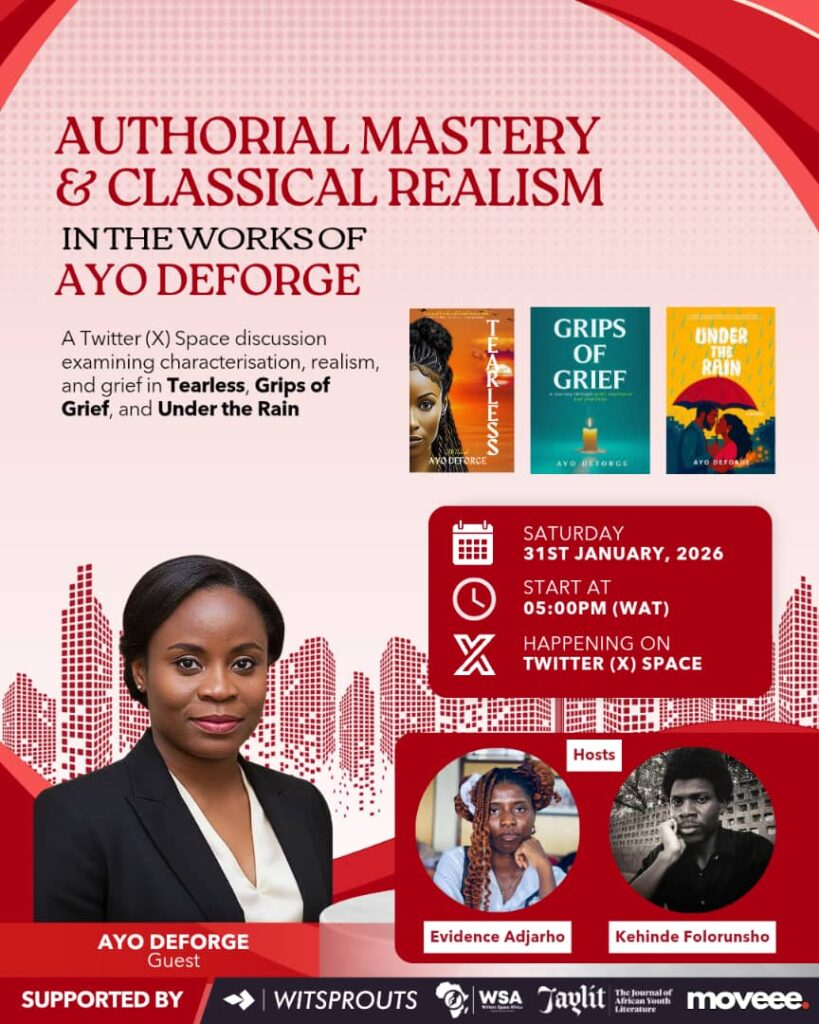

From the inception of the novel as a literature genre throughout the centuries of its engagement and to date, critics have always found the representation of society in certain intrinsic elements deployed by the writer. The elements of the story serve as rigid indexes to the themes of the age. For example, a typical 20th Century narrative professes the concerns of the period by its plot. The preoccupation of Black American protest is found in the roguish protagonist. Even so is setting a critical constituent of the urban fiction which lays bare the anomaly of city dwelling. Based on this proviso, there is a talking point about the evolution of female representation in the works of Ayo Deforge. For the purpose of this discussion, Tearless (novel) (2023), Grips of Grief (memoir) (2025), and Under the Rain (novel) (2025) are selected for evaluation.

A keynote point of interest in these three texts, to begin with, is their classical realism. Let us say that realism is generally what the authentic text so conceives that it dissects the position of social standards on matters which affect our very humanity. Of course, we know the outcome of such undertakings. It has always been an unorthodox view of the specifics at stake; the very problems we have only adapted to, not because they are all palatable but because they feel too existential to denounce. Conversely, reality would be the sum total of biases, sentiments, and allied forms of fallacies we are conditioned to exist by. What art (literary texts, precisely) does therefore is to sample these two and leave the reader to judge their own disposition to facts. I say “facts” because the immediate purpose of art is not truth but pleasure (courtesy of S.T. Coleridge).

On this note, the classism about Deforge’s realism is in her characterisation. The veritability of a literary text, no doubt, finds footing in its universality and permanence. I aim to highlight the similarities between Ayo Deforge’s go-getter Lami in Tearless and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). In the latter, the female protagonist voids social constructs in the emerging society that relegates women to housewives. She leaves the Reed household where emotional abuse and neglect militate against her dignity and ventures into the world, independent. Her remarkable success in the end and her choice of marriage, which negates the expectation about, points the reader to the immeasurable soundness of women’s sense of ambition, essence, and purpose outside of economic dependence of marital obligation. Similarly, Lami’s immediate push, after suffering emotional and physical abuse from her father, is economic dependence. She worked in a school and took private tutoring jobs on the side to earn extra income, projecting herself as an ambitious, young lady whose survival instinct outweighs the sting of family neglect.

Another is the sacrificial affection of Bolaji in Deforge’s Under the Rain and Thomas Hardy’s Jude in Jude the Obscure(1895). Both characters depict the realism of masculine subservience. In essence, both characters show that outside the privileges of making a pick, the bearings of emotional soundness rests with women. Whoever reads the dummy portrait of Jude under the mores of his Victorian world will understand that Susan (or Sue) Bridehead sees beyond that standard and uses Jude’s emotional security to lay bare the self-contempt of repression associated with the ‘understanding’ male. Leaving Jude between friendship and love, Sue dispels the superstition about compulsive romance. But even within that amnesty, both parties lose their joie de vivre to experimenting with that possibility. The last sentence of those novel hints at a lifetime cessation of happiness for Sue upon Jude’s passing. All that I have pointed out here is similar to the fate of Bolaji in Deforge’s Under the Rain. Although this is no Victorian age, the realism of both texts makes them look contemporaneous so that the contemporariness of Deforge’s story projects a palpable character emerging in the host of thematic preoccupations of the post-modernist lived experiences. Bolaji and Jude point to the unconscionable self-sabotage of the dummy male in a bid to triumph against the backdrop of compulsive romance.

I come to Grips of Grief. It takes its own momentum from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). Offered’s experience and the agony of her childlessness is another existential crisis women suffer. Similarly, Flora Napa’s Efuru(1966) details the angst of Efuru, the protagonist, who, despite her economic prosperity, is not accorded the full regard of her womanhood. Although Deforge’s narrator in Grips of Grief eventually births a child, the inner conflict experienced is no different from how Efuru braves her inability to have a child again. A common element of their experiences is the theistic values deployed by both writers (Nwapa and Deforge). Efuru is routinely religious as she sacrifices to the god of fertility while Deforge’s narrator has an intermittent reverence for God’s supremacy. Until the climax stage of the plot where she gets tenacious, the narrator still places a premium on her sense of complementarity in marriage and her ambitious-driven living.

The writer and the imagination of society is a framework of ideological understudy in our emerging narratives. It is incontrovertible that society exists as a microcosm in the mind of the writer; therefore, it is anomalous to impose verisimilitude on a parochial conception of the conflict. The writer is obligated to preserve the sanity of tradition right in the scheming that produces the active reader’s ultimate response. Point? We cannot dispute our world with its erstwhile narrative of socio-cultural gratification: there are ‘sins’ that inspire an honest exploration of man. And this is what Deforge achieves. It is a balance between women and men; economics of love and the politics of choice.

It is this contiguity of classical portraits that earns Deforge her authorial mastery. Join us for a powerful and illuminating conversation as we explore how her deeply personal reflections have produced mordant expressions that have cut across generations of literary expositions. Ayo Deforge has inadvertently yet ingeniously woven her narratives into the relevant antiquity of women as predominant forces even in the face of social stratification, the dummy male, the trailblazer woman, and the universality of women’s experiences. The talk session will therefore examine these subtle areas of authenticity where the interest of an average reader may have been limited to the immediate aesthetics of their expected storyline, outcomes and responses. If you have ever wondered how personal history becomes literature, how a writer shapes a world readers never want to leave, this is a conversation you do not want to miss.

Come 31st January, 2026, the conversation will be hosted on X (fka Twitter) by Evidence Adjarho and I. The space would be live via Writer Space Africa’s handle.

Kehinde Folorunsho

Kehinde Folorunsho is a literary critic and a scholar of literature. His interest in literature spans poetry, visual arts and translation studies. He made it to the shortlist of the Atẹlẹwọ Prize for his Yoruba translation of Chimamanda's Ngozi Adichie's "We Should All Be Feminists"; shortlisted for the Gbemisola Adeoti Poetry Prize, 2025. As a book reviewer, he has been published in local newspapers. He is the recipient of the 2025 Ken Saro-Wiwa Prize for Book Review.

![You are currently viewing [Featured Post] Authorial Mastery, Characterisation, and Contemporary Realism in Selected Works of Ayo Deforge](https://jaylit.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Ayo-Deforge.png)