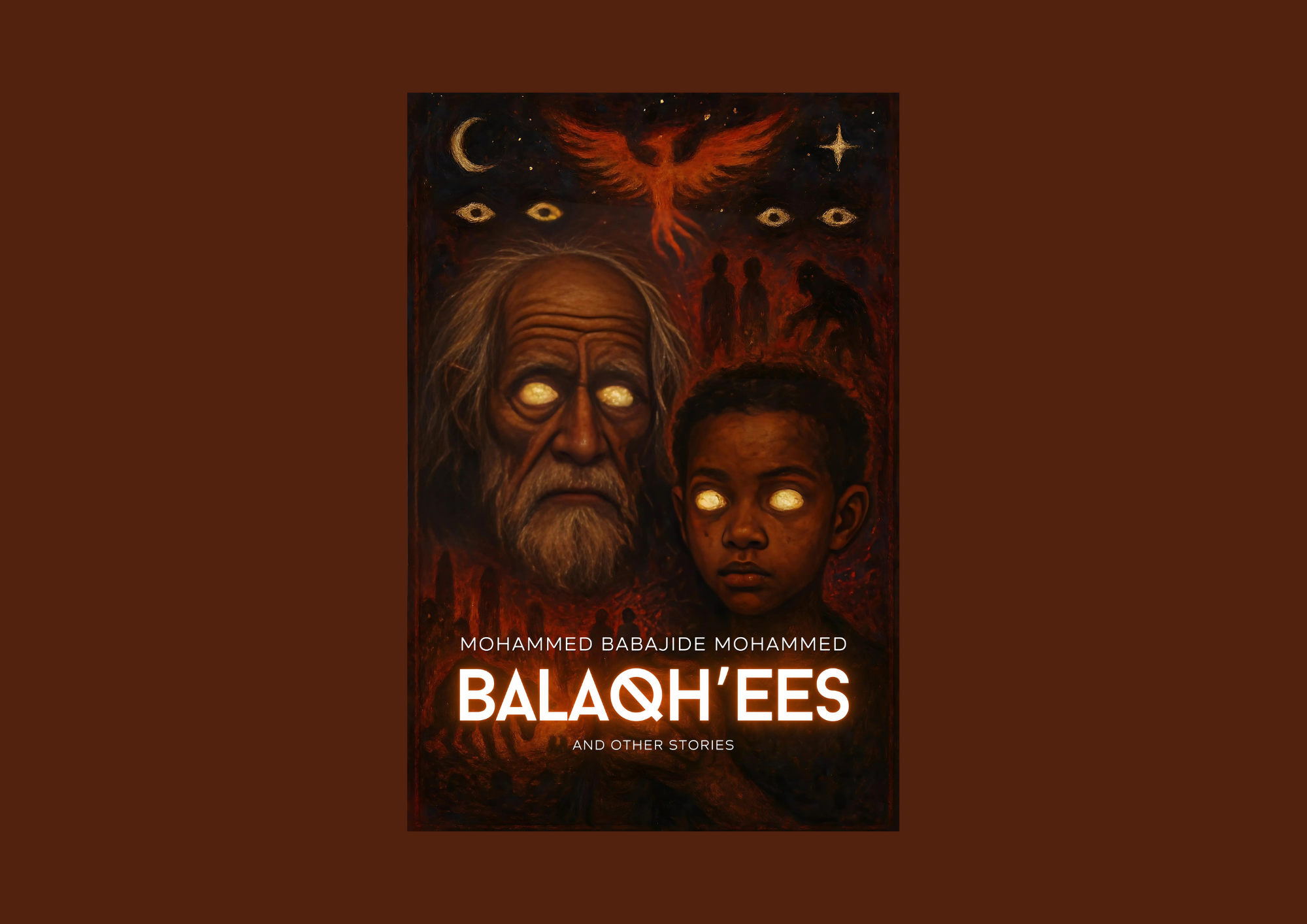

Mohammed Babajide Mohammed’s Balaqh’ees and Other Stories is a daring collection that refuses to be neatly shelved. Across eleven stories, he blends Yoruba folklore, horror, speculative fiction, and myth to create a book that feels at once rooted in tradition and unafraid of experimentation. It’s definitely not a comfort read, but the kind of fiction that unsettles, provokes, and insists you pay attention.

Touring through the stories, the collection opens with “Unhallowed Grounds”, where two students, desperate for wealth, strike a dangerous bargain in Atan Cemetery. Their greed leads them into a world of Alijanu and ritual, setting the stage for the book’s recurring concern with the costs of desire. Then we meet Thomas, a boy cursed with a living, whispering and evil face growing at the back of his head, and how it follows him from Romania into exile.

“Crossroads” reworks the age-old bargain-with-the-devil motif: a grieving lover begs for Ellanor’s life, but his deal grants him immortality with a deadly touch. “In A Traveler’s Dilemma”, dreams open into doorways across history, from ancient Egypt to the sinking Titanic, culminating in a companionship between two ‘Travelers’ who wander the boundaries of time and space.

At the collection’s center is “Balaqh’ees”, a sprawling, visionary piece that reads like a Yoruba-inflected Dantean journey. The narrator, guided by Reason and Wisdom, confronts landscapes of monstrous greed, half-buried corpses, and spectral judges. It is the book’s most ambitious story, pulling together its preoccupations with morality, fate, and the unseen.

Other stories explore memory, myth, and terror in more intimate frames: “Igi Osogbo” retells local folklore through the voice of Maami Eniola, “Heaven is Not Real” leads two brothers through a brutal revelation, “The Endless” imagines humanity shaped by parasitic beings, “The Seer” offers a meditation on longing through Damien Gray’s relationship with the sun, and “The Monster at the End of this Tale” cleverly entwines campus ghost stories with the oral warnings of childhood.

The strongest aspect of Balaqh’ees and Other Stories is its imagination. Mohammed moves fluidly between horror, speculative philosophy, and folklore, often within the same story. His images are vivid and unsettling: the laughter of the dead in “Unhallowed Grounds”, the parasitic revelations of “The Endless”, the grotesque whispers of “Thomas”. The collection demonstrates a keen ear for oral storytelling, particularly in “Igi Osogbo”, which reads like an intimate fireside narration.

Equally impressive is the book’s ability to weave Nigerian cosmology into universal themes. References to babalawo, Esu, and cultural prohibitions sit comfortably alongside European Gothic motifs and science fiction speculation. In doing so, Mohammed situates Nigerian storytelling as part of a larger, global conversation about fear, morality, and imagination.

Not every story land with equal force. Some endings feel abrupt, as if the story’s momentum suddenly dissipates just when it promises the most. “Crossroads”, for instance, delivers an excellent premise but resolves its central curse too quickly. In other cases, such as “The Endless”, the ideas are so large that they risk overwhelming the characters, who serve more as vessels for concepts than as fully realized individuals.

The book’s structure, however, is well considered. The stories move in waves, opening with horror, dipping into folklore, expanding into cosmic speculation, and closing with meta-reflection. This sequencing prevents the collection from feeling monotonous, though a stronger connective thread (perhaps a recurring voice like Maami Eniola’s) could have made the transitions even more resonant.

Well, this book is for readers who enjoy fiction that challenges and unsettles. I mean fans of speculative folklore, horror, and myth-driven storytelling. Definitely, any Nigerian who reads this book will find the cultural references deeply familiar, from the warnings about whistling at night to the rituals of the babalawo. But the stories are accessible to international readers as well, resonating with anyone who has ever been fascinated by the uncanny, the forbidden, or the cosmic.

Balaqh’ees and Other Stories is not flawless, but it is striking. Mohammed’s ambition is evident in every tale, and even where execution falters, the imagination behind it remains compelling. The collection demonstrates that Nigerian folklore can stand beside Gothic horror and speculative philosophy, not as imitation but as innovation. This is a book that deserves to be read, argued over, and remembered long after the final page.

Lydia Efobi

Lydia Efobi is a writer and founder of the Tutorluchi review site, with over five years experience reviewing books. With more than 100 reviews on Amazon, Goodreads, and Barnes & Noble, she helps authors reach readers through thoughtful, in-depth reviews and connects them with reviewers who can champion their work. She gravitates toward stories that weave together myth, memory, and imagination, writing about the books that resonate deeply with her. Lydia is most at home with a novel in hand, seeking out the kind of stories that linger long after the final page and shape the way she sees the world.