A poet’s father dies. She is tormented, and her world fractures into fragments of memory, longing, and sorrow. From these shards, she writes her debut chapbook which does not merely depict grief but embody it, shifting between rage and quietude, longing and release, devastation and rebirth.

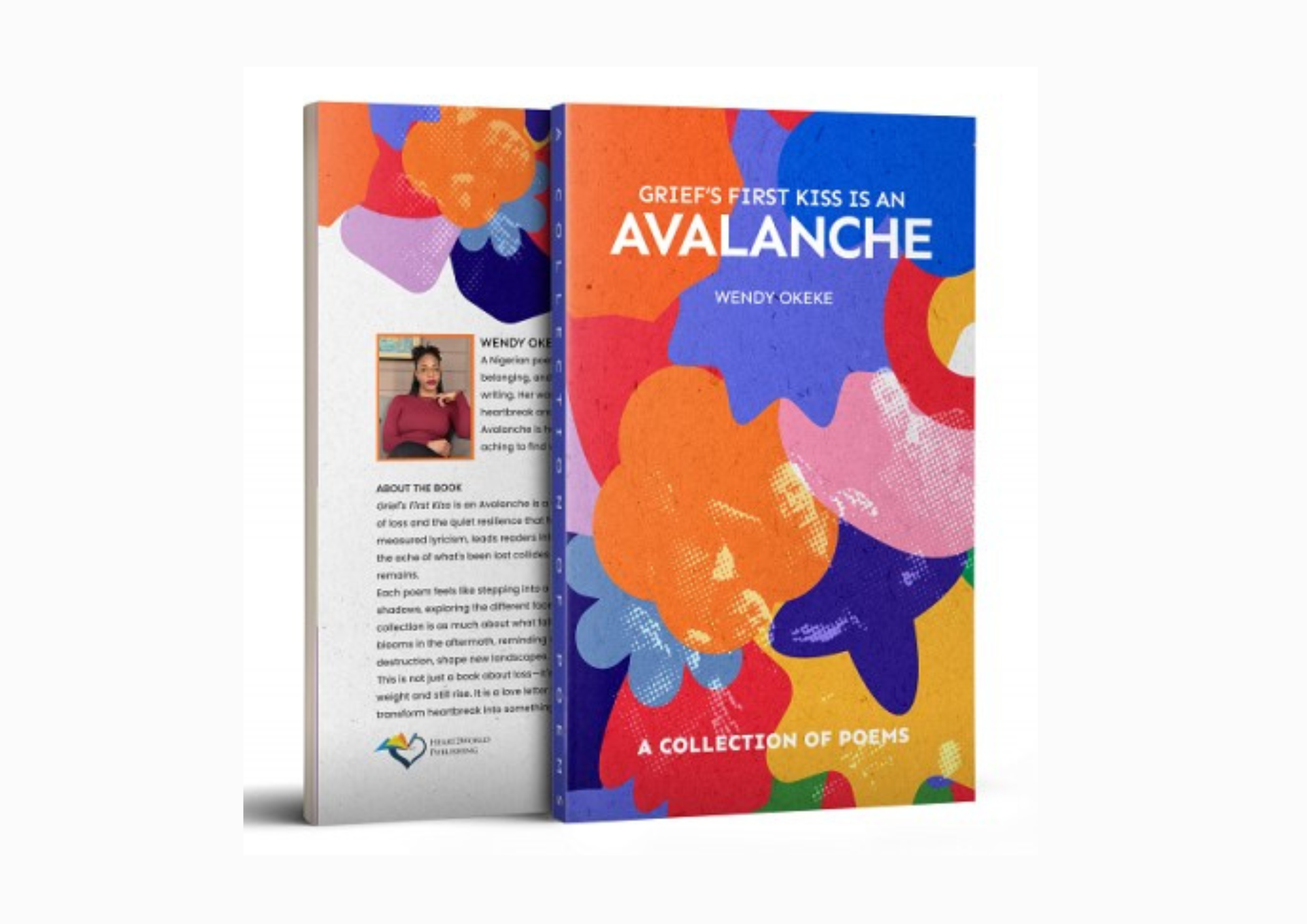

Grief unsettles language, distorts time, and fragments reality. Often, it does not follow a neat trajectory but instead reshapes and bends the self, as captured in Wendy Okeke’s debut chapbook, Grief’s First Kiss is an Avalanche —a moving poetry collection that gives form to loss, the weight of absence, the fragmentation of memory, and the slow reckoning with sorrow. For Okeke, grief is “alive” and it “alters perception,” as she shares in her 2022 interview with Nigerian News Direct. Her debut chapbook, written in mourning for her father, illustrates the contradictions of mourning as something both visceral and intangible, something the body carries and negotiates daily. Yet, the collection does not attempt to resolve grief; rather, it allows it to exist in its natural contradictions—suffocating yet illuminating, deeply personal yet universally familiar. The fractured syntax, fluid imagery, and shifting tones allow the poems in the collection to unfold like scattered memories—some vivid, some elusive, all haunting. Grief is portrayed as both an unbearable weight and an intimate companion and the collection dwells in its messiness, its unpredictability, and its permanence.

Okeke’s chapbook is a collection of 16 poems, that each uncover different experiences of mourning, loss, love, and grief. The poems are suffused with an intimacy that feels raw and controlled, making the reader a witness and a participant in the poet’s experience. From the very first poem, the reader encounters the most striking aspects of Okeke’s poetry: her ability to render abstract emotions into tangible, sensory imagery. Using the five senses, Okeke expresses tragic experiences with unpretentious poetic narration, ensuring that grief is not just felt but also seen, tasted, smelled, and touched. She uses colours as a visual language to project the shifting nature of mourning. “A Toast to a Man Who Always Lifted My Spirit”, the first poem in the collection, project the shifting nature of mourning in a colorful rendition. The greydry walls of the room, the yellow warmth of the family’s embrace after the tragedy, all capture the feeling of loss. She writes:

…sometimes, I settle/ into the orange feeling that/my father is my deepest loss. She goes on to say that …I am mostly red, swelling with rage—just knowing my father’s absence.

This color-coded plotting of grief is heart-wrenching.

The connection of grief to sensory perception extends beyond sight. The sense of taste is projected in “Hide & Seek”, where she asks, …what do you know about the ashy taste of longing; the sense of smell is evoked in “Grief is My Favourite Language”, where she laments, …your skin smells like whiskey and sadness; and the sense of touch is intensely illustrated in “Yellow for My Warmth”, as she confesses, …my bruises form a map on my skin/ each night, I trace their edges. This deep engagement with sensory details creates an immersive experience that allows grief to be felt in the body, not just in the mind.

The Language and Tone of Loss

Okeke’s language is deliberately fluid and rhythmic, often blurring the line between personal lamentation and a familial/collective act of mourning. The poetic language is at once intimate and detached, raw yet polished, fluid yet fragmented. Her diction oscillates between the everyday and the lyrical, demonstrating the mundane and transcendental nature of grief. At times, her poetry is direct and confessional, like diary entries. In other moments, Okeke embraces metaphor and surreal imagery to convey emotions that cannot be articulated plainly. Her syntax reflects the unpredictability of grief. Sentences break mid-thought. Some poems bleed into each other while others are stark and alone, mirroring the isolation of loss.

The chapbook’s language resists closure, leaving gaps that we, as readers, must fill with our own experiences of grief. The tone fluctuates between despair, nostalgia, anger, and tentative hope. For instance, in “I Am a Place”, the voice is hauntingly melancholic, heavy with the weight of absence:

“who are we today?

the ones earth has betrayed.”

Yet, in other pieces, the tone shifts toward defiance. There is rage—not just at death, but at the silence that follows it. In “Reckless”, the poet resists the world’s expectation that grief should be quiet or dignified. The tone is sharp, unapologetic, demanding to be heard. The mood of the collection mirrors these tonal shifts. Some poems are suffocating, evoking a feeling of drowning in sorrow. Others are open-ended, offering glimpses of light even in darkness. This interplay that allows both the heaviness of grief and moments of relief coexists side-by-side prevents the collection from being one-dimensional, making it a more compelling exploration of loss.

The Architecture of Grief

Grief’s First Kiss is an Avalanche embraces fragmentation. Many of the poems lack punctuation, projecting a feeling of breathlessness, of thoughts unraveling without control. Enjambment is used extensively, pulling the reader forward, refusing them the comfort of a full stop. There is no single, uniform structure. Some poems are tight, compressed, and bursts of emotion. Others stretch across the page, their form, a mimicry to the disorientation of grief. This structural variation reflects the nonlinear nature of mourning, where emotions do not fit into a neat progression.

The collection does not follow a rigid chronological sequence but instead oscillates between past and present, memory and reality. This fragmentation replicates the mental disarray of grief, showing how time collapses in the face of loss. A key narrative technique Okeke employs is the shifting of voice and perspective—sometimes speaking directly to the lost loved one, other times reflecting on their absence from a distance. This push-and-pull dynamic between the self and the lost other reflects the conflict between mourning and acceptance, between wanting to move on and being unable to.

Essential to note, throughout the collection, the body is the primary archive of pain. In “Body Language,” it is used to navigate desire and loss, while in “Reckless,” the body is a place of fear and self-destruction. In “Bloom,” the poet claims “the scars of the earth rise back from what has been lost”, linking the body metaphorically to the land, suggesting that trauma is cyclical, both personal and generational. Okeke writes grief as not just an abstract emotion but something felt, worn, carried. The poet’s body is a site of grief. In “Falling Forward,” she writes:

“Loss and hope share my ribs now,

Holding hands where breath used to be”

Memory, too, is central in the collection. Okeke does not narrate grief in a linear fashion but in flashes—memories that appear unbidden, colliding with the present. This disjointed recollection mimics how mourning unfolds: the past intruding upon the now, refusing to be neatly categorized. Thus, what makes the collection compelling is its refusal to offer neat conclusions about grief, love, or healing. Instead, it presents these emotions as fluid, unstable, and full of contradictions. Okeke is paradoxical throughout the poem. She writes about grief as both a presence and absence, of love as both salvation and pain, and of faith as both a comfort and a lie.

Okeke presents grief as something tangible, as in “Grief Is My Favorite Color,” where it becomes a physical weight in the air. Yet, at the same time, grief is framed as an absence, something that leaves the speaker hollow. The contradiction here: Is grief something we carry, or is it something that leaves us empty? The poet does not resolve this tension, and instead allow both interpretations to exist simultaneously.

In “I Consider Being Fucked by You a Type of Storytelling,” intimacy is rendered as a kind of sacred act, with lines like “we move like a hymn rewritten for two.” However, love is depicted as a source of suffering and self-destruction in “Yellow for My Warmth,” where a woman endures abuse and metaphorically transforms her wounds into poetry. This presents another paradox as the poet questions if love heals or harms, or if it does both simultaneously.

In “Threads of Grace,” spirituality is depicted as a source of guidance and solace: “She lifts us—torso to feet, pulling us from the quick sands of despair.” Yet, in “Yellow for My Warmth,” there is skepticism toward religious salvation, as the speaker states: “the priest speaks of heaven. I laugh, low and bitter, because there is none.” The poet does not definitively answer whether faith is liberating or misleading; rather, she lets the contradiction stand unresolved.

When deconstructed, breaking apart the language to reveal the underlying assumptions in the text, Grief’s First Kiss is an Avalanche does not seek to define grief, as well as love and faith, as a singular experience, but rather exposes its multiplicity, its contradictions, and its resistance to linear resolution. This is what makes the collection so compelling: it does not seek to “heal” us but to mirror our wounds back at us, asking us to sit with our grief, rather than escape it.