“After almost two months of walking and living off wild food or gifts from generous villagers, we reached the upper River Nile region, and there our problems multiplied…” An excerpt from page 69.

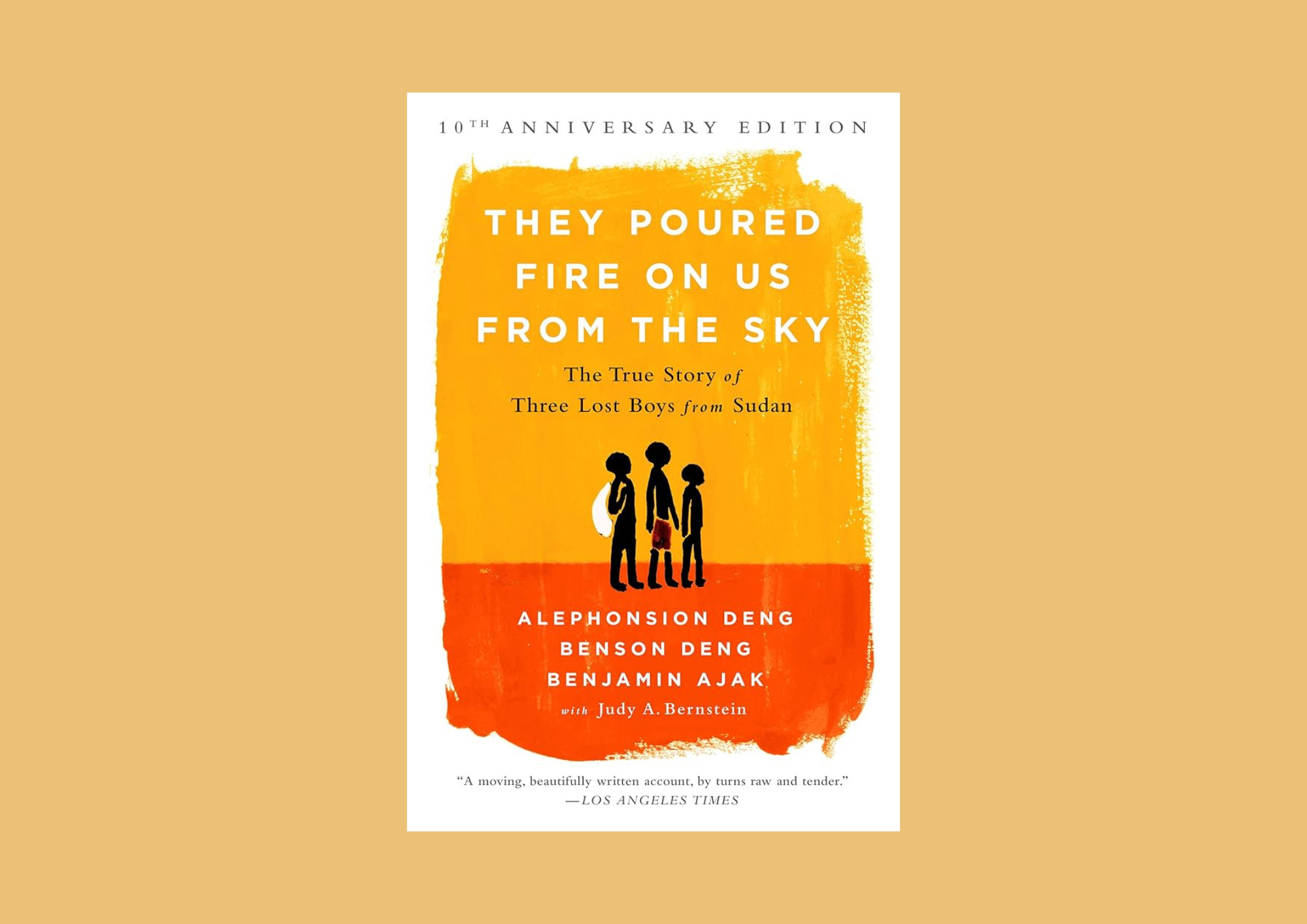

They Poured Fire on Us from the Sky is a memoir I found hard to imagine. it’s a story that left me thinking about life, and its troubles, thus leaving me with a change in perception of how I perceive life’s challenges. It’s a story that taught me the act of perseverance and endurance in weary times, told with a distinctive blend of Sudan and Africa’s history; it held me captive like a deer caught in headlights until I finished indulging my emotions in it. I’ve never read a book whose characters had such a first-class gripping war experience as this. It is beyond description.

This book details the life of the authors, Benson, Alepho, and Benjamin, and their experience with the 1983 Sudan Civil War. The writers are so skilled to start our journey from the onset of their lives in the village of Juol. They described how they once lived peaceably in their village rearing cattle, farming, and other kinds of rural lifestyles before they were suddenly visited by war, thrust to fled their land, driven out of their abode, and how it left them in shambles; as fathers couldn’t find their sons, and mothers lament the death of their daughters, everyone was left in agony, with majority killed, raped, sold to slavery, those who escaped had to fend for themselves and embark on a journey they are yet to know.

Fleeing the village of Juol for safety was a treacherous decision that led to different paths of regret, death, starvation, mental derangement, hostility, trauma, compassion, endurance, hardship, and many more. While I read the story of the authors and that of other boys, I couldn’t help but cry, especially getting to relate to the death of those innocent children who died in the course of the dangerous journey. I began to muse that these are children who know nothing about oil, race, or religion. Who couldn’t even define Sharia law, or had any issue with ethnical groups, they are just innocent ones who had only wished to live, yet were left to languish at the mercy of bombs falling on them from the sky, bullets, and wild animals in the wilderness. The account of the Murahilliins attack on the villagers, and the barbaric imposition of religion on people is an act that I think still kept many African countries in slavery, that some people in Africa aren’t yet convinced of the real definition of religion, it reminded me of the death of Deborah Samuel who was stoned to death and set ablaze over alleged blasphemy of prophet Mohammed in Northern Nigeria. A weird act that I consider inhumanely unbelievable for our current century.

Reading through the death of Alier, Achol, and Monyde brought me to tears, that I began to imagine how many boys had terrible stories like these people that we don’t get to read. Those whose stories were buried in the stinking mire of death. Those whose stories were swallowed up in the grip of flashing grief. Trekking a thousand miles across Africa’s countries and wilderness is nothing but a Hell on Earth experience. From Juol to the Ethiopia Refugee Camp, crossing the River Nile, my tribute to those boys who were swallowed by crocodiles. Their experience crossing the desert was extremely harrowing from every author’s point of view. The “Falling Down” chapter from Benjamin’s opinion caught me so hard. It sends cold, fearful shivers down my fragile spine. Considering their age, I couldn’t comprehend how these little boys could endure such a harsh hardship, at every point of their journey, with several near-death experiences that they had, yet, on their own, they strived, surviving by eating mud, and drinking urine, I couldn’t imagine how dreadful that would have been.

Alepho has a peculiar style of storytelling which to me sounds comical and sad. Scenarios of how people called him a stone head, and how he wrote that his legs were so tiny that he feared that it would break up in the lorry before they arrived their destination made me laugh, however, his style of writing is so emotional that I began to imagine if he had the most horrific experience among the other writers. I loved his writing around the death of his best friend, Achol. Benson, on the other hand, has a distinctive writing style; his vivid description and iconic representation of an African village made me paint imagery as I read each line. As an African, this brought me to imagine how brilliant Benson is with his words, he has a style that resembles that of Chinua Achebe, crafty, silent yet, harrowingly reverberating. His words have a dexterous way of leaving you gloomily moody. While I read some chapters written specifically by him, I was pulled in. The truth is, many people have great stories yet have a hard time penning them down, not everyone has the gift, but with Benson, I could feel everyone’s lamentation reflecting through his words, his words are like a voyage that conveys the agony of the lost boys’ story. His description of the death of Alier, and Monyde rawly reveals their pain that I had to wipe my tears through its gloominess. I would love to go back to Benson and learn some of his skills. He is a writer whom I admire so much.

I couldn’t help but bring my philosophical idea into reading this book. At first, I pondered the fact that no matter how hard a situation may be, those who will survive it will survive it, and those who would lose their lives for it, sadly, would. Alepho, for instance, slept among dead bodies, feigning dead. He’d escaped bombs and bullets, what a wise boy at his age. The same Alepho was visited by a Lion, the Lion sneezed on his face, and left him to kill another boy. Starved, vulnerable, how could someone trek thousands of miles barefoot? Surviving the scorching sun of the Sahara and the severe cold of the night without shelter. The death of his colleagues alone should have discouraged him and let him know that he would not survive, even old men and women died, much less a young, helpless boy. Yet in all, he was persistent, striving in difficulty. I learned from his uncommon steadfastness, I’d rather never give up in my life.

While poor Alepho was passing through those hard war times in Africa’s forest, he had no idea that a crown was waiting for him in America. Did he even know that he would write a bestseller off his story? I was pulled in, and several thoughts ran through my mind: why is it so? How about those who died in the forest of starvation, sickness, wild animals, and the Army’s bombs and bullets? I’ll continue to think about their treacherous journey over and over again. Poor Benson, too was met by a Leopard, yet he survived it; he had his bit of unimaginable difficulties, coupled with Benjamin’s description of people falling down. I was astonished to know that when you fall down, you don’t stand up again, it means you’re dead. Even though they were sick along the way, they still survived the hard way. I learned a lot from their story, and their sort of trouble is immensely inspirational.

There is much about this book for you to find out for yourself. There is a level of melancholy that you will be exposed to reading this book. It is the best memoir that I’ve ever read and it caught me endlessly seeking meaning. I’d love to consider this book as a thoughtful resource for the preservation of the history of Sudan and Africa at large. It expounds on the outdated techniques of circumcision in Africa and in the Sudanese culture. It also conveys the role that the International Rescue Committee and the United Nations played in the 1983 Sudan Civil War, and the question of whether there are any lost girls, and their possible story of survival. It is a historical resource for the story of the war in Sudan, the cause, and its brutal consequences on its citizens. I have many questions about this book that I wish I could get answers to. I wish I could write an elegy to mourn the souls of the lost boys who died in the course of the journey and those skulls that are unrecognizable, but I feared that my dirge would never bring back their lives. Tremendously harrowing and heartwrenchingly pulling, they poured way more than fire on them from the sky.

Peter Okonkwo

Peter Okonkwo is a UK-based Nigerian writer, journalist, publisher, creative director, classical musician, literary critic, editor, certified orator, and soon–to–be novelist of Etean’s Destiny. He was part of the 15 creative excellence individuals selected for Bristol’s BSWN CultureBiz Incubator Program, recognizing the significance of his outstanding works in the literature field. Peter is the author of seven poetry collections, a violinist who has played in orchestras in Nigeria and England, and a community founder of the Akure Book Club and the Akure Book Festival. His show, PEL, has featured over 1000 literary works, covering reviews and interviews from authors around the world.