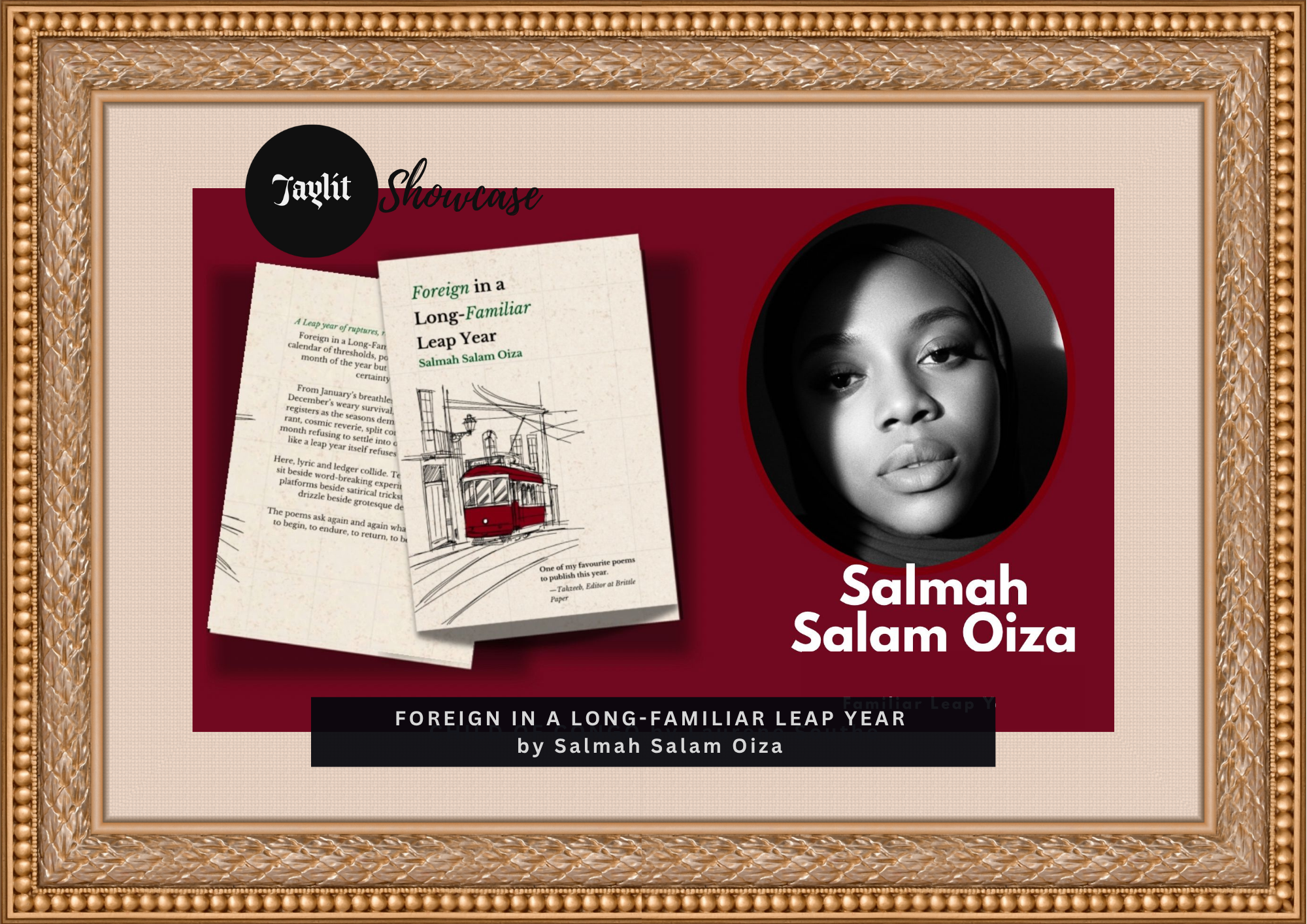

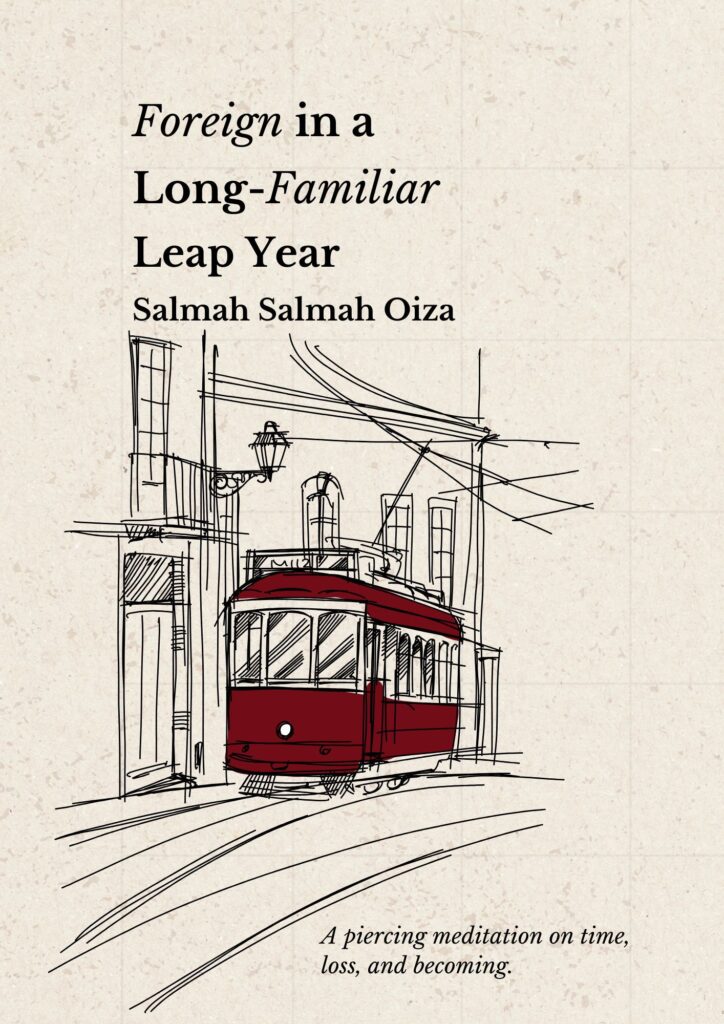

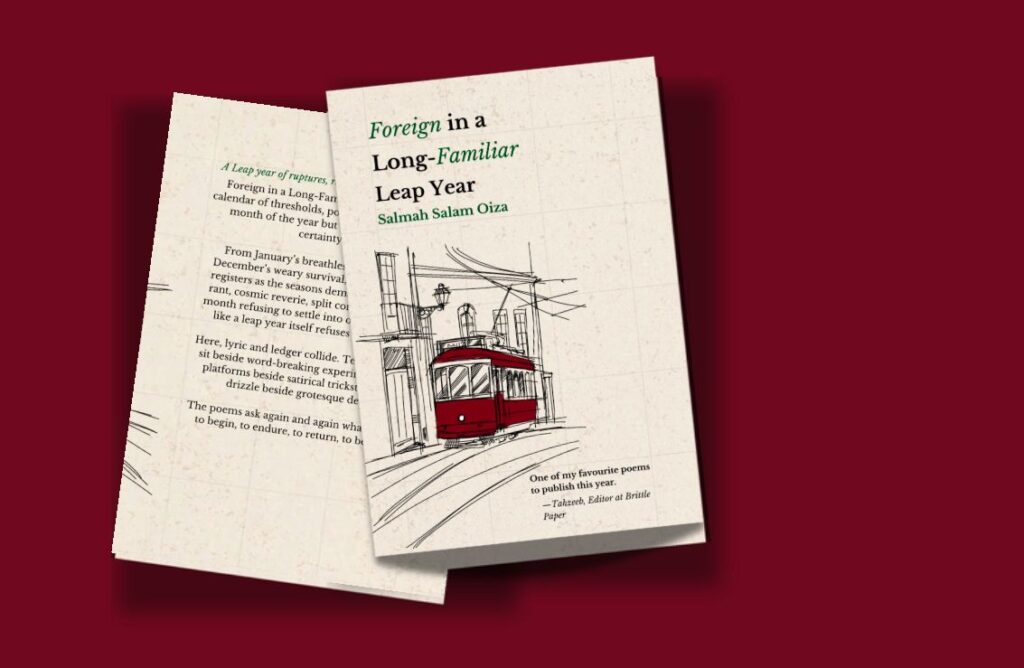

Somewhere between departure, return, and survival, Salmah Salam Oiza’s debut poetry collection Foreign in a Long-Familiar Leap Year was born. Written during her first year in the UK, the collection maps grief, migration, and memory across the passing months of a year. Bus rides, grocery trips, and shifting skies become charged with the strangeness of dislocation. From fragments on her phone, the work slowly unfolded into a body of poems that speak to one another—a lyrical diary of migration.

A Year in Poems

The book takes the calendar year as its frame—a way of holding otherwise unstable time. Each month becomes its own vessel: January for departure, March for longing, July for survival, December for quiet. Through this sequence, Salmah shows that grief, joy, and belonging rarely arrive together but instead unfold unevenly, like seasons. Time itself becomes another character in the work: there are days that feel endless, and years that vanish overnight.

For Salmah, this warping of time is inseparable from migration. Living between two places distorts rhythm—the pull of family back home, the strangeness of a new country, the echo of what’s been left behind. The poems attend to that distortion, to the ache of living across multiple timelines. And because each poem begins with feeling, form follows suit. When pain is sharp, the language turns clipped and spare; when the emotion needs air, the lines loosen and spill across the page. “I think of it as music,” she says. “Some poems are percussive, some more orchestral.”

Stretching Across Borders

One of the collection’s most striking pieces, “Spaghettification,” emerges from both personal intimacy and scientific metaphor. Salmah describes it as a love poem—one born in the quiet steadiness of someone who held her together during a time of profound unraveling. The term itself, drawn from physics, describes what happens to a body as it nears a black hole: stretched impossibly long, pulled apart yet continuous.

She says the word captured not only the science but the feeling—the tenderness and terror of being remade by both love and migration. To love, in that moment, felt like surrendering to gravity: to be drawn toward another even as the self-elongates under the pull of distance, dislocation, and desire. It became the perfect image for identity in flux—the sensation of being pulled between countries, cultures, and selves. “You become thinner in some ways,” she notes, “but also stranger, longer, unrecognisable.”

What begins as a love poem expands into an anatomy of displacement—the body stretched to contain all its histories, its intimacies, and its departures.

The Language of Contradiction

Poetry, for Salmah, is the most generous form for holding contradiction. Where prose often insists on resolution, poetry allows her to linger in uncertainty—to say and unsay, to hold truth and deception in the same breath. Migration itself is fragmented, and her poems mirror that fracture, refusing neat conclusions. “Sometimes,” she reflects, “the mind catches up only after the body has already spoken.” That urgency—the way language seems to surface from somewhere older and deeper than thought—is, for her, the heart of poetry.

Faith and Inheritance

Faith shapes not only the lens through which Salmah writes but also the cadence of her lines. Prayer taught her rhythm—the repetition, return, and restraint that give her poems their pulse. And alongside that faith runs the texture of her Nigerian upbringing: the folktales that moved like songs, the theatricality of Nollywood dialogue, the lyric excess of everyday speech. Together, they taught her how language can hold music, exaggeration, and truth at once; how a single phrase can carry both ache and laughter.

These influences are not opposites but inheritances, layered into the grain of her voice. They give her permission to write in abundance—to place grief beside joy, sensuality beside devotion, contradiction beside contradiction. Writing, for Salmah, becomes an act of reclamation: a way to bring colour back after silence, to name what prayer alone could not hold.

Community and Continuity

Salmah insists that writing thrives in community. “Go to open mics, join writing groups, share drafts with friends, swap rejections, celebrate each other’s wins,” she urges. For years, she hesitated to share her work, afraid it might feel cringe. “It felt like shouting into the wrong room,” she says. Finding her people—writers and readers who understood her sensibility—changed everything. What once felt like performance became conversation.

She also grounds her practice in pragmatism: submissions, timelines, rejections are part of the rhythm. “A rejection doesn’t mean the work has failed,” she says. “It just hasn’t found its home yet.” Whether self-publishing or building slowly toward larger projects, she values patience, craft, and above all, joy. “Because if the joy goes,” she reminds herself, “the work loses its pulse.”

A Companion for the In-Between

Salmah hopes Foreign in a Long-Familiar Leap Year finds readers in their own quiet, in-between spaces. It isn’t a book of grand declarations or conclusions, but a gentle companion—something to underline on the bus, to gift to a friend moving abroad or returning, to hold during those small, suspended hours of loneliness. If her poems can sit beside readers in those moments of pause and passage, she considers the work fulfilled.

Looking Ahead

The preoccupations that run through the collection—identity, intimacy, and faith—continue to guide her, even as she turns toward longer forms. “I’m curious about joy, sensuality, even humour,” she says. “Poetry will always be my anchor, but I want to stretch into narrative, into play, I want my work to keep resisting boxes.”

Her next major project is the novel Love Insha’Allah, set in northern Nigeria. It follows a young woman negotiating duty, desire, and faith within an arranged marriage—a story that extends Salmah’s long conversation with belonging and belief.

Between poetry and prose, devotion and defiance, her work keeps returning to one question: how do we hold contradictions without breaking? In that tension—held, sung, and stretched across pages—Salmah Salam Oiza has found her truest form.

Aishat Adesanya

Aishat Adesanya is the author of Funerals and Firecrackers (March 2025), her debut short story collection. She is a Yoruba hijabi who started drawing aged 9, before discovering her love for writing and publishing her first story aged 17.

Her writing has been featured in Witsprouts’ Love Grows Stronger in Death Anthology, Lion and Lilac Arts, The Journal of African Youth Literature, Hearth Magazine, Schuylkill Valley Journal, and elsewhere.

Aishat has been nominated for the Best of the Net and was a judge for the 2024 JAY Lit Awards. She writes from the West Midlands in the United Kingdom, as she continues to explore stories rooted in identity, resilience, and memory.