In 2017, tucked beneath the upper deck of my campus room bed, I wrote I have a tribute that stretches from my navel. The words, scribbled inside my Calculus II notes, would come to me within minutes of one other, like a string of sweat drops trickling down your stomach. Screenshots of Tryphena Yeboah’s untitled Insta poems sat beside me like a patient friend, approving of my ache.

all I’ve got to show for all these years are not even poems….

i have only to show my palms…

after years and years of carrying the pieces…

looking for a way to heal while I held on to you…

These words sat beside mine like students eager to learn from one another. All the while holding my hand through this mountain I had not addressed for twenty-one years, the loss of my daddy.

All around me, the usual mess of unwashed plates from the previous night’s takeout, a roommate blasting Victorious on her Dell laptop, and another animating a dance. Outside, an unsettling dusk had taken over, as if it were a soundtrack to my poem. I will remember in particular the feeling of suspension after I had written the last lines, my boyfriend’s text popping up on my second-hand IDEOS, the guilt of leaving this poem behind, the thrill of seeing him. Later, in an interview with a National Newspaper, I would refer to those Insta screenshots as among the many poems that hold my hand.

I turned twenty-two the day after that. That night, sitting on the ground floor cubicle of the boys’ hostel, 12 Years A Slave showing on my boyfriend’s brand-new Lenovo laptop, I would lament the lack of music in some scenes; how I had to sit through them without something to walk me through the tension. Each time I watch a movie, I remember that evening, the hum of the mosquitoes outside the half-open window, the silence in between the scenes, my boyfriend’s hands in my braids, mine on his chin, his recently trimmed beard scratching my cheek.

Whenever everything slowed down, and there was silence, shadows, and silhouettes in the movie, I would remember our family house in Turi at night, how the surfaces took on random shadows against the faint glow of our kerosene lamp. How, on the nights I was alone, they transformed into scarecrows, and I held my breath. With time, I would rely on the objects around me for distraction: my coloring book, the comic book with country maps, and especially the family photo album. In every photo of my daddy, he is rocking a cap, his features are a replica of my brother’s; his round face, his small mouth. Every time I looked, his eyes met mine as if they were building a protective wall around me. In one photo in particular, he is leaning against a blue van. There is a scar below his left eye. One time, while we worked on our farm, I sustained a scar on my forehead from using a garden hoe unsupervised. I would replay the sting, imagine he must have felt the sting the same way, and run my fingers over the photo, a way to ease this pain. In every photo without my daddy, I am there, a spitting image of Mami. In the only photos I share with my daddy, he is in a coffin, I am wrapped in shawls, on Mami’s lap.

When I turned ten, I visited his grave in Kwandege. I remember the darkness outside the bus window during the ride. Throughout the whole trip, I sat on my uncle’s lap with my coloring book, drawing shapes and then coloring them. I think now, of every time he dug into his jacket pocket for the color pencil I wanted a small act of kindness. Mami told me it was ok to call him daddy. Cũcũ said it was a Gikuyu tradition. He has a daughter named Nduta, after cũcũ, like me. And every time we called him daddy, he would answer to us as if he was not capable of distinguishing who was his daughter and who was not. Thinking now, he was the closest I could ever be to sitting on my daddy’s lap. But also, riding that bus with him, all I thought of was my grandparents. How cũcũ would clap for me when she saw me. Guka would complement the gap in my teeth and say I had grown tall. How uncle-daddy bought me dates and collected the seeds from my mouth. Even now, I remember the sweet, soft, chewy texture of those dates in my mouth and sometimes, cry at that memory.

There was a freshly weeded cover crop around daddy’s grave the first time I visited, and a bird pecking at something beneath the cross. When I visited again, the cover crop had dried. A considerable amount of dust had taken over. Whenever there was a whirlwind, I would study how the dust shuffled on his grave, and wonder if he was cold or warm. There were times I played with the dust, tried recreating the shapes I had learnt in class. One time, a rash formed around my mouth, my neck and hands. Cũcũ panicked. The nearest dispensary was a two-hour drive so Guka plucked a slice of aloe vera from the fence, smeared the gel on my neck, my hands, and on the area around my mouth. My grandfather repeated this ritual every day. Cũcũ boiled neem leaves for me to drink every day. I hated the sharp, bitter taste the water left on my tongue. Within a week, the rash was gone. But deep down, I believed the rash came because I had eaten the soil on daddy’s grave. So, I stopped visiting it. I would watch it from a distance, envy the birds that pecked on the soil, and the twigs that seemed to thrive.

I did not see my boyfriend much when I moved out of the campus hostel. In a WhatsApp text with him, he suggested a movie date where we could watch Chicago Fire. I did not want to watch it. “Why?” he asked.

In 2007, I watched our family house burn to the ground. The air was heavy with smoke. I was tired from sleeplessness. Rival tribes surrounded our village. Their presidential candidate did not win. My sister, bundled on my back as I walked, snored softly, her tiny hands clasped around my chest, unaware that the world around us was burning. We trekked the shortcut to a safe house, women and kids, guarded by men on all sides. The compound we were rounded up in stood on a low hill. I sneaked out, with my sister still on my back to go see our house go up in flames. The grey horizon turned a fiery crimson. I heard people scream from the valley. I heard women cry from all corners of the compound. I heard my sister snore. I did not see my mother cry. I cannot remember whether she cried, or whether she was among those who were watching the fire raze. A faded crescent moon hung in the sky; a mute witness to our anguish.

The next morning, we descended to our valley to inspect the rubble. I do not remember thinking of my daddy in that period. Two months later, I was in boarding school, but the violence had not died down. Each time I was out in darkness, all I saw in the sky was the fire, the sky turning red. The news kept reporting numbers: deaths, casualties, IDP camps, and relief food. My science teacher told me that Mami had moved closer to school—my cũcũ’s home. The message brought warmth, as if it put me closer to her. When it was dark, and I saw the fire in the sky, I imagined my sister snoring softly beside her, in her new room, and wondered if she had started to speak. I don’t want her to remember how we burned, I wrote in a poem.

There are so many other ways to remember that burned house; the 1998 cloth calendar that Mami was unable to discard, converted into a window sheer; the three giraffes printed on the light fabric, which made them capable of movement whenever wind whizzed through the cracks of the already ageing window; the 2004 calendar with a wedding invitation of some prominent political figure, the word VENUE printed on it, which caused me to interrogate my bitter-sweet relationship with pronunciation. Memories of Waweru Mburu flaunting his baritone on the day’s episode of Yaliyotendeka, over Mami’s cooking, over the slurred speeches of drunks on the road that led to Aldai, over the gong that rang to alert the Kwa Bernard farm workers that it was time to spray the last round of insecticide and leave for their homes in Turi, in Aldai, in Boror, Cheponde, Arimi, Tergat.

In my first essay writing class, Mr. Lawrence will write MEMORY on the chalkboard. In his exercise, we will close our eyes and imagine we are in a house. I will describe my memory of this house as one stained by its ash. I will describe the photos in the family photo album. In one, Mami sits on a stool on the steps, my auntie is doing her hair, and my elder brother is playing with the dirt. Mami’s hair is dark and long, or maybe the photo lies. Her cheekbones are low. She cannot be more than twenty-five here. Where is daddy? Has he died yet? Where am I? Am I born yet?

He will read my essay in assembly the next morning, pin it on the school noticeboard, and enter it for a primary school students’ essay writing contest. He will ask me what I want to be when I grow up, I will say, author. Every time I am at my reception desk, the corporate values of this consultancy firm I have worked for since my internship staring boldly at me, I will remember him pausing, his eyes widening, him leaning on the wooden twin desk and saying, “I see it.” I see it too, sometimes.

In every one of my primary school compositions, my daddy was there, an abstract painting I could not exactly describe. In the composition I wrote about my mother, which also ended up on the school noticeboard, I could not produce him explicitly. In every poem I have written after 2017, he is present like an ever-looming cloud. I ask myself where he has been hiding all those years. In 2021, I got the nerve to submit the poem that started it all, I have a tribute that stretches from my navel. Sarah James emailed me in January of 2022, saying she wanted to include the poem—which had been previously published in her online magazine—in a print anthology. The theme was contemplation: a long, loving look at the real. Could this mean that my daddy was finally beginning to have a real form?

When she first published the poem, she sent me a reader’s comment: You wrote of grief and made it beautiful. Maryam Hassan said of my poems: Nduta makes grief sound so sensual. In that bus ride with my uncle-daddy, I remember the warmth of my back against his thumping chest. In that memory, there was a shawl. There was a shawl because the weather was cold. Every time the shawl fell, he picked it and wrapped it around both of us. It is this kindness that I rely on in my poems to write about absence. My uncle-daddy is no longer with us. On the day of his funeral, I was fifteen going to sixteen. I watched his daughter cry for him; her plump cheeks, her coffee brown skin wearing sorrow like a second complexion, and a torrent of tears welled in my eyes. That was the first day I really cried for my daddy. Later in the night, the full moon’s glow fell on the fresh flowers we had placed on the grave. I wept into my hands. Their graves sit adjacent to each other. I usually joke and call them my twin daddies.

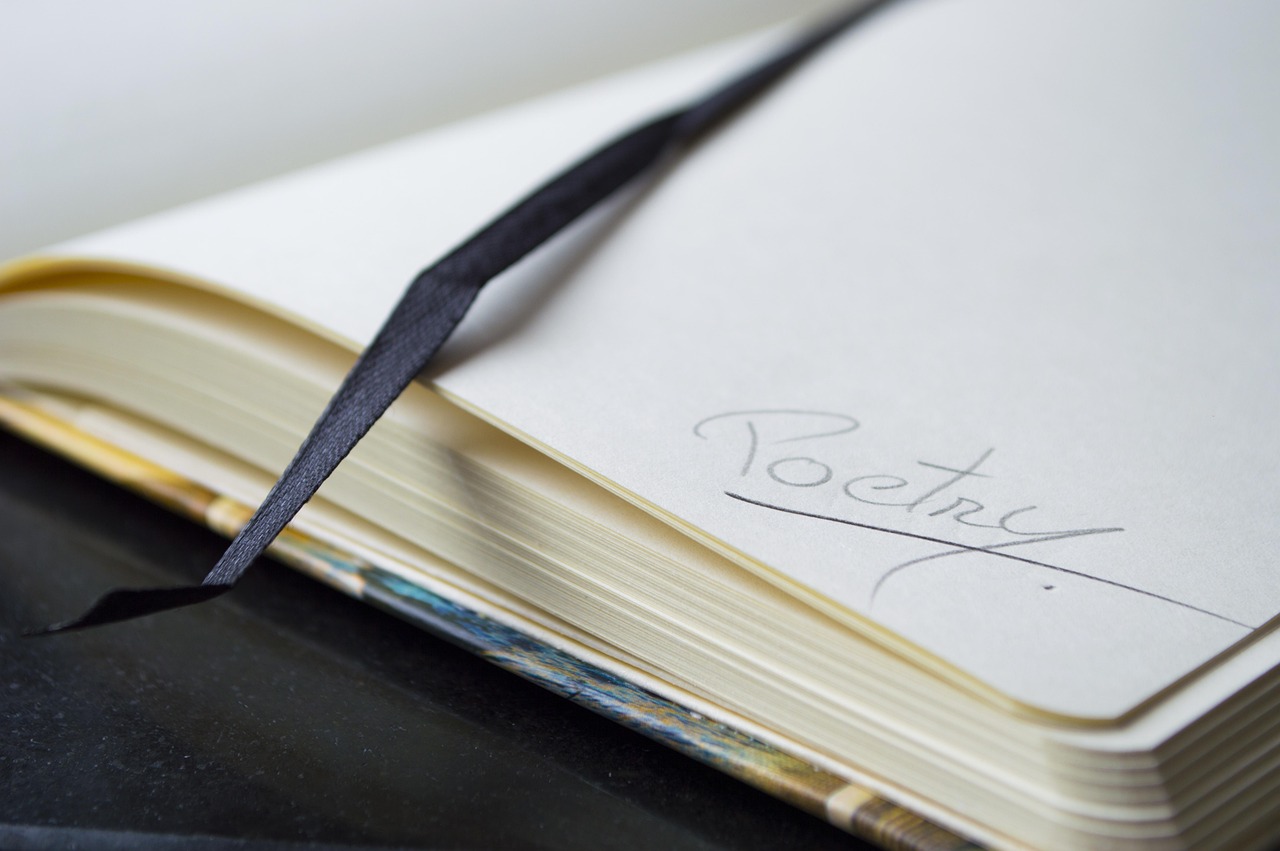

In 2024, I sat in an essay writing class, Building from Memory, with Kiprop Kimutai. He spoke of Rough Hands as a story of looking back; the death of his uncle sparked a memory. Whatever keeps coming back to your mind, Kiprop said, has meaning. After the class, I thought of the poems I had read over the years, the many lines that kept popping in my head randomly, and how they had helped keep alive the memory of my twin daddies. Over a period of four years now, I have maintained a tradition of writing these poems down. Cole Arthur Riley writes: Ritual, when coupled with beauty, makes for a very adequate mooring. It won’t carry you to shore, but it will keep you close enough that hope can swim out to visit you regularly. I am on my fourth journal now. The poems are holding my hand. There are poems in there I have trusted to help me speak to my daddy. There are lines I have read to him. There are poets in there I have trusted to keep him close to me. Samuel A. Betiku: Do you not house your father in you now? He isn’t gone. & like the apparent loss of the sun in one sky is a dazzling in another, there are stories in the expanse of your heart beyond what sinks in this place & its sombre air.

When I was little, playing with my friends on the banks of the river we nicknamed Shawa, I saw an antelope. I followed it until it disappeared into the bushes. In 2023, in a loss and grief class, the trainer told us that her daddy died after eating the meat of an antelope. It brought the image of the antelope I saw. The horns eventually caught it in the bushes, and the men slaughtered it. There was a feast. No one died, I wrote in one of the poems to my daddy. Does he know that I grew up into a published poet? Do my poems impress him? In the same class, the trainer asked us what grief we were trying to understand. That I did not see my daddy, I said.

Over time, posting my handwritten poems online would come to be a practice my followers looked forward to. My words were holding their hands as much as they were holding mine. It was through them that I came to meet Ken at the counter of Wasanii, waiting to enter the Auditorium for a play. He had read the handwritten poems I posted on my Insta stories, and the profile Frank Njugi did about the sense of place in my works. We had exchanged a couple of WhatsApp messages, and they all led to this moment. The vapour from the milkshake on my left hand was melting on my palm. A stick of cigar nestled between his index and middle finger like a delicate thing. The fingers of his other hand encircled carelessly a copy of House of Rust. A packet of Embassy was visible on the right pocket of his milk-white slacks. He offered me one stick and I declined. A photographer mistook us for a couple and offered to take a photo. I placed my right hand on Ken’s shoulder. His jaw was sharp when his head leaned towards mine, and the outline almost left a mark on my cheek. Later, smiling at my awkwardness in posing for photos, I would notice how his teeth were stained yet evenly spread.

Ken hated his job at a moving company. “I would rather be a full-time thespian,” he said. We talked about the sense of place a lot, and how, from reading my profile, Turi was a place he wanted to visit. Then, I realized that it had been fifteen years since I visited that place. Mami said the village people returned, erected new buildings to replace the ones that were burnt down, and resumed their lives. But she has not brought herself to wanting to return there permanently. My two daddies were not buried there and I am relieved. In that space of fifteen years, the place they were buried in Kwandege has three other graves—cũcũ and guka’s, an uncle’s.

Ken did not visit home, he told me. In the same year our house was burnt, he witnessed an assailant hack his daddy into pieces. He remembers his daddy. He loved rocking Savco jeans. He played the guitar in a local pub in the evenings, a gift he received from a settler whose farm he worked on, and he loved the bottle. My guka worked on a settler farm too, I told him. In my younger years, I would watch him tend to the cover crop on daddy’s grave, a knapsack sprayer strapped to his back. In the dry season, he would try to stop it from drying. During the rainy season, he would trim the cover crop as if caring for it was his way of loving his son. I wonder who waters his graveyard now. I have not been there since we buried cũcũ.

Ken cannot separate the image of his daddy being hacked from every other memory of him. He cannot visit his grave. He has three siblings. One flew to an Asian country for work when he was ten, and no one has heard from him since. His sister is in a correctional alcoholics facility. His mother fell into a deep silence when his daddy died. A goodwill organisation takes care of her. He pulled a photo from his wallet. On it, she was spinning him in the air. She was lean, her hair fell on the sides of her face like armor. Tryphena Yeboah, again, reigned in this moment of studying Ken’s mother: I have looked at my mother’s spine, and it looks a lot like a mountain of histories collapsing into itself. I cannot separate the poems about my daddy from the story of his. But he continues to be the abstract shadow that looms and breathes in my poems, that I cannot reach expliiitly and touch.

When we watched Karu Gakwa— a monologue about a mother who narrated the journey of bringing nine kids to this world in her kitchen — he expressed his love for kitchen scenes in movies. I told him of my obsession with poems with kitchen scenes. Bella Townsend: The kitchen is a room built for two. At least that is what I think…The light above the stove is meant to hum. Whenever I read the poem, I remember the kitchen of our home in Turi, Mami stirring a pot of uji, the firewood sticks crackling as they smoldered on, my friend Cira and I on the steps, and Mami teaching us how to spell the word Fredrick. My daddy was called Fredrick. Once, Ken was engrossed in a game of ajua in their large family house. His daddy came home drunk, and on seeing his son’s grown hair, used a pair of blunt scissors to cut it. After the shave, for which he cried terribly through, Ken dashed to where his mother sat in the kitchen. “She hugged me like I was a breakable thing. I cried like a small baby,” he said. He promised to never cut it when he moved out. It had been ten years since, and his locs were tied in a messy bun. Pieces of lint peered from a couple, and I was tempted to pluck them. I was envious of his ability to access his daddy, to access his memory as if reaching for an article on a shelf. His ability to dramatize him, characterize him, bring him close in a way that I could almost swear he is familiar. Sometimes, I cannot remember my daddy’s face.

I have two teenage sisters now. Their daddy is a teacher. I find, in my stories, a character who is a teacher popping up a lot. In two works in progress now, the main characters are teachers by profession. In Sanctum, the protagonist’s daddy is a biology teacher. The same in my story The Way Sundays End. I wonder now, were my daddy alive, how his profession would play out in my stories. Once, when I was little, my class one teacher passed on. We were in a file, fifteen of us, not four or five years yet, singing a song for her at the funeral. All I could remember was the day she pinched my thighs with a pen. I cannot quite recall what mistake I had made. But I remember the sting, and that I did not report to school the next day. I did not feel any grief for her. Every time I write about my daddy, as a way to grieve him, am I also processing all the small deaths that I did not understand enough to mourn when I was little?

Naomi Nduta Waweru

Naomi Nduta Waweru (SWAN XVIII) writes her poems, short fiction and essays from Nairobi, Kenya. Her essay, "The beacons. The Bearers of our Light", was listed in Afrocritik's 50 Notable Essays from Africa in 2024. She made the 2023 Kikwetu Flash Fiction Longlist. Her work has appeared in Lolwe, Agbowo, Orison Books, 20.35 Africa, Olney, Ubwali, Weganda Review, Poetry Column-NND, Down River Road, PeppercoastMag, Clerestory and elsewhere. She is a best of the Net Nominee, an alumni of the Nairobi Writing Academy, Lolwe Academy, as well as The Ubwali Masterclass of 2024. Reach her on Twitter and Instagram @_ndutawaweru.