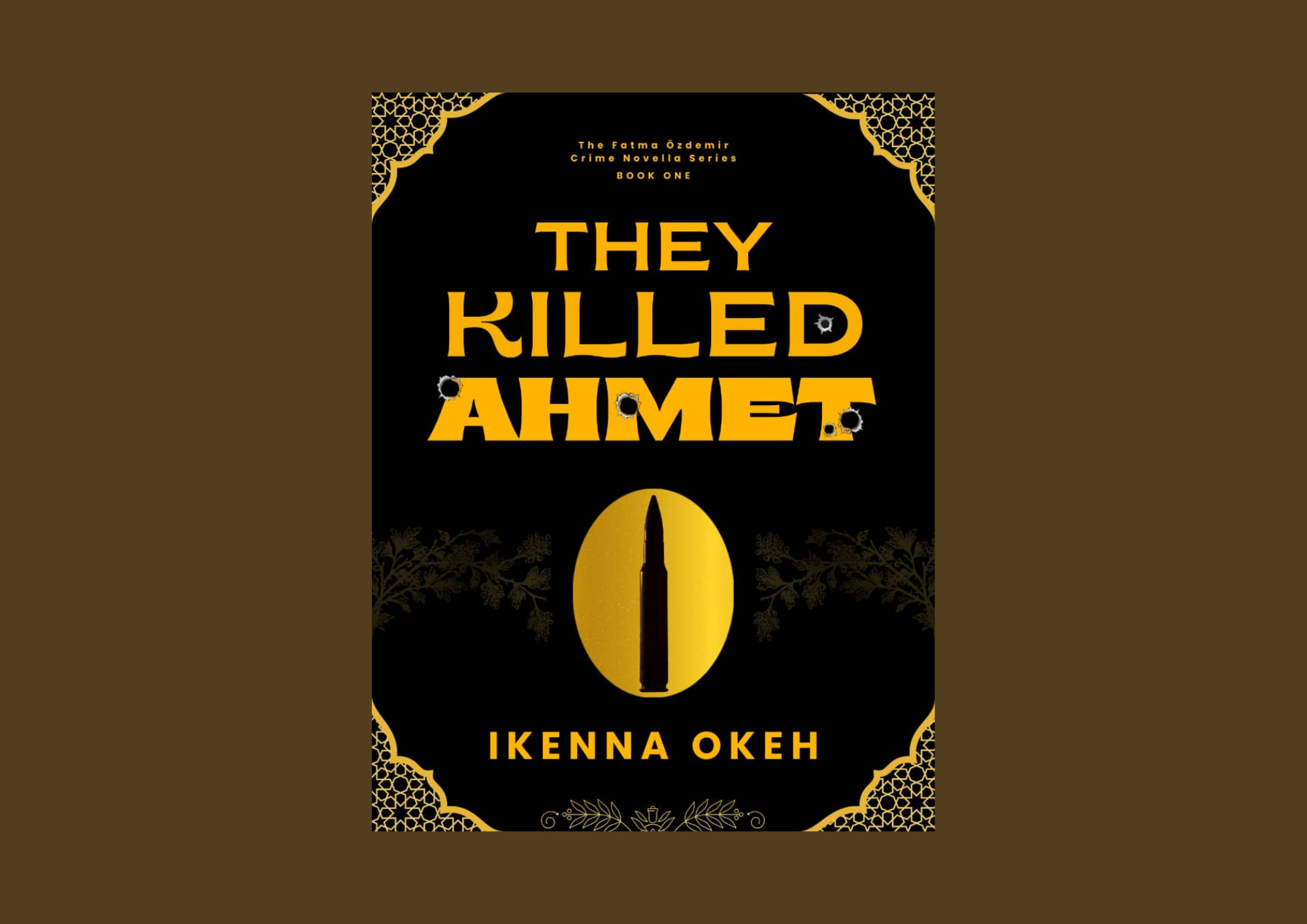

In his essay “Natives on the Boat,” Teju Cole recalls Nobel Laureate V.S. Naipaul expressing disappointment that Chinua Achebe never wrote about his decades in America. Ikennah Okeh’s crime thriller, They Killed Ahmet, departs from this “disappointment” by being set in Istanbul—the capital of Türkiye, a country where Okeh has lived.

Written with a straightforward style against a nuanced prose, They Killed Ahmet follows the young career of Police Officer Fatma Özdemir. Fresh from the academy at thirty-five, she is unexpectedly assigned as the lead detective on a homicide case where the prime suspect is still at large. Okeh’s narrative introduces us to a Türkiye where institutional sexism is rampant; a corrupt police force has likely assigned this high-profile case to an inexperienced female officer in a calculated scheme to let it fail and sweep the murder under the carpet.

The prime suspect is Huseyin, accused of murdering his girlfriend. Yet powerful, unseen forces are shielding him from investigation. This ignites in Fatma a suspicion that there is a conspiracy far more damning than the murder itself. On this foundation, the stage is set for They Killed Ahmet.

The protagonist consistently stays ahead of her unknown antagonist, who is largely relegated to playing catch-up. While Fatma Özdemir has faced significant challenges—including a suspension from work and a brutal attack—the ease with which she overcomes them can make her adversaries seem ineffective. Personally, I prefer formidable villains who present a nearly insurmountable threat, as they create greater tension and narrative engagement. I hope future installments in the series will introduce a more vicious and compelling antagonist.

While the story shows a lot of promise, it is hampered by insufficient narrative tension. Fatma is presented as a curious investigator, but the plot rarely challenges her; she is almost always correct in her suspicions. This undermines the intellectual engagement of her curiosity, making her discoveries feel unearned. However, given the story’s brisk pacing, this flaw is somewhat mitigated.

When a woman is murdered and the prime suspect is a man, readers expect the lead female detective to pursue the case passionately. In this story, however, Fatma’s every move is systematically frustrated. She turns to her ex-boyfriend, Collins Kaduna, a Nigerian man living in Istanbul, who indulges her. This alliance marks a significant shift, transforming Fatma into a police officer willing to break the law to catch lawbreakers. Collins is merely the first in a series of non-state actors she will enlist to beat the odds against a system that seems to be systematically shielding the criminals.

The author’s attempt to twist this murder mystery into a plot about money laundering and a fake mint, challenged by a patriotic policewoman eager to save her country’s economy from a potential ruin, is not tremendously successful. This ambitious pivot is undermined by clunky transitions that often depend on well-worn devices, such as secretly breaking into a forbidden location, rather than more original and careful plotting.

Fatma’s ordeals raise a compelling question: can crime truly thrive without the complicity of the authorities? While an invisible hand within the Istanbul police seems to be shielding the investigation into Huseyin’s girlfriend murder, Okeh has yet to confirm this, leaving it to seem like a series of coincidences. This brings to mind Kemi Adetiba’s blockbuster, To Kill a Monkey, the most recent crime art that I interacted with, which argues that crime can only flourish where authorities are directly or indirectly complicit. If this principle holds, the subsequent books in the Fatma Özdemir series may well open a can of worms that would expose a vast conspiracy.

One aspect of this work I appreciate is its representation of Istanbul as a truly cosmopolitan city, from its hilly neighborhoods to its diverse populace. The narrative vividly brings to life the Iranians, Russians, Africans, and Uzbeks—including their crime syndicates—as well as the city’s varied sex workers, among many other facets. Furthermore, Okeh alludes to a crucial point that Europeans seem never to learn: Africa is not a country. To them, every Black person is simply “African,” a generalization the novel effectively challenges.

As catchy as it is, the book’s title gives away the plot’s most surprising development: the assassination of Ahmet, Fatma’s partner in the homicide investigation, who is killed just inches away from her. Suspense and unpredictability are the oxygen of a fast-paced thriller, and the title undermines this by foretelling readers that Ahmet’s murder is only a matter of time.

Nevertheless, the fast-paced and accessible nature of Ikenna Okeh’s They Killed Ahmet makes it a relevant and valuable intervention in the effort to save reading culture in this era of screen addiction. The novel’s propulsive plot and straightforward prose create an experience that is intractably easy to digest, offering a perfect gateway back into the habit of reading for those overwhelmed by the demands of longer or more complex texts. It stands as a compelling reminder that sometimes, the book that saves a reader is not the most profound, but simply the one they cannot put down.

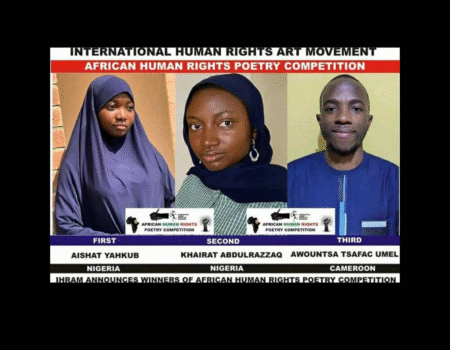

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu is a freelance book reviewer and fiction writer based in Kano. In June 2024 he was selected for the Flame Tree Project that aimed at bringing new voices in Northern Nigerian literature, facilitated by two past winners of the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim and Chika Unigwe. He was a finalist in the book review contest of the festival books of the 26th edition of Lagos Books and Arts Festival (LABAF)