Selali Fiamanya’s debut novel, Before We Hit the Ground, is a tender and affecting story of love, grief, duty and self-actualisation. It begins in the wake of Elom’s death, where we meet his parents Abena and Kodzo and sister Dzifa in mourning for him. Then we’re invited into the family’s past. In chapters spanning decades, Selali weaves threads through vital moments in the characters’ lives, until we arrive back at the tragedy. This time, with a fresh perspective, coloured by compassion which Selali has cultivated through a gentle unveiling of the family’s vulnerabilities.

We go from Accra to Glasgow, to Oxford to London and back again, examining how place, community and circumstance shape identity, drive and desire. The diasporic dance, choreographed to the key of confusion that comes from straddling cultures, is present but not overplayed. Ultimately the story calls us to question our definitions of home, how we can better feel at home in ourselves and why the most isolating spaces are often those shared with the people closest to us.

I asked Selali about the phenomenon of love becoming lazier and less perceptible with proximity. He said: “It’s easy to get complacent with people who are close to you and not do love as a verb. [You] think because you are in love, that’s enough…that’s why people often feel undervalued. With people who are closest to you, love gets harder to see through all the annoying stuff they do and all the many reasons why they irritate or deeply hurt you… Often it’s too late that we get reminded that the love is there.”

We also spoke about how love is sometimes overshadowed by expectation. In the novel, Abena and Kodzo work tirelessly to incubate their children (and to a certain extent, each other) from the pain and insecurity they experience in their own lives. Unspoken expectations bred by an instinct to protect, manifest as phantom pressure to which everyone responds differently. It causes rifts in the family and each character experiences resentment triggered by the failures or successes of another. It’s a feeling that Africans in all parts of the world know well and those of us brave enough to name it, may start to doubt the extent to which our ambitions are our own.

“All parents can use their children as clay pieces to mold into versions of themselves and that can obviously be harmful.” Selali said. “It happens a lot with diaspora parents because it often feels like there’s so much more at stake and so much they didn’t have the opportunity to do… But as well as parents projecting their dreams, I’m quite interested in parents projecting their fears. There are a lot of fears pushed onto children and that really forces them into boxes of what they can and can’t do. I think the fear of not being assimilated is one of the reasons why lots of African kids [in the diaspora] don’t learn their mother tongues. Conversely, [diaspora] kids don’t always take on those fears because they grew up in a different culture. That can be a source of tension too.”

Much of the tension in the novel is conveyed through dialogue, which Selali yields skillfully to present the conflicts that exist between characters. An exchange that’s echoed in my mind since reading the book is when, in the first chapter, Abena says to her husband “My children don’t need me here anymore. Neither of them. I didn’t come to this soil to set down my roots, I came here to plant seeds…” Kodzo responds “I walk to his grave every day. That’s ours. That coffin is our root in this soil. I can’t leave him.” A clear opposition is drawn, nobody backs down. With just a few lines of text we get so much insight into the marriage, bound by a shared willfulness and mutual devotion to their children, ruptured by rival expressions of nostalgia and regret.

Selali admitted it was a challenge to arrive at a place where each character has a distinct voice and each line of speech an express purpose. “A lot of thought went into the cadence of the speech, the fact there are lots of different accents and how I chose or didn’t choose to codify different languages.” He said, referring to the inclusion of Twi, Ewe and Scots in the writing. Regardless of your familiarity with these languages, the dialogue is digestible, dynamic and endlessly intriguing. It’s a testament to Selali’s belief that “dialogue is so much more fascinating when the words don’t directly reflect what the discussion is about.” As such, he serves his readers passages steeped in realism and dripping with dramatic irony.

Selali is a masterful storyteller, conjuring images so vivid they provoke physical reactions. As well as being an exceptionally talented writer, he is also a doctor and musician; the grace, precision and tenacity necessary for all his occupations most evident in the construction of Elom’s character. In his adolescence Elom is impressionable and overstrung, hiding his desperation for approval under a thin veneer of rebelliousness. He gets in over his head, playing at heterosexual teen lust to a backdrop of thumping bass, “velcro sucker kisses and the rustle of competing fabric.” As an adult, he is cautious and attentive, grasping for unbridled intimacy that always seems just out of reach.

Like all of us, Elom is the sum of many contradictions– messy, sometimes unlikable, often frustrating but fundamentally endearing. For Elom, the tension within his family is indivisible from his inner conflict, causing him to falter in other personal relationships. As he grapples with his sexuality and social standing, he is constantly seeking validation from family, in friendships, through sex, romance and his career, all the while feeling at the edge of things. He spends much of the story in search of belonging, yet resistant to share his full self with others.

In our conversation as in the novel, Selali provides no antidote to Elom’s existential sense of separation. “I want to say something trite about finding community or about being yourself,” he said “but those things are hard to do and I don’t really know if they answer the question, which is how do you not feel alienated in the world? Sometimes it comes from you and sometimes it comes from the world. Because the world is alienating… I think it would be dishonest of me to try and give advice about that.”

That being said, the story isn’t void of hope or levity. Be it through the soft grasping of hands on a compound in Accra, an orchestra of laughter in a kitchen in Glasgow or the electrifying embrace of the cold Atlantic on the Hebridean coast, we’re reminded frequently just how vibrant and enrapturing life can be. The characters connect with each other, themselves and the world around them by indulging in music, food, nature and play. Flavours, textures and melodies come alive on the page, drawing us further into the scene and providing reprieve from the heavier themes covered in the story. Stereotypes are subverted and despite the grief, there remains much to celebrate. Particularly in the case of Abena, arguably the character most at odds with her environment, who Selali confesses was his favourite.

“Abena’s my homegirl.” He said, “She’s a badman. She’s worked so hard for other people but she’s not a wall flower and she chose to do that. She chose to make the sacrifices that she did, she’s an active participant in her life and maybe she’s quite late to her final decision to choose herself but she does choose herself and she doesn’t regret the life she’s lived even though it’s a difficult life.” If love really is a tightrope between freedom and control, as the book’s tagline suggests, then Abena walks it with the poise and dexterity of a circus acrobat. To Selali she exemplifies “a noble kind of love.” in her ability to be selfless and nurturing without neglecting her inner fire. “I really enjoyed getting to know her.” He closed, “I think she’s really bold.”

The same can be said for the author himself, who drew on inspiration from across the African literary zeitgeist to create something entirely unique and compelling. The influence of Chinua Achebe and Mariama Bâ whom Selali respects for their “holding of the political in personal stories.” is palpable in Before We Hit the Ground, as is the “moral fortitude” of Ousmane Sembène’s writings. Buoyed by the works of his queer African contemporaries like Olumide Popoola, Chukwuebuka Ibeh and Musih Tedji Xaviere, Selali was able to take risks with his debut, writing with a clarity and confidence that leaves us at once satiated and curious about what’s to come.

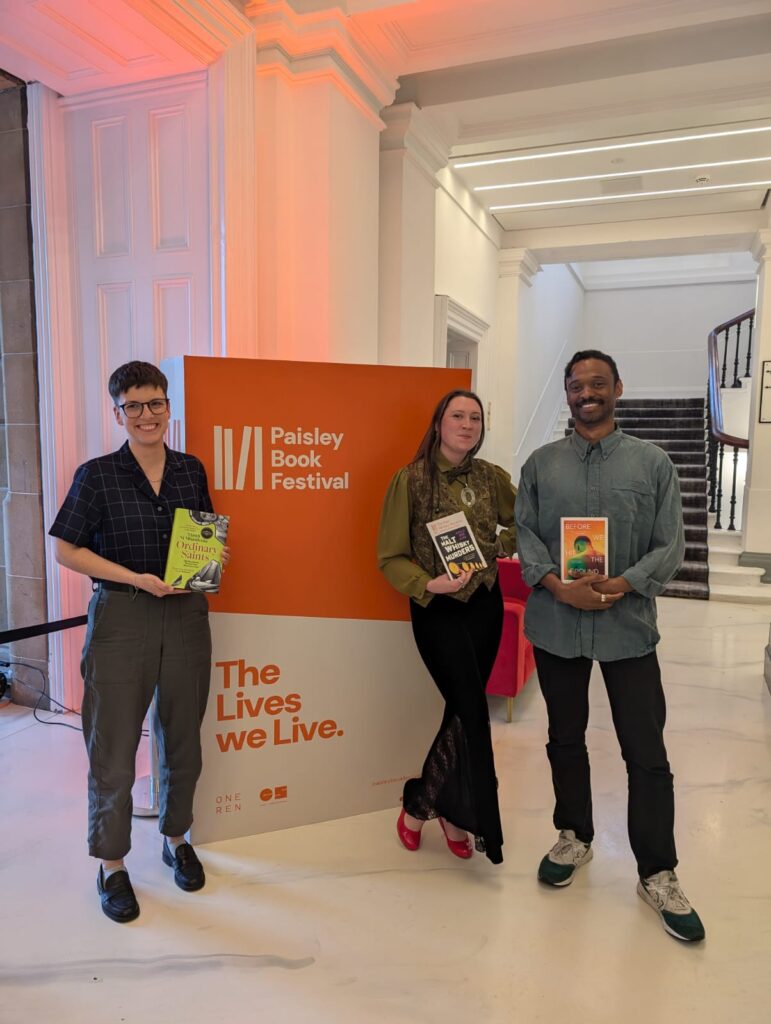

Born and raised in Glasgow, with a couple of years spent in Accra, Ghana. Selali Fiamanya has won a place on the inaugural Breakthrough Novel-Writing Course for Black Writers, run by Curtis Brown Creative and supported by Curtis Brown Literary Agency. He was named runner-up in the 2021 Pontas & JJ Bola Emerging Writers Prize, and won The Borough Press open submission competition with Before We Hit the Ground, his debut, which was published in February 2025, and was longlisted for Scotland’s Saltire Literary Awards 2025.

Memuna Konteh

Memuna Konteh is a multi-disciplinary writer who specialises in the

intersections of identity, culture and politics. Her work has appeared

in Thiird magazine, Reader's Digest, Glamour and elsewhere. In 2021 she

was runner-up in Hachette’s Mo Siewcharran Prize. She is currently

working on her debut novel.