticising whiteness. Their café meetings (Act 2) is markedly different from his wife Thoni’s hearth-centered domesticity, making a space of the conflict between colonial modernity and traditional values. Thirdly, political impotence: though Remi joins the Africanist Party, his activism lacks roots. As Elder observes: “Your book-smarts won’t till our fields” (Act 3). This confirms Memmi’s position that the colonised intellectual often becomes “a stranger to his people” (120). The most impressive manifestation occurs when Remi attempts to mediate a tribal dispute. His academic rhetoric “Let us apply democratic principles…” (Act 3), ends in silence as elders override him with proverbs. This scene activates Cabral’s warning that “liberation requires re-Africanisation” (143)—a lesson Remi learns too late. Using structural contrasts, Ngũgĩ proceeds to critique education’s alienating effects. Village scenes feature call-and-response dialogue and communal decision-making, while urban sequences showcase Remi’s fractured monologues. This formal dichotomy mirrors what Irele calls “the crisis of consciousness” (89) in postcolonial literature.

Thoni as Symbol of the Homeland

The character of Thoni, Remi’s wife, models Nnaemeka’s “nego-feminism” (363), an African feminist paradigm emphasising negotiation, no ego, and compromise over confrontation. Her patient endurance (waiting years for Remi, preserving domestic rituals), differs manifestly from Jane’s commercialised sexuality. Thoni’s suicide is the play’s catalytic tragedy. Her breathless body becomes what Spivak might call “the subaltern’s final text” (104), it quietly indicts the failures of the elite’s nationalism. Take cognisance of the symbolic resonance: her death by drowning in the village stream (Act 3), overturns the traditional link of water with life, signifying the poisoning of cultural wells. In her wrapped corpse we see correlation with the bundle of traditional medicine—both rejected by Remi until too late. These two tell of his rejection of home. Her final letter (“I die waiting for your return”), echoes Fanon’s lament about “the women we leave behind” (209); homeland is feminine, hence, the home we leave behind. With Nyobi’s lamentation over Thoni’s body: “She was our bridge” (Act 3), we reach the crystallisation of Ngũgĩ’s thesis: educated elites’ rejection of traditional women like Thoni severes their connection to cultural continuity. As Nnaemeka observes, “African feminism locates agency in women’s cultural resilience” (372), a resilience Remi tragically undervalues, only to learn a little too late.

Broader Societal Symbolism

Ngũgĩ constructs Kenya’s ideological battleground through competing choruses: the elders’ tribal chants representing precolonial communalism, the pastor’s hymns symbolising Christianised modernity, and urban activists’ Marxist rhetoric embodying secular nationalism. Remi’s failure to synthesise these voices reflects Kenya’s post-independence paralysis. His ultimate pledge to “crush tribalism” (Act 3), rings hollow because, as Gikandi notes, “he lacks the cultural vocabulary to transform criticism into reconstruction” (147). This relives Cabral’s caution that “liberation requires cultural revival” (1979:143). The play’s closing scene is devastating in its ambiguity. As villagers resume dancing, Remi kneels over Thoni’s dead body, a graphical depiction of what Said calls “the irreconcilability of exile and return” (184). The continuing celebration points to what Ngũgĩ would subsequently name “the moving center” (1998), that is, society’s ability to be reborn inspite of the failures of its elite.

Conclusion

It is over sixty years after its premiere on the immortal stage of Makerere University, The Black Hermit remains alive because of how tragically prescient it is. Remi’s troubled homecoming presupposes Kenya’s recurring struggles with governance, ethnicity, and cultural identity. His tragedy, as we have seen, stems from what Fanon diagnosed as “the colonized intellectual’s deracination” (178), that is, the sharp break between Western education and cultural rootedness. Be as it may, Ngũgĩ shares optimism, that bears hope, through structural symbolism. One can see in the villagers’ enduring rituals, their dances continuing after Remi’s breakdown, “the resilience of African civil society” as put by Appiah (173). The play is therefore an argument for “re-membering”, the literal putting-back-together of severed cultural limbs, but also the psychological return to being part of one’s root. For us readers today, The Black Hermit should maintain a dual function of mirror and compass: reflecting postcolonial Africa’s ongoing identity crises while pointing toward synthesis. What must remain as lesson and have cross generational resonance is this: that devoid of cultural continuity, as Remi learnt the hard way, whatever modernity we take up is but a hermit’s existence – solitary, unsustainable, and ultimately tragic.

Works Cited

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture. Oxford University Press, 1992.

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. Routledge, 1994.

Cabral, Amílcar. Unity and Struggle: Speeches and Writings. Translated by Michael Wolfers, Monthly Review Press, 1979.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann, Grove Press, 1967.

—. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Constance Farrington, Grove Press, 1961.

Gikandi, Simon. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Irele, Abiola. The African Imagination: Literature in Africa and the Black Diaspora. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Memmi, Albert. The Colonizer and the Colonized. Beacon Press, 1965.

Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ wa. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. James Currey, 1986.

—. Penpoints, Gunpoints, and Dreams: Towards a Critical Theory of the Arts and the State in Africa. Clarendon Press, 1998.

—. The Black Hermit. East African Publishing House, 1968.

Nnaemeka, Obioma. “Nego-Feminism: Theorizing, Practicing, and Pruning Africa’s Way.” Signs, vol. 29, no. 2, 2004, pp. 357–385.

Said, Edward W. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. Harvard University Press, 2000.

Sicherman, Carol. Becoming an African University: Makerere 1922–2000. Fountain Publishers, 2005.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty.“Can the Subaltern Speak?” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, Macmillan, 1988, pp. 66–111.

Raphael Onyejizu

Raphael Chukwuemeka Onyejizu holds a Master of Arts in Literature, a Postgraduate Diploma in Education, and a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and Literary Studies. He attended Nnamdi Azikiwe University, and Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University. His articles have been featured in local and international journals, while his creative works have appeared in Okike, The Muse, African Literature Today, Nigerian Journal of Poems and Short Stories, The Criterion and elsewhere. He is a member of the English Scholars’ Association of Nigeria (ESAN), the Literary Society of Nigeria (LSN), the Literary Scholars’ Association (LSA) and the Postcolonial Studies Association (PSA).