“Your feet are soft. From the moment we met, I knew.” Njavwa said out of the blue.

“How?” Sara asked. His observations were dangerous.

“It’s in the way you move.” He ran the nail of his little finger along her outer arm, and goosebumps formed.

“Sounds like one of the things you say that are only true in the moment.” There was some usefulness to resisting his theories and not falling too quickly into his ideas.

“Maybe. But this is an objective truth. Your feet are soft–all of you is soft.” He moved up to her face. He cupped her cheek, stroked the three beauty spots that marked the corner of her eye like Orion’s Belt marked the sky.

“Well, so are you.” She deflected.

“No. I am only soft to you.” He separated his body from hers and moved to her feet in one movement. Sara watched his muscles flex and relax as he held her favourite foot in his hands. He was right–he was hard but only soft to her.

He took each toe in his hands, kneading with practised, familiar pressure and releasing to mould the arch.

“I like this nail polish on you.” He said, sucking on her big toe. Seeing his full, dark lips against the emerald-green polish made her blush.

She summoned a diversion. “Did you do what they said you did?” She blurted.

“You mean did I rob the spa?” He stopped, and he held her gaze.

“Well, did you?” She sighed.

“I wasn’t there. But I knew the alarm code, and I shared in the profits.” He kissed her ankle, “Does that answer your question?”

Sara shrugged and offered her calf. He took the unspoken cue and cured her of the knots and tension she earned from wearing heels all day, every day.

“What else do you know about me?” She asked.

Nothing stood out to her about the day they met; nothing but him. Many other men worked at the spa, but she noticed his height, his depth and focused awareness of her.

“I know your mother is exhausted and your husband is a loser.” He said in a steady breath.

“That is obvious–he is a retiree, and he never worked.”

“I think society prefers the words pensioner and self-employed.”

“I think society is full of idiots. We are not here to pretend.” Sara snapped. Around him, she was able to grasp the truth by its sharp edges.

“How come your name is not spelled traditionally with the H?” He deviated.

“You’re going to call my husband a loser and then move on to nomenclature?”

“I don’t think you like talking about him.”

“I don’t. But Albert is part of my truth.” She sighed.

“Do you think they will ever find him?”

Everything about Albert was medium: medium brown skin, medium height, medium weight, medium penis. She remembered his boring naked body with no identifying marks tumbling down the crack in the ground and the concrete machine quickly covering him up like he was never there. He was as insignificant in death as he was in life.

“No. They never will. Unless they try to expand the roads again at election time and by then, who will care?” Sara said.

“The politicians, the journalists, the people, Mwebantu?” Njavwa pitched.

“Perhaps. But who will you be then? Whom will I be? In fifty years, every witness to Albert’s existence will be long gone.” Remorse stung Sara more for whom she had become than for what she had done.

“You’re right.” Njavwa sighed. “I shouldn’t think about it.”

“It was a good plan,” Sara said.

Homeless men of all ages turned the streets of Lusaka to their homes after dark. If they ever found Albert, he could easily be another one of the faceless, nameless beggars who died in the cold and were left there to rot.

On the record, Albert left a note saying he was leaving her to start afresh. The note was presented by his lawyer, who asserted that there was no property left behind. His family barely flinched. Men left women for younger, greener pastures all the time–especially men like Albert.

“I may have stopped school in Grade 12, but I am smart.” Njavwa beamed.

“I know that.”

“How do you know?”

“You didn’t drop out of school because you failed, you dropped out because you wanted more. The rest of us were not as courageous.” Sara’s eyes misted.

Njavwa took her hands in his, holding the silence until their palms sweated. He never said a word, but she could hear it all: his undying devotion, ragged adoration. He would do anything for her, and he had.

“I think you’ll be alive in fifty years,” Njavwa said.

“Why?”

“It makes sense. You’re an old soul. Look at your pillows, your handbag, and how you drape a coat over your chair even at the club.” He laughed.

The vintage French pillowcases matched the quilt at the foot of the bed, with their naked bodies splayed over them, she didn’t think he noticed.

“My bag was a gift from my mother, and I wear expensive coats, so I drape them to protect them.” She defended.

“Baby-Doll, many girls wear expensive coats, but very few know how to treat them.” He smiled.

Baby-Doll. Where did he learn to use words that rolled off his tongue and melted her?

“That’s girls from Kabwata, Bauleni, and whatever other compound of yours. Not here in Sunningdale.”

“Is that what you really think?”

“I didn’t mean that.” She closed her eyes.

Things jumped out of her mouth before she could sieve them, and though he never flinched, she hurt him.

“Do you like your superiority?”

She married a man at her level, and he was laying under concrete.

“Do you like my superiority?”

He never dated girls in his neighbourhood.

“Maybe. It tells me that if you are worthy, then so am I.” He confessed.

“Am I worthy?”

“To me, you are.”

“What is worthy?”

Kissing is foreplay, but between them, it was much more. A kiss was hello, it was sorry, it was wait, it was move on, it was I’ve missed you; pass me the salt, excuse me, repeat that, bless you, do it again, and it was goodbye.

Njavwa kissed Sara, and the kiss said let’s forget that.

“My mother chose the spelling without the H because she felt it was a more youthful, appropriate spelling. Now she regrets it–she thinks it’s why I have no children.”

“Sarah needs her Abraham.”

“You’re not much of a father, are you? Especially not one of many nations.”

“I prefer making babies unsuccessfully. It’s the trying that I like most.”

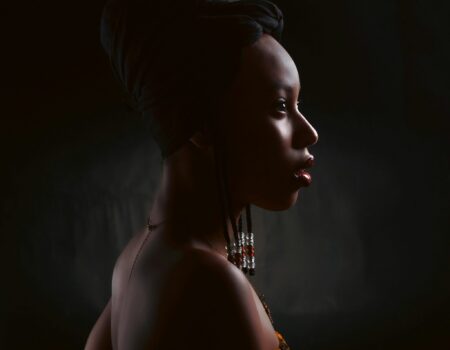

He fed his eyes with her body. No matter how many times he saw her naked, his mouth watered, and all he could think about was where he could touch, what he could taste. Njavwa thought Sara was well-made. She had a full head of black hair, bright white eyes, and a perfect row of ivory teeth. There was beauty there before the body wraps, keratin treatments, threading, waxing, and wispy lashes they applied at the spa. Sara was a pearl. She made him believe in natural beauty.

He kissed her inner thigh.

“Do you sleep with the others?” She asked.

“You’re a questionnaire today,” He flipped her over and smacked her bottom.

“You started it.” She mumbled into a pillow.

Once he was sure that she was relaxed, he laid his body on top of hers, delighting in their differences–hard meeting soft, smooth meeting rough, hot meeting cold.

“Do you care?” he whispered in her ear.

“Mhm.” The formless sound was all she managed.

“I have sex with them, but I only sleep with you.”

She writhed and resisted before submitting to their raw truth.

“It’s sad.” She said.

“What?”

“I am possessive of you but not Albert.” She said.

“Poor Albert. At least he is resting.”

“Because of us.”

Sara ached to hear Njavwa say that he belonged to her. That he was hers—that he would lie, steal, and cheat everyone but her—she stopped herself. It would be foolish to believe a lie standing on a lie.

“Are we bad people?” She asked.

“We are not good.” He concluded.

“Who are the good people?”

“People with simple desires.”

Mukandi Siame

Mukandi Siame is a writer and brand strategist. Her short stories Landing On Clouds and No Strings Attached were runners-up in the Zambia Women Writers Award and Kalemba Short Story Prize 2023, respectively. Her essay, Like Mother, received the inaugural Ubwali Hope Prize 2024. She contributes to Nkwazi and writes a personal newsletter called Kandi's Notes. She believes great stories can change the world. On Instagram & Twitter/X, she’s @mukandiii.