Water No Get Enemy stands as one of Fela Kuti’s greatest artistic triumphs. Like much of his works, the song is a scorn at Nigeria’s oppressive military regimes in the 1980s and 90s, and their characteristic intolerance of dissents. Through its lyrics, Fela frames the song as a warning to the “enemy of water”—human greed. He sees dissenters who speak truth to power as essential to life as water itself.

Rooted in Yoruba spirituality and divination, the song stresses water’s invincibility and its inevitable, violent retaliation against those who attack it. The repeated line, “If you fight am, unless you wan die” serves as a stark reminder that opposing fundamental truths leads to self-destruction.

Alfonso Arteaga Rodriguez perfectly captures this fundamental truth about humans’ self-destructive relationship with water and nature in his short speculative fiction in the anthology, “Quizzani and The Eagle”, published bilingually in English and Spanish:

“I have heard of a human poet, the eagle answered, who wrote: ‘Man only wants his species to end, while we daily fight to perpetuate ours.’ The poet questioned which of the two species really was the animal. What is going on with you humans? Why this self-destruction? Why do you pollute the water? Don’t you see that water is life for you and for us? Without water, the trees that give us the oxygen we breathe would die. We would die too, of not having water to drink. Your people who depend on water to irrigate your crops will die and the entire planet will die. Help us please! Man in his desire for wealth is contaminating the waters; every day toxic substances and garbage are dumped into the rivers to pollute the fish and kill the reefs. When these substances reach the sea, whales, dolphins, sharks, among others, stray from their routes and end up stranded on the beach sands, where many of them lose their lives.” (109)

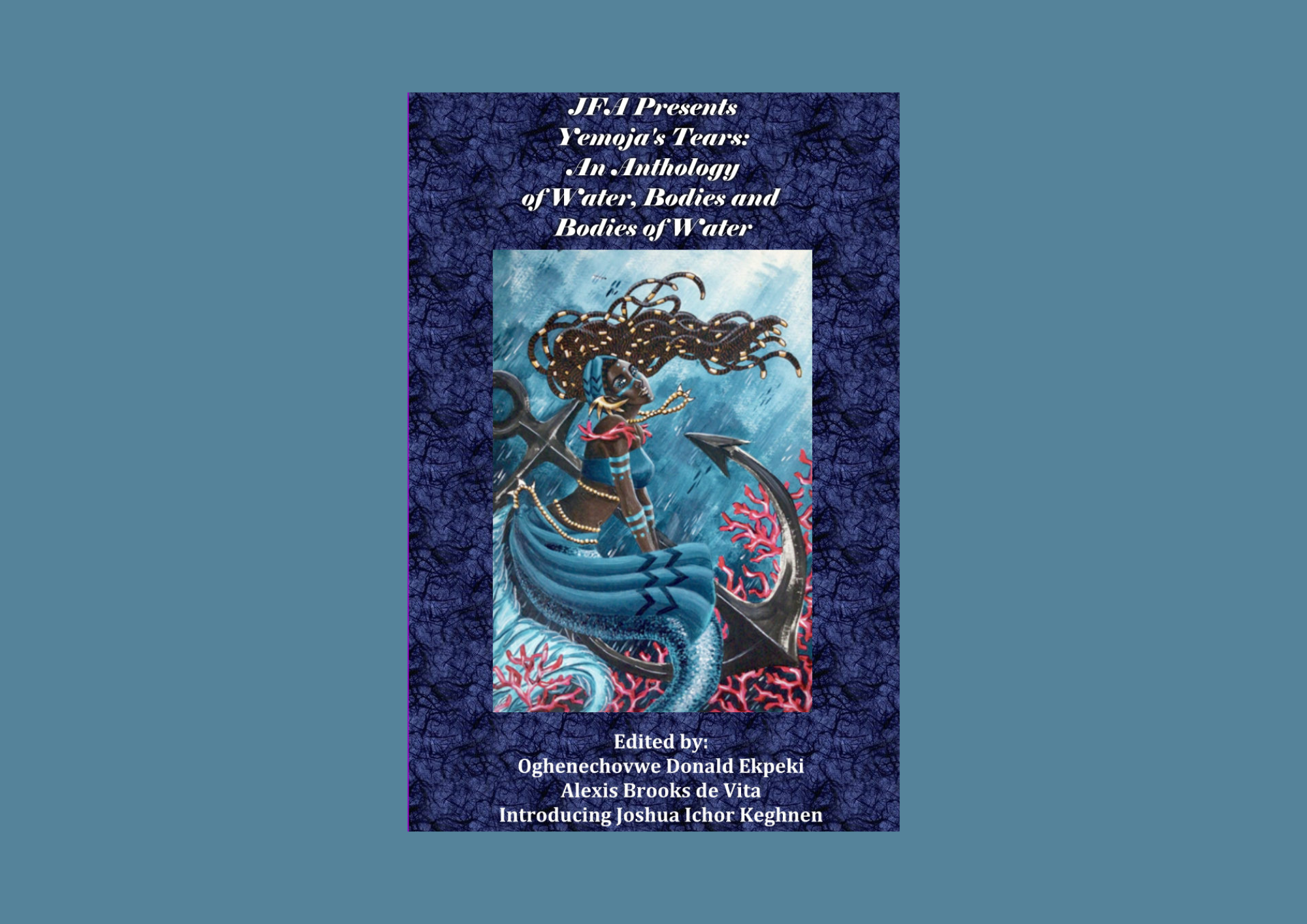

Yemoja’s Tears: An Anthology of Water, Bodies, and Bodies of Water, edited by the trio of Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, Alexis Brooks de Vita, and Joshua Keghnen Ichor, is a powerful collection of 26 works that highlight the perilous consequences of human recklessness on Earth’s ecosystems. Through fiction, poetry, and essays, the anthology underscores the urgent crisis of potable water scarcity while offering pathways toward solutions.

My own encounter with this crisis struck on the last Eid day. Traveling to my mother’s village, 12 miles from Kano, I forgot to bring water as I used to. A mistake made grievous under the unforgiving 41°C sun. After two hours, parched and desperate, I asked for water. They brought it chilled, something that made it alluring to my dry throat, but some particles in the water stared at me and I became frightened. Typhoid, a disease borne by contaminated water, had taken my high school girlfriend years before, and since then, I had a phobia for it. My trepidation for unclean water trumped. I spent 7 hours in the village with a dry throat. For me, it was safer to risk dehydration.

For this village of over a thousand people, clean water remains a pipe dream. Many don’t even realize the danger lurking in every sip. Yet, amid the despair, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s opening poem, “Source“, kindles hope. He reframes the global water crisis as a catalyst for collective action, writing:

“I feel strong when weak /Weakness lends me strength /For the desert /Is the source of the sea” (15).

The anthology, like these lines, does not just mourn what is lost. It calls us to fight for what remains.

I find Eileen Gunn’s “Whose Water Is It, Anyway?” to be thought-provoking and engrossing. The writer narrates, in what looks like a personal essay, the dilemma of conserving an expensively drilled well in an environment beleaguered by receding water table and sharing the scarce water with a neighbour in need but who uses the water extravagantly. The writer asks the neighbour to use the water for just cooking and drinking. “Water belongs to everyone,” is the response he gets. So, he cuts off the pipe connecting water to the neighbour’s house and asks him to be fetching in his house going forward. In the concluding paragraph, Gunn asserts:

“The seasonal water insecurity that I remember from my youth is trivial compared to what is happening in Africa and the Middle East.” (66)

Solomon Uhiara decries the exorbitant cost of water in the Nigerian state of Bayelsa despite its location around several water bodies and offers a realistic solution for policy makers to adopt. The rising cost of potable water in the state arises from hydrocarbon discharge and oil spillage that contaminate the water.

“It is ironical that several water bodies snake within and around the area, and some even channel into the great Atlantic, yet getting clean drinking water is like hitting a jackpot.” (67)

Wuraola Kayode’s “The Revenge of Yemoja” is a speculative tale about the supernatural consequences of environmental exploitation. One passage stands out for its sharp critique of climate injustice—how the wealthy, in their insatiable pursuit of profit, are often the ones who ravage the planet, while the poor suffer the repercussions. A chilling line captures this dynamic:

“She had once admired Mr. Akoko. Then she joined the police force and learned that human beings were terrible and could be even more terrible when they had a lot of money.” (92)

Inspired by his visit to Lake George, Gillian Pollock’s “Water Guzzlers and Time Wasters” bemoans the water crisis in Austral and only finds solution to the problem in migration.

“I’m writing this angry note at this angry moment because water cost me ten percent of my salary this month. I don’t know how the less-well-paid manage. Me, I manage by leaving.” (105)

I find Mary A. Turzillo’s “Water Is Life, Water Is Death, There Is No Truth or Joy Without Water” to be the most evocative piece of the anthology—a raw, impassioned cry for universal water justice and an end to inexcusable scarcity.

This anthology reminds me of Nana Sule’s “Water”, a short fiction about two women divided by wealth. The second woman, a thirty-year-old mother of nine and grandmother of two, resorts to using rags during her period. Sanitary pads and tampons are beyond her reach. When lockdown halts her and her husband’s income, she abandons contraceptives; another pregnancy becomes the only “affordable” choice, sparing the precious water needed for far pressing needs than washing her sanitary rags.

An anthology of awareness, in my view, should prioritize simplicity and accessibility over artistic elitism. Unsophisticated readers may find some of the pieces here to be intractably difficult, but Yemoja’s Tears triumphs in its diversity—voices from across the globe uniting against water injustice and ecological abuse. Every poem, story, and essay resonate with undeniable urgency.

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu

Ahmad Mubarak Tanimu is a freelance book reviewer and fiction writer based in Kano. In June 2024 he was selected for the Flame Tree Project that aimed at bringing new voices in Northern Nigerian literature, facilitated by two past winners of the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim and Chika Unigwe. He was a finalist in the book review contest of the festival books of the 26th edition of Lagos Books and Arts Festival (LABAF)