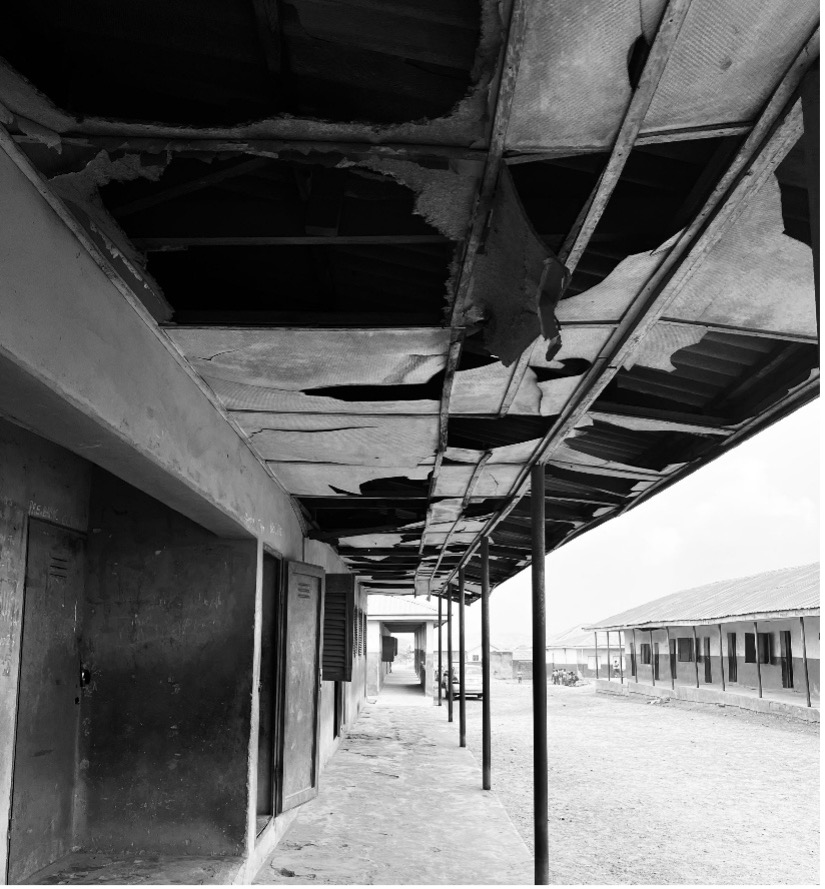

I found myself walking through empty school corridors in Ibadan, drawn to buildings that once buzzed with the voices of school children but now echo only with my footsteps. The covered walkway stretches ahead of me, its damaged ceiling creating patterns of light and shadow on concrete that shows its age in stains and cracks. The repetitive columns create a rhythm that feels both institutional and intimate, and through the gaps, I glimpse other buildings continuing the same architectural conversation.

These structures tell a story I’ve been wrestling with – how spaces built for learning become monuments to broken promises. Moving beyond the corridor, I encounter two parallel building blocks facing each other across empty ground, their windows march in perfect formation – small, identical, efficient. The space between them feels too wide and too quiet. This is architecture designed for crowds, now hosting only wind. The modernist lines are still there, clean and purposeful. The optimism that went into these designs is still obvious, the belief that good architecture could help build a better Nigeria.

A dirt track runs between other symmetrical buildings like railway lines heading toward an uncertain destination. The perspective pulls you forward, and the buildings on either side stand as witnesses to whoever might still pass between them. Walking this path, I’m struck by how these spaces have aged; some with dignity, others less gracefully, but all bearing witness to what happens when maintenance becomes memory.

Nature, it seems, has its own relationship with these abandoned spaces. Grass has claimed the courtyard in front of one low building, growing almost to the roofline. It’s a beautiful confrontation, nature’s persistence against human planning. The building waits behind the grass like something half-remembered, part of a landscape where infrastructure and environment negotiate their own terms.

In this same landscape, a cylindrical water tank presides over a long, functional building, infrastructure in its purest form. Here, in the background, I caught a glimpse of school children walking by. Some of these spaces still pulse with life, even as others fade. The contrast is striking: utilitarian structures built to serve communities, some still fulfilling their purpose, others standing as monuments to absent inhabitants.

The weather has written its own story on concrete walls throughout this architectural journey. The stains and discolouration create unintended patina, recording seasons without care. The building’s bones remain strong, but their skin tells a different story, one of time passing, resources redirected, priorities shifted.

This isn’t about pointing fingers. It’s about understanding how buildings live and die, how they serve communities, and how they’re abandoned by them. Each frame captures a moment in this lifecycle: concrete meeting weather, nature reclaiming space, infrastructure outlasting its support systems.

~

These photographs emerged from my ongoing interest in how buildings age and how communities relate to their built environment. As someone trained in architecture, I’m fascinated by the gap between design intention and lived reality. The schools I documented represent a particular moment in Nigerian history, post-independence optimism translated into concrete and steel. The modernist aesthetic spoke of progress, efficiency, and faith in institutional solutions.

Many years later, these buildings exist in various states of use and abandonment, each telling its own story about resource allocation, changing priorities, and the challenge of maintaining public infrastructure. I’m not interested in easy answers or simple blame. These images ask questions: What do we owe our educational infrastructure? How do buildings shape the communities that use them? What happens when the support systems that sustain institutions fail?

This work sits within broader conversations about educational equity and infrastructure in Nigeria, but it approaches these topics through the specific language of space and form. Buildings, after all, are not neutral. They embody the values and priorities of those who create and maintain them.

All photographs captured in Ibadan, Nigeria, 2025.

Taslimah Woli

Taslimah Woli is a Nigerian architectural designer and visual storyteller whose work explores the intersections of space, memory, and human experience. She is deeply interested in how design reflects the quiet negotiations of everyday life. Through her lens, Taslimah captures overlooked buildings on the verge of erasure, textures that tell stories, and corners where light reveals hidden narratives. Her work has been published on Lolwe and Isele. She is less interested in spectacle and more in the kind of beauty that invites contemplation. Rooted in empathy and reflection, her work is shaped by her architectural training, her love for cities, and her belief that design and photography can serve as both mirror and memory.