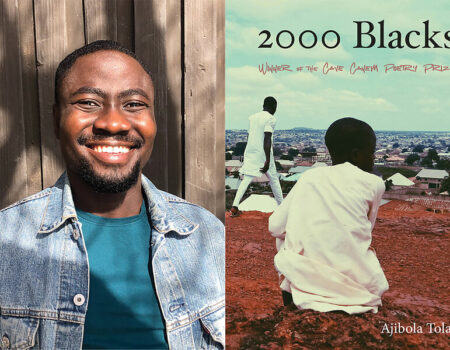

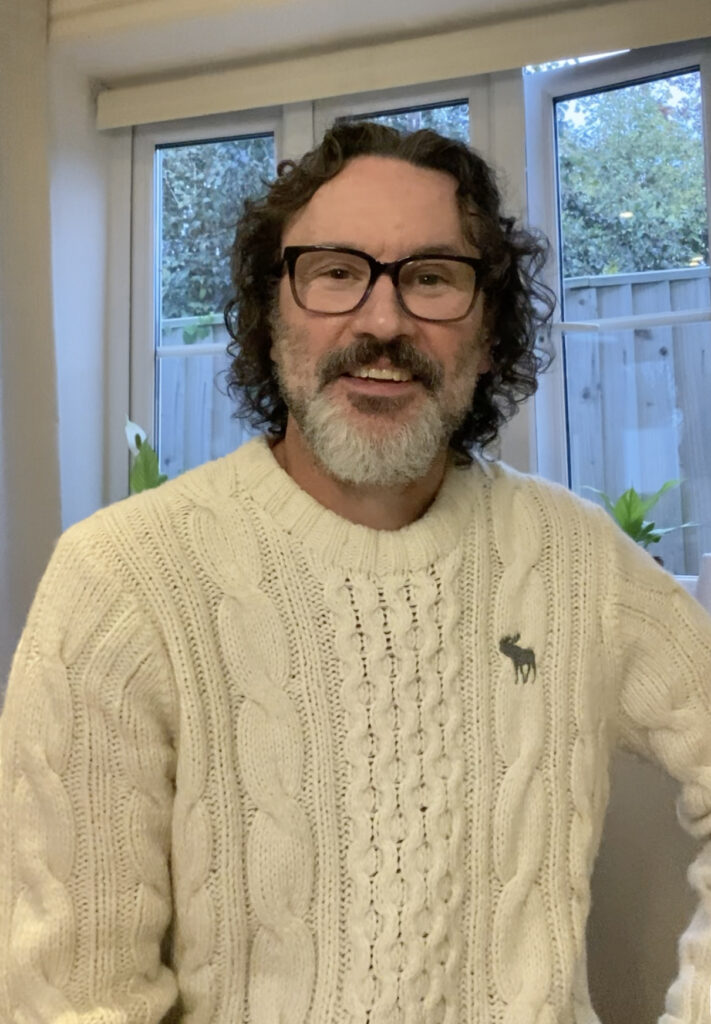

Stephen Embleton was born in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and is now a resident in Oxford, United Kingdom, since being an academic visitor to the African Studies Centre, University of Oxford in 2022.

Stephen was awarded the Best Novella by an African in the 7th Nommo Awards presented in person at Glasgow WorldCon in August 2024, for his Sauúti-based novella, Undulation. His background is Graphic Design, Creative Direction and Film. He is a charter member of the African Speculative Fiction Society and its Nommo Awards initiative.

His debut speculative fiction novel, Soul Searching, was published in the UK and US in September 2020 – and was shortlisted for the Nommo Awards by the African Speculative Fiction Society. His then unpublished YA fantasy novel, Bones & Runes, was published in the UK in February 2022. Stephen was awarded the James Currey Fellowship at African Studies Centre, Oxford University in 2022.

Stephen was recently awarded a literary grant by the Royal Literary Fund, recognising the literary merit of his body of work and literature-related activities.

In this interview, Stephen talks to Ibrahim Babátúndé Ibrahim about his journey from KwaZulu-Natal to Oxford, his many creative interests, how being a designer and filmmaker (among other things) influence his writing, and much more. Please come along for a beautiful and insightful read!

~

IBRAHIM

Welcome, Stephen! And congratulations on both your recent Nommo Awards win and your Royal Literary Fund grant. We’ll get to those shortly. First, let me ask. What does being a creative – poet, writer, designer, filmmaker – mean to you?

STEPHEN

Thank you, Ibrahim. Being “a creative” means continually discovering ways of expressing myself, expressing my experiences and my worldview firstly for myself, and secondly for others to see and experience in their own way. It also means putting yourself out there, which can be terrifying at times. And each of my creative outlets has different means for self-expression. I am grateful I have been able to be creative, and finding out who I am, and what I stand for along the way.

IBRAHIM

How do you marry all these roles, and is there one that trumps the others, or one that fuels the others, like the main creative source or essence?

STEPHEN

For a long time I felt illustrating was my main avenue for my creativity. Fortunately, I found writing, later than most skills, but a major creative form for a mind perpetually in inner dialogue. I continue to learn as much as I can with writing, writing as much as I can, and speaking with and learning from other writers and editors. This is how I have always approached my artistic skills: practicing, doing, learning, and experimenting as much as I can to become better and better.

IBRAHIM

What draws you to writing, to creating generally? How did it begin for you?

STEPHEN

Because I was always involved in visual media (drawing, designing, animating, filmmaking), I believed that was the only way my creative mind could be expressed. I properly “found” reading in my early twenties, and reading creatively written works showed me how I could paint with words, and this in turn sparked ideas which could only effectively be written. I can paint a scene with words in minutes versus hours with pen and ink! But I have never been confident in my ability to write well. And so I practise. I write what I have to, what comes to mind. I refine. I learn.

IBRAHIM

The Imagine Africa 500 is considered a very important piece of work in African literature, and this is where you had your first short story published in 2015, about a decade ago. Looking back now, what impact would you say that project has had on you and your writing journey?

STEPHEN

It had a massive impact on me on so many levels. It was the first story of mine published. Someone somewhere said this was good to publish. It meant I had something to offer. It was a deeply emotional piece, which made the acceptance even more special – that something introspective, philosophical, and simple in its narrative, could be published. That story, “Land of Light”, set the tone for everything I publish and rooted me and my heart in African narratives. It was published outside of South Africa, in Malawi, which meant two things for the future – my journey would not be insular (opening me to the rest of the continent), and most importantly it showed me the burgeoning African speculative fiction movement. I always say I have so much to read from the continent and the diaspora that I cannot keep up, let alone read international works. It also allowed me to grow my love and passion for the short story. Imagine Africa 500 opened my writing worldview.

IBRAHIM

Let’s talk about your process. Are you a pantser or a planner? Do you just go with the flow, or you’re one of those writers who plot and plan meticulously?

STEPHEN

Planner (to a degree)! I plot and plan as much as I can – but this comes after much thought on the initial idea, or the initial creative burst which sparked it off. Meticulous to a point. As I have learned with illustrating, you can spend years on the same piece, working and reworking. Plot in broad strokes. Write some scenes. See how it works. Plot some more, adjust. Ultimately, the story, when I get stuck in, can sometimes veer off despite my good plotting and planning. A character decides, nope, I’m going to do this instead. But my broad plot is there to rein me in.

IBRAHIM

Because your forte (from what I know) is mainly speculative fiction, I’d like to dive further into the importance of planning in writing. I mean, world-building is planning, isn’t it? And that’s the core of speculative fiction. How do you go about this? What does world-building mean to you?

STEPHEN

I find world-building essential, even in non-genre fiction. Ultimately you are setting up the time and place for the reader as soon as possible. Sometimes I only end up showing a fraction of the world-building to the reader, but the process, the massive amounts of research unshown, makes the world easier to write in. There are key areas I like to focus on, so it is important I find those areas I enjoy and use them to my world-building and storytelling advantage. The areas I find less appealing I spend less time in, but they are needed. Fr me these can be more technologically related. Networking with experts or writer friends who have these interests can also help where I may be lacking.

IBRAHIM

And in terms of content, what core areas are important to you… cosmology, folklore, anything else?

STEPHEN

Language. Living in South Africa makes you aware of English being a secondary language. English is common for general communication (and writing), but households, friend groups, they all speak other languages. I found, when I was writing, I was wanting to put in the languages that would be naturally spoken around me. Nowadays you can think of it like watching an international streaming show where we now have subtitles for the foreign language parts. You can’t really do that with an English book or story. So I’ve found ways of including it, to make it more natural, and by inferring meaning to the reader. It’s not to say I understand many languages, or write large sections of foreign language text, but hint at it, have fun with it. But give the people you’re representing on paper a truer voice. And with the range of cultures in southern Africa, cosmologies and belief systems have been fascinating since my late teens. What is it that makes a group of people function in certain ways? Family, social and political dynamics. For me these are then key to imagining a fictional place, a fantastical world, and the people who inhabit that landscape. Cosmologies give you beliefs, folktales, traditions, dress, food and language. Survival. Characters (and you and I!) are here in a story in a point in time because of everyone who came before them.

IBRAHIM

You’re also an editor. You were the editor of the 2023 edition of the posthumously published final novel of Flora Nwapa, The Lake Goddess. Tell us more about this.

STEPHEN

It was an honour to be part of Flora Nwapa’s The Lake Goddess legacy. The aim was to publish it in the UK, to give it a wider publication – which we did! My hand as the editor was with a light touch on the work, focusing on minor formatting, while ensuring The Lake Goddess was as Flora Nwapa as her family intended it. That book is a culmination of everything that came before in Flora Nwapa’s works. It is a boldness of ideas hinted at in Efuru. For me, it was different to editing works of people you can correspond with, collaborate with, and help craft their work. A unique opportunity.

IBRAHIM

This conversation would not be complete without mentioning the Sauúti Collective. You are one of the eleven African writers that make up the collective. Tell us your role in that. What you give to it and what it gives to you.

STEPHEN

As with all the founding members, I am one of eleven in a collaborative and inspiring collective. Each of us brings our unique worldviews, our strengths in our personal interests, and our willingness to keep building the world of Sauúti. I give as much as I can, as much time as I can, because I see the value it brings to us all, as well as the new creatives joining the fun of writing/creating in our unique world, and the readers resonating with the stories we continue to create. It has given me a supportive space in how we all share our ups and downs in our creative journeys – beyond Sauúti – and knowing others experience similar issues as writers. Bringing it back to the world-building: we share the load on interests, skills and knowledge in specific areas, where I’m not science and technology driven, others are and build those areas with us. Having some who are editors, gives you direct insights to better writing, plotting and character development. And inspiration: someone’s idea can spark another story idea for you. Sauúti is endless.

IBRAHIM

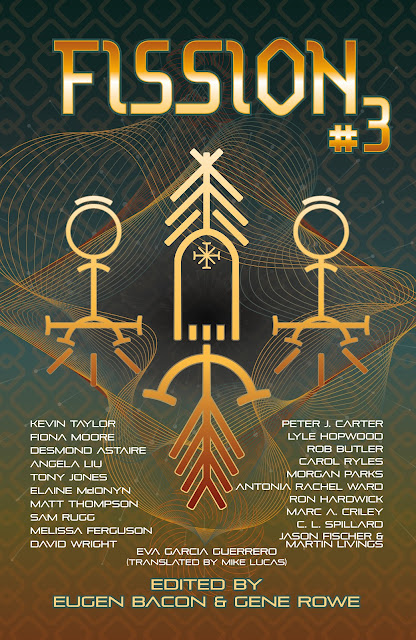

It’s not surprising to see you so enmeshed in such a pivotal project, especially as far as world-building and Afro-centric cosmology are concerned. I learned you designed the Fission #3 cover. How does your background in design influence your contribution, and your writing generally?

STEPHEN

I am always interested in visual aspects of people and stories. Sauúti in particular gave me the opportunity to illustrate some of the stories, visualise my own, and to a large extent make the written word “real”. Along with Akintoba Kalejaye, our visuals added another dimension to the world. One of the things which was essential to this, and how I look at any Afrocentric design and illustrating, is ensuring it is just that: Afrocentric. Even down to a city’s layout, clothing, patterns, they have to have that afrocentric conceptualising. I look at everything from the continent (which is endless and amazing!) for that real world inspiration. How have villages, towns and buildings been designed (not rigid perpendicular lines)? What are the political structures that have worked? What are the systems of written communication? In writing, these inform your descriptions and ideas of fictional places and their people.

IBRAHIM

This brings me to your illustrations, your Afrocentric fonts, etc. These are interesting. Please tell us more.

STEPHEN

My fourth year of graphic design studies I did a dissertation on typography (Cyrillic, Hebrew, symbology, type design and fonts, calligraphy, and barely scratched the surface of Middle Eastern scripts). Since then I have taken a more focused view of African symbols, patterns and motifs, iconography, alphabets and syllabary. Across the continent you have a vast array of unique “design” elements which inspire me in my own design and visualisations. To see so many African creators, and typographers, using these in their work, getting them out there is encouraging for our creativity. When I was studying, and with my early career starting in 1995, technology (and the emerging internet) had everyone looking to international designers and trends for inspiration. A few of us were thinking differently. In a 1997 interview I was quoted saying: ”A lot of South African designers should start going to their roots and design from Africa.” When I look at that now, I realise how that applies to all I do, including my writing. There is so much to create from and so much the rest of the world has yet to see.

IBRAHIM

I’m also interested in your background in filmmaking. Distant cousins, yes, but these fields are all still related. How related are they for you–in your creative works that is?

STEPHEN

It’s all storytelling. A single painting, a story, a film, all tell a story. I was glued to the TV since I was born, and films – the imaginary world – was always fascinating to me and more accessible than reading early on. Similar to comics. This is how I’ve approached many of my key scenes in my stories, from a filmmaking (directing) point of view. Even acting out some scenes! Getting into filmmaking helped me see more clearly structure, plotting, and writing. Working on predominantly documentaries, non-fiction, half-hour or one-hour films, was like working on a short story. Simple. Find the hook. Drive everything in that direction. It also gave me insight into how film and TV “publishing” works – much like literary publishing. The publishers view your “baby” as a commodity, and informed by trends, they figure out where it fits, or not, into their system at a given time. And that’s not easy to rationalise when you get rejections. Rejections always sting.

IBRAHIM

Coming from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, finding your literary voice there and coming as far as you’ve come, now residing in Oxford, England, how would you say your writing relates to place and how has it absolved your transition from place to place?

STEPHEN

I very much absorb my surroundings. I have always been inspired by the places and people around me. But I will always bring in what I know, those parts ingrained in me, the cultures I grew up with. It also provides me with a unique perspective. Back to filmmaking (and writing), when an outside filmmaker comes into a location, captures it in their way, and puts that into film, the locals then get to see it and themselves differently. The same goes with writing about a new place and people. Let’s see how that goes for me…

IBRAHIM

That brings me to your academic visitorship at the University of Oxford in 2022. What was the experience like, and how can younger writers also trace their steps to such lofty heights?

STEPHEN

Just write. At no point were the “lofty heights” of Oxford ever on my radar. I’ve only ever wanted to get published and to earn a living from my writing. Focus on writing and being a better writer. Be willing to talk about your writing. Be willing to collaborate and put yourself out there, not for yourself but for how you can work in building up others. Oxford was a lot of hard work (the hardest I’ve worked in literary circles) in a small space of time. It was enormously rewarding and beneficial. It showed me what being in the diaspora is like, looking back at where I come from and where I find myself now. It also showed me firsthand how the outside world views African literature, and it emboldened me to continue to nurture, support and champion African literature and most importantly, our writing community. Getting anywhere in literature is a struggle, and I want others to get that support to be writing and not barely surviving.

IBRAHIM

Among other things, you recently won the Nommo Awards for your Sauúti-based novella, Undulation, and recently received support from the Royal Literary Fund. How would you say these awards, recognitions, and supports impact your work?

STEPHEN

Like getting a story submission acceptance, to get your work recognised in any way is an amazing feeling, and inspires you to keep going. And I need to be writing! The Royal Literary Fund is an amazing support from the literary world for two reasons: taking my body of work into account and its literary merit out in the world, and taking some of the strain off of having to do other things to survive. The past few years I’ve needed to do extra exhausting work to help us get by, and the purpose of the grant is to alleviate just that so that the writer can write. It is such a good feeling. Writers struggle to make ends meet with writing, and we all need reminding that we are not alone.

IBRAHIM

Your first novel, Soul Searching, debuted in 2020, followed by your sophomore, Bones & Runes, in 2022. Is there a third in the works? What can you tell us about it?

STEPHEN

Yes, I am busy with a third novel. It is set nowadays in Oxford, and it brings my worldview to this strange place. The broad plotting is done, the characters are taking me into interesting places, and the research is all things I love: history, folklore, language and a dash of murder.

IBRAHIM

If you weren’t writing, editing, designing, or making films, in an alternate world that is, what other things could you have found fulfillment in? Surprise us please (laughs)

STEPHEN

If I had the patience to learn the finer art of woodwork, I could see myself making wooden furniture (chairs and cabinets) in the Arts & Crafts movement or Art Nouveau styles. Design, hands-on shaping, creating practical objects. These art movements continue to have an impact on my design and illustration.

IBRAHIM

Is there an emerging writer out there who’s impressed you recently – someone whose work you’d recommend for us to all look out for?

STEPHEN

I always look forward to work by Somto Ihezue. Generally shorter fiction, his writing is wonderful to read. Another whose work I’ll look out for is Shingai Njeri Kagunda. African speculative fiction is thriving, giving us brilliant writers to read and keep track of. Find them and read them!

IBRAHIM

What is the best writing advice you’ve ever gotten? Something you wish you had known earlier as a young you just starting out as a writer?

STEPHEN

Write! I didn’t listen to my English teacher in Standard 6 (Grade 8) when he gave me top marks for an essay I wrote after being inspired by Cannery Row (Steinbeck) – the first and only time I wrote like this in school! He actually called me aside and said it was impressive. I didn’t follow through because I didn’t think writing was for me. I started writing later in life, which is also good. I take the same approach to anyone who wants to draw, wants to create, and wants to write…do it. Don’t wait to be good at it. Don’t wait to be a writer to write. If you can put ink or paint or words on a page (or screen or device), you can create. Write. Write again. And again.

IBRAHIM

Thank you very much for your time and honesty.

STEPHEN

A pleasure, Ibrahim. I hope some of my experiences are useful. I am grateful for all the opportunities I’ve had and will continue to have, and being able to share any insights from my journey. For those writing, or wanting to write: write!