I remember the first day I saw my period. Ha! That day. I had never felt more ashamed of being female. A milestone tainted with shame. Mother congratulated me on womanhood, but it felt more like an induction into a world of shame, stigma, and silence. She lectured me on the “thou shalt” and the “thou shalt not”, the prescriptions and proscriptions like the Latin grammarians. “Now that you’re a woman,” she said, “keep your legs closed, be mindful of your company, avoid male friends, and beware: Sharing a bed with a man will lead to pregnancy.” By the time Mother was done with me, I went to the backyard of our apartment and bawled out my eyes. I cried because I was scared; scared of this womanhood I was stepping into.

I am hesitant to state that my fondest memories of my parents are tinged with bitterness. To do so would overlook the times when our house truly felt like a home. Ah! I remember those moments. The excitement when they surprised me with a toy aeroplane, and my sister with a toy helicopter. Our ecstatic shouts filled the air as we expressed our gratitude, jumping onto my father’s lap and exclaiming, “God bless you, sir,” with unbridled joy.

There were also occasions when Mother prepared mouth-watering dishes or brought home fruits. She sold fruits somewhere in Ketu and returned with leftovers on some days. I remember my siblings and I secretly praying for fewer customers so that she would bring her surplus ware home for us to enjoy. Meanwhile, my father, even though he was partly unemployed when we were young, would purchase foodstuffs from the market and take on kitchen duties. The Oha soup with so many leaves and chunks of meat was a particular favourite. I didn’t like it at first because it was like eating porridge—without yams—and swallow. But when I realised that our parents were not like the Olus whose children could pick whatever they wanted to eat, I adapted.

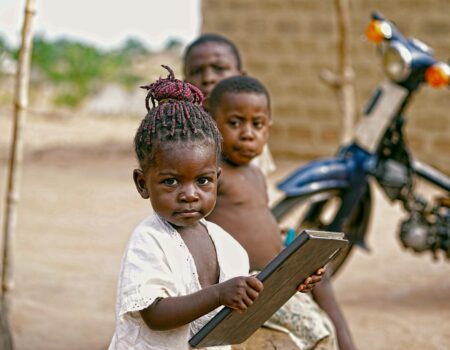

Father and Mother seemed to us like a duo made from heaven. They would sit in the room and share memories from their childhood. Mommy said she used to aspire to become a teacher in her time. Her dad was a hunter who brought home different kinds of bush meat. I didn’t like the idea of bush meat because I believed it unjustly to kill wild animals. I never told her this though, because she would say “too much book” was my problem. Mother told us that she managed to finish her primary education but had to drop out when her father could no longer afford to send she and her siblings to school.

It was also fun to witness the playful banter and good-natured arguments between my parents. Father schooled up to secondary school level and could speak English better than Mother. During their arguments, he would switch from Wafi—Warri-accented Pidgin English—to proper English, and Mother, trying not to be the odd one out, would switch to her variant of the English Language. “I were no there o…” We would all burst out laughing at her attempt to speak English.

As we grew older, all four of us began to notice cracks. Maybe they were always there, and we were just too young to notice. The earliest memory was noticing that Mother and Father didn’t exchange words other than a grumpy “good morning”. Then, it graduated to having discussions all through the night. There was no difficulty hearing them because the parlour was too small to accommodate us so we had to share a part of the room with them—the floor. I didn’t exactly pick out the topics, but I knew that they were arguing. After that, we would hear the bed creak. Creak. Creak. Then silence.

I became exposed to problems too early in my life. Whenever Mother and Father were fighting, the latter would call us aside when Mother had gone to the shop. He would tell us things that were not right for kids who were not even ten. Consequently, we believed one side of the story without hearing from the other party. We ended up despising Mother heavily for always causing problems in the house. So, whenever they fought, we mumbled under our breaths, calling her a troublemaker. When Mother noticed that no one supported her, she would sit on the floor and weep. Then, she would call Father by his name and cuss him for darkening our minds against her.

What my parents didn’t teach me while they were busy fighting, I learned outside. I was fresh out of secondary school and the fight had not stopped. I was tired and bored. Arguments always ensued as to whose turn it was to cater for us. In the end, neither one did. With no food at home, I had to start looking elsewhere.

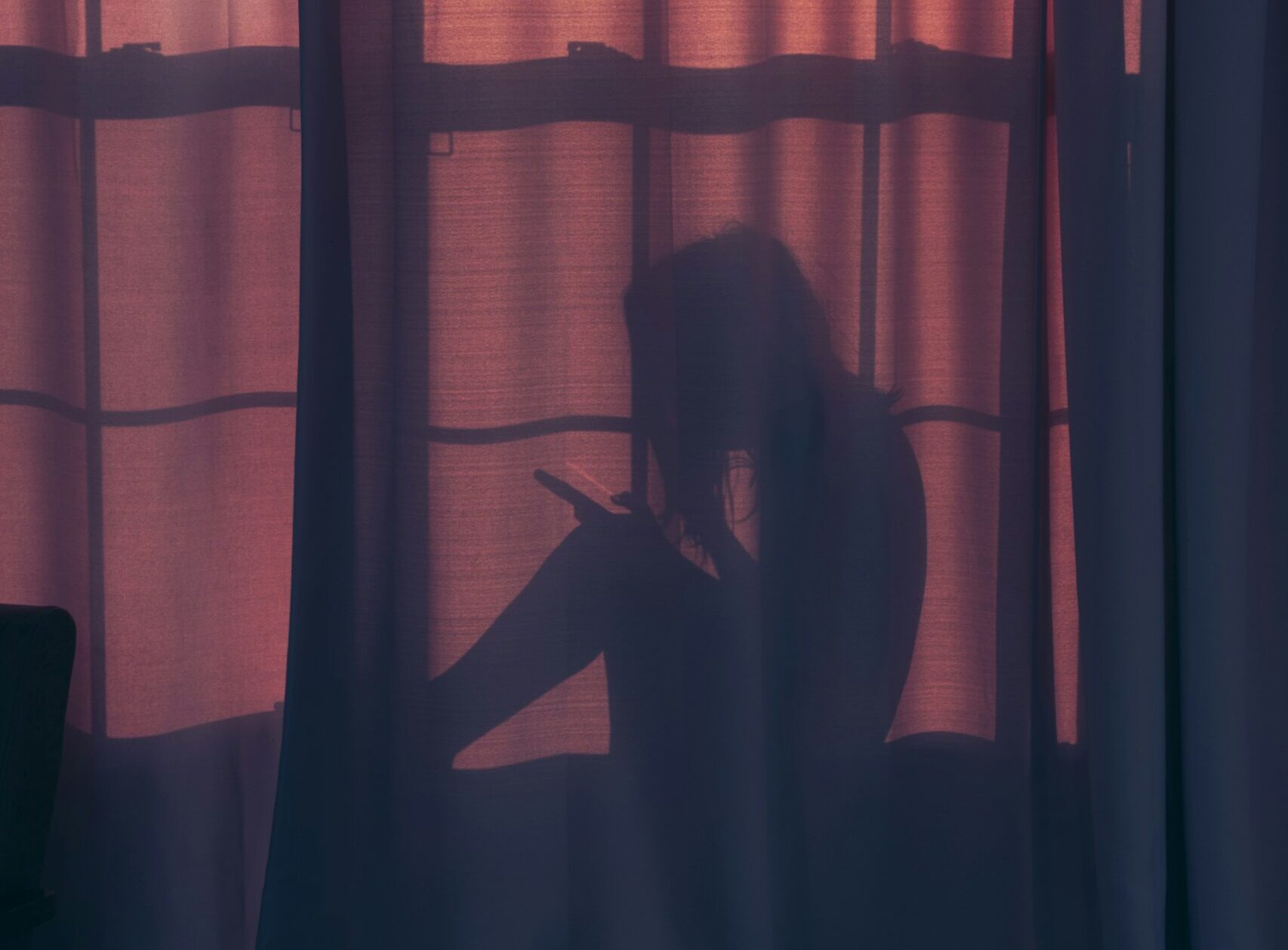

A male neighbour had his eyes on me. He invited me over for “a talk”. It was two days before my sixteenth birthday. I was bored and naïve. What was there to lose? So I went for this “talk” and came back with my panties soaked. I don’t like to call it rape but he never told me it would be a bloody talk. I lived the rest of the following week in fear of being pregnant. Fear and shame swallowed me up, making sure that year’s birthday was the absolute worst. I couldn’t look this neighbour in the eyes. In fact, I avoided him until his family relocated abroad one month later. Even after he left, I could not tell anyone what had happened.

Father had a job now, and he was always busy at it. He only came home three times in a week. I didn’t have to worry about him discovering. But Mother suspected something, the way mothers did when their daughters were pregnant. Whenever she came back from work, she would pull her ears—if calm—or hit her knuckles on the table—when angered by father—and say again and again that anyone who came home with pregnancy would be on her own. Sometimes, I feared she had been told something and would finally come to me, throwing the truth in my face. But that never happened. Telling my mother—who had earned the name “tigress” from my brother’s friends—about my experience wasn’t an option. I knew she would have called me ashawo—prostitute —and other derogatory synonyms she could think of in her native tongue.

I learned to wear my shame with pride; shame that made me mute when my friends spoke about their virginity; shame that convinced me that I was filthy because I had allowed the devil to desecrate me—God’s holy temple. But there was something unique about this shame…a je ne sais quoi. I was no longer haunted by Mother’s words about getting pregnant; I knew better. I no longer bothered to challenge Pastor Mrs., Mummy Pastor, or Momo, when during the meeting for young girls, she would tell us not to give in to the flesh. Sometimes, I wanted to ask whether boys were the flesh as they were the ones who requested sex from me, including her son. I wanted to ask why there was never a meeting for boys, other than ones teaching them to provide for families they didn’t have. Once, I asked whether the devil couldn’t use males too. She laughed and said the devil used Eve, not Adam. I simply stopped listening to her.

“So, why do you always antagonize love?” I hear someone say. I open my eyes and seven years have passed. Now, I am a penultimate student at the university. My roommate’s question pierced the air, pulling me from the depths of thoughts I didn’t know I was subsumed in. My mind wanders like an evil spirit. It has been a long journey since the days when I carried the burden of shame from being sexually assaulted. Meeting others who shared similar experiences at the university had gradually worn off that shame. I had begun to regain control over my life. I became a born-again Christian and rediscovered my passion for writing and literature, things that had faded into obscurity after the incident at 16.

Before responding, I allow a small smile to grace my lips. I reflect on the notion of love, as my roommate saw it. My parents, who she says are supposed to embody my first experience of love, remain a puzzle I will never piece together. While they care for me in their own ways, it feels more like duty than love. My relationship with them is fraught with unspoken emotions and unknotted connections. I don’t understand them. They don’t understand me. It’s just the way things are.

Silently, I contemplate my roommate’s question for the umpteenth time, but words elude me. Instead, I give her another smile that does not reach the sadness in my eyes. As she shifts the conversation, thankfully not noticing my discomfort, my mind wanders to the turmoil within my family. Mother, consumed by jealousy and suspicion, will be somewhere tracking Father. She will be checking his wardrobe to find evidence that he is cheating on her. She will be going to his shop to hopefully catch him in the act. Father will be at his ironing table, pressing clothes, sighing and sighing, burdened by the due bills he has to pay—shop rent, house rent, NEPA bills, etc., etc. Gradually, he will be fading away like some clothes overworn, perhaps at the realization that nothing he does will make him richer.

I sigh again, conceding to the reality that not all families are destined for happiness, and mine is “not all families”.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is passionate about African literature and dedicates her time to amplifying it through book reviews and video content. She won the Atipo Prize for Book Review 2023 and the Afrocritik Inaugural Prize for Literary Criticism 2024. She was the second runner-up in the After The End Book Review Competition 2024. Her work has appeared in Afrocritik, JAY Lit, Afapinen, Kalahari Review, Bella Naija and elsewhere. Connect with her on Instagram, X, Facebook, and LinkedIn: @evidence_egwuono.