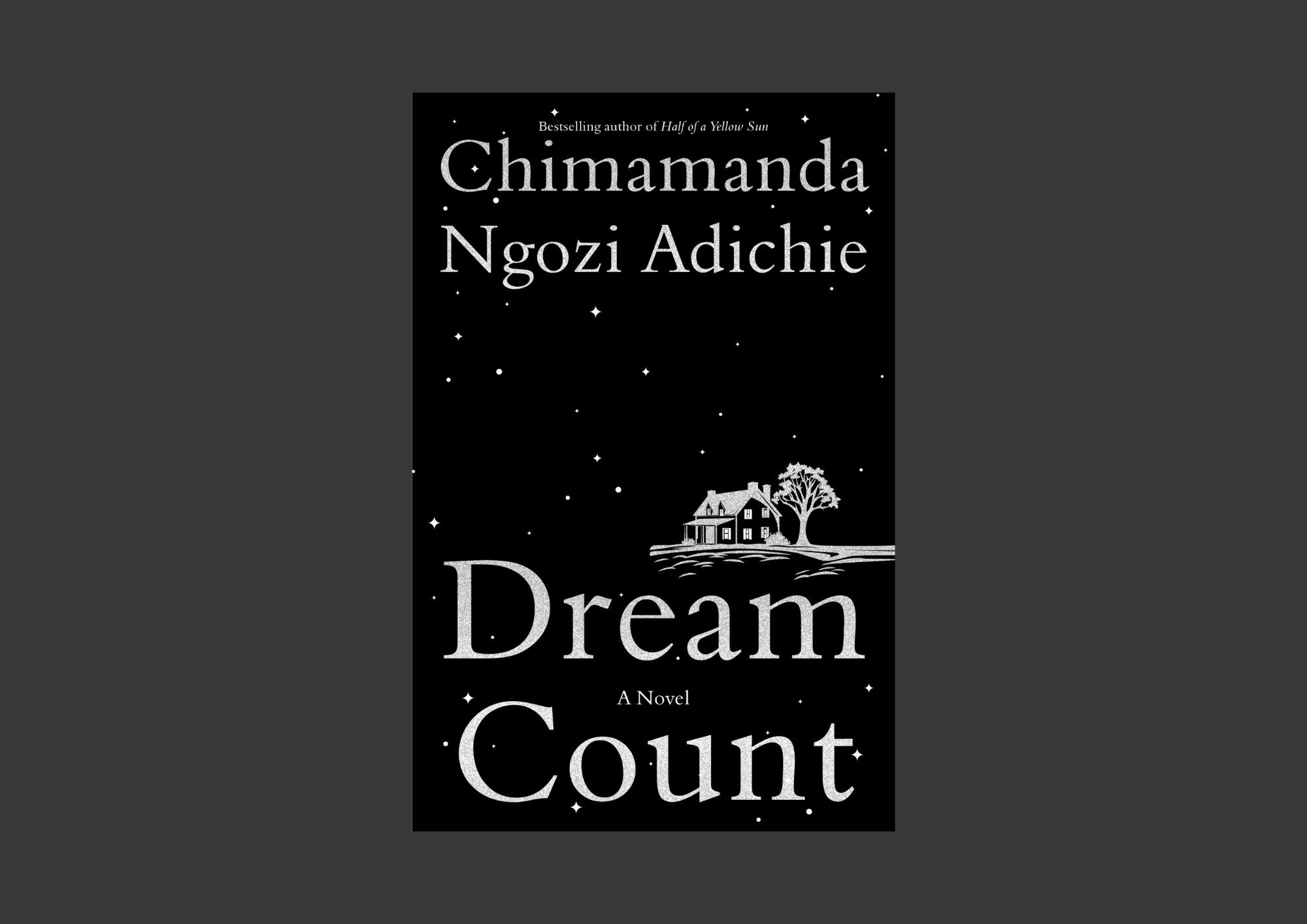

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s latest novel, Dream Count, features four female characters, each with a distinct story centring around familiar staples such as race, religion and culture in America as seen from the social worlds of migrants from her Nigerian Igbo ethnic group and also from Guinea Conakry. With migration as its social foreground and the COVID 19 pandemic depicting the force of nature in human affairs, the reader is thrust into the minds of women to understand the basis of practical choices they make or are forced to make against the ideals of their cultural orientation. One implication for the critical reader is to decide whether the Global North is a haven of safety for self-realization or a space for deferred dreams. The reader must also decide whether the novel is Adichie’s way of urging people to live before they leave.

Chia, the daughter of a wealthy Nigerian, is confronted with the major challenge of becoming a writer and finding a suitable male companion. After a bout of failed relationships, the self-enclosure and introspection that the COVID 19 pandemic made inevitable taught her that there is more to life if you are alive. So, she takes what seems to her a better path of travel writing and deferred the dream of marriage. Zikora, the goal-oriented lawyer, faces the same dilemma of choosing between the ideal and the practical. She has been taught that anything outside the given family pattern of her Catholic faith is not ‘proper’. But when Kwame walks out from their relationship shortly after he learns that she is with child, single motherhood becomes her only option. For Kadiatou the Guinean, something always seems to go wrong when she is about to snatch happiness from the venomous jaw of life. In one such incident, a prominent man assaults her sexually after she is settled in what she considers a comfortable hotel job as a chambermaid.

Kadiatou is clearly a fictionalised Nafissatou Diallo, the Guinean immigrant who made headlines in 2011 when she accused Dominque Strauss-Kahn, the then head of IMF of sexual assault. Omelogor, the last of them, is fiercely intentional and assertive. She has mastered the craft of professional banking to the point of beating her male bosses in their games and becoming indispensable to the institution. As she penetrates the innermost circle of Abuja society, she assumes a Dickensian role of unravelling the complicated life of elite urban women. Her strength and resilience fail her, however, when she is unable to get her acts right in her study of pornography in America. Embedded in the narratives are accounts of unreciprocated love and repudiation in which men and women are simultaneously victims and victimizers. In the portraits, Adichie seems to point to the fact that for women, success must not be tied to their relationship to men.

Faced with various challenges, each character reacts by wavering between the ideals of their social orientation and the demands of actual existence. While Chia and Omelogor are assertive and non-conformist in matters of marriage and career, Zikora and Kadiatou are somewhat fatalistic. Zikora’s single motherhood is a happenstance that she grudgingly accepts. Kadiatou flows uncritically and lives with her experiences of female genital mutilation, marriage, relocation to the U.S. and a dubious fame arising from her sexual assault. This contrasting character constellation is deepened by Adichie’s use of first and third-person narratives. With Chia and Omelogor as narrators of their own story, the author demonstrates the agency of narrative power in the portrait of women’s condition. She seems to suggest that the first place to start in the pursuit of any desire is assuming the captainship of one’s boat. This is not the case with Zikora and Kadiatou. Their stories are told in the third-person, subsuming their personalities in the social orders that seem to cause them pain by insisting on conformity. These are similar portraits we have seen in Mariama Ba’s So Long a Letter (1979) and Zaynab Alkali’s The Virtuous Woman (1987).

In Dream Count, the inner lives of the four female characters and their struggles with social expectations, individual desires are hamstrung by the realities in their homelands in Africa. The opportunities and challenges that America also offers to them are all brought out in vivid relief. This is a novel in which Adichie deeply engages the readers on the value of women making the best of what is available while working or hoping for better options. In the end, Dream Count does not take a stance, but raises critical issues and conversations. As one character puts it in capturing the tension between being and becoming, “[s]ometimes we live for years with yearnings that we cannot name. Until a crack appears in the sky and widens and reveals us to ourselves…” In other words, the reader is invited to reflect on the chasm between dream and reality. It’s more or less like saying to someone, “this appears to be a road, but I am not sure if you should take it or not.” Dreams matter, but living is a personal decision.

This review is based on the edition of Dream Count published by Narrative Landscape Press in Nigeria. I am curious to know if there’s anything in this version that differs from the one published in the United States.

Catherine Nkulume

Catherine Uchechukwu Nkulume is a graduate student at the Institute of African and Diaspora Studies, University of Lagos.