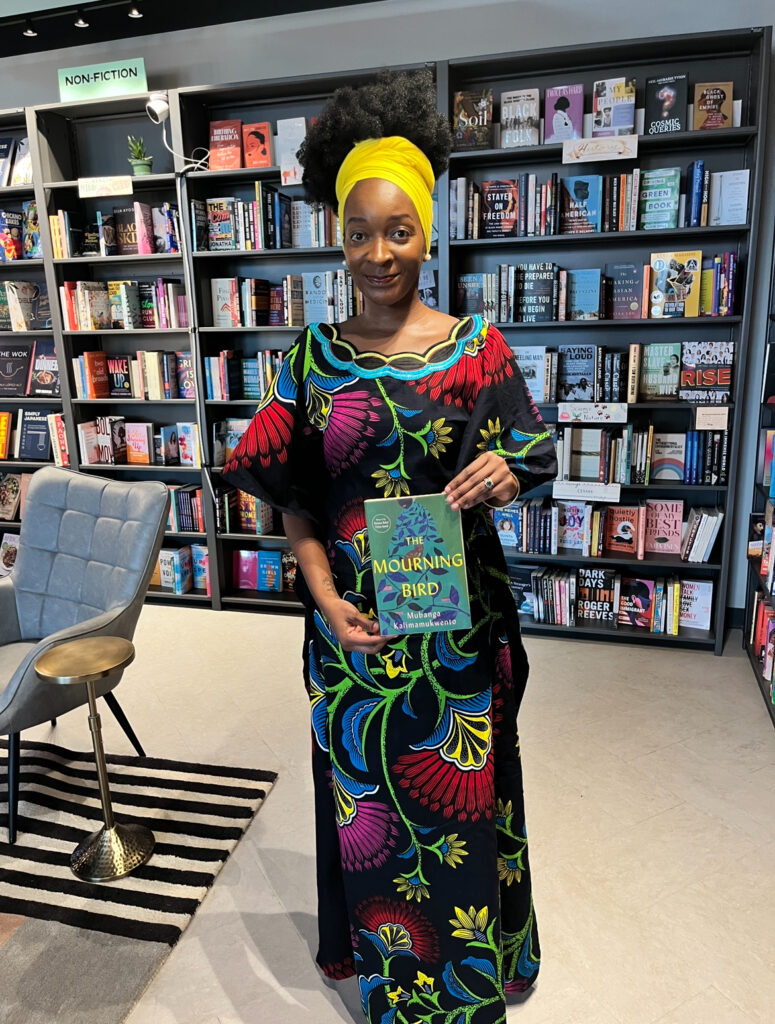

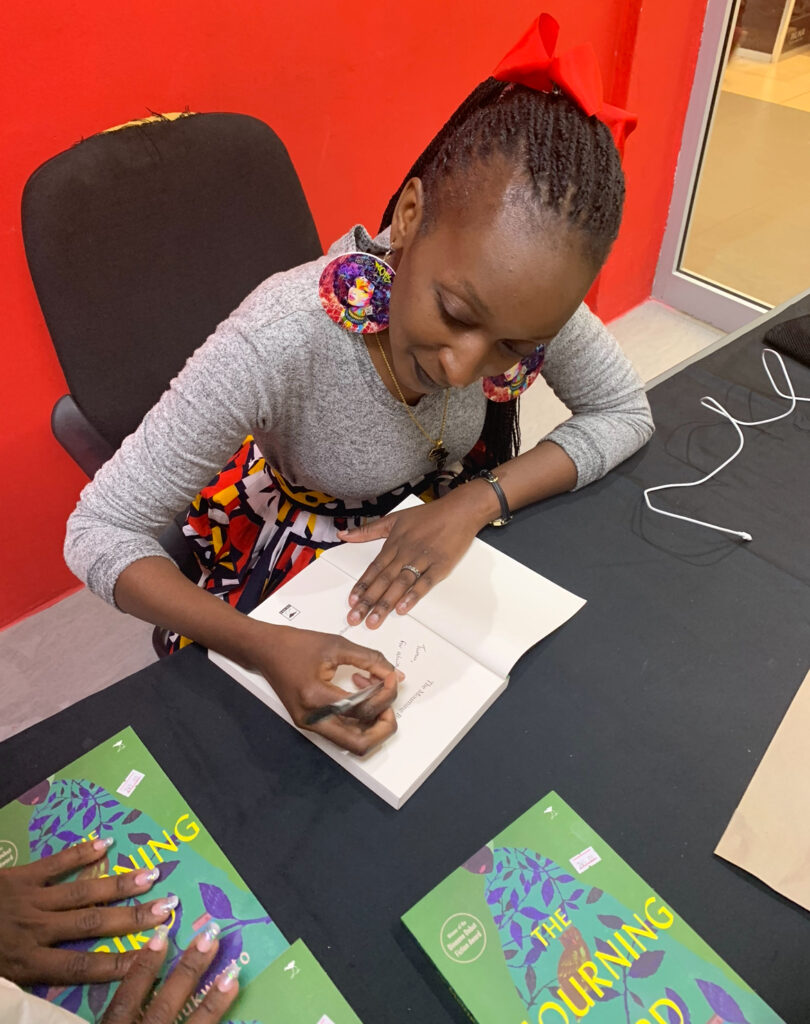

Mubanga Kalimamukwento is a Zambian attorney and writer with an MFA from Hamline University, where she received the Writer of Color Merit Scholarship and the Deborah Keenan Poetry Scholarship. She is the winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize (2024), selected by Angie Cruz; the Tusculum Review Poetry Chapbook Contest (2022), selected by Carmen Giménez; the Dinaane Debut Fiction Award (2019) & Kalemba Short Story Prize (2019). Her first novel, The Mourning Bird, was listed among the top 15 debut books of 2019 by Brittle Paper. Her work has also appeared or is forthcoming in adda, Aster(ix), Overland, Contemporary Verse 2, Passengers Journal, Menelique, on Netflix, and elsewhere.

Mubanga has been on shortlists for the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics (CAAP) Book Prize, Commonwealth Short Story Prize, Bush Fellowship, Miles Morland Scholarship, Minnesota Author Project, Nobrow Short Story Prize, Bristol Short Story Prize, & the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. Her work has received support from the Young African Leadership Initiative, the Hubert H. Humphrey (Fulbright) Fellowship, the Hawkinson Scholarship for Peace and Justice, the Africa Institute and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

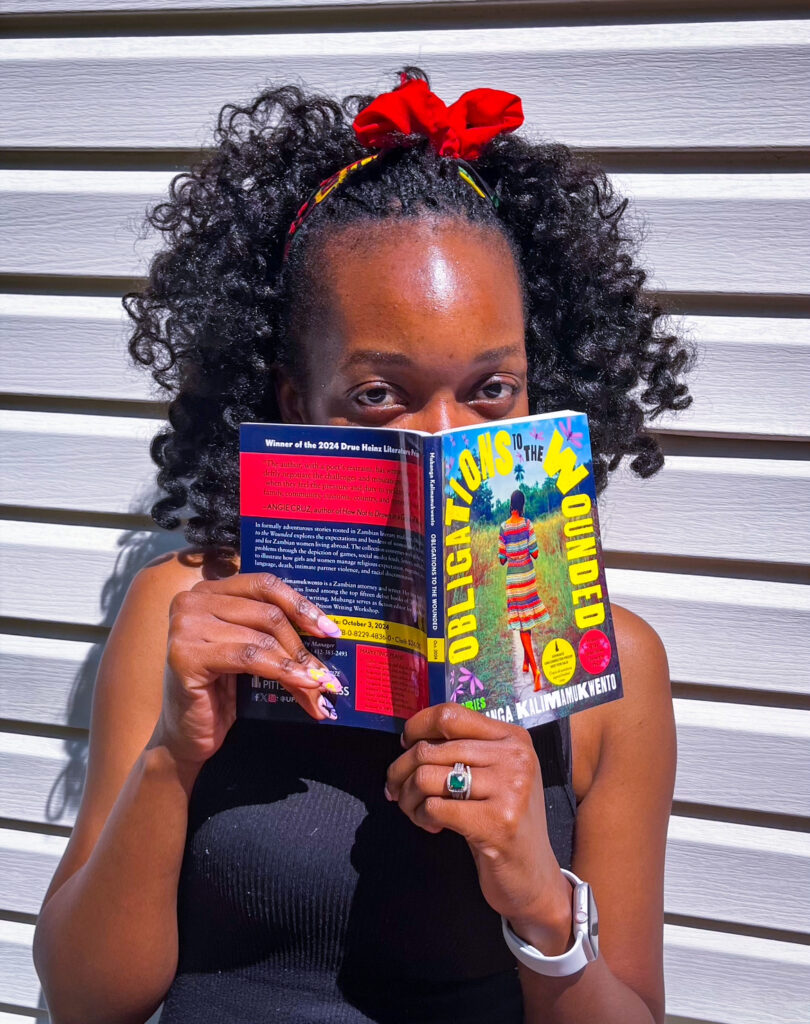

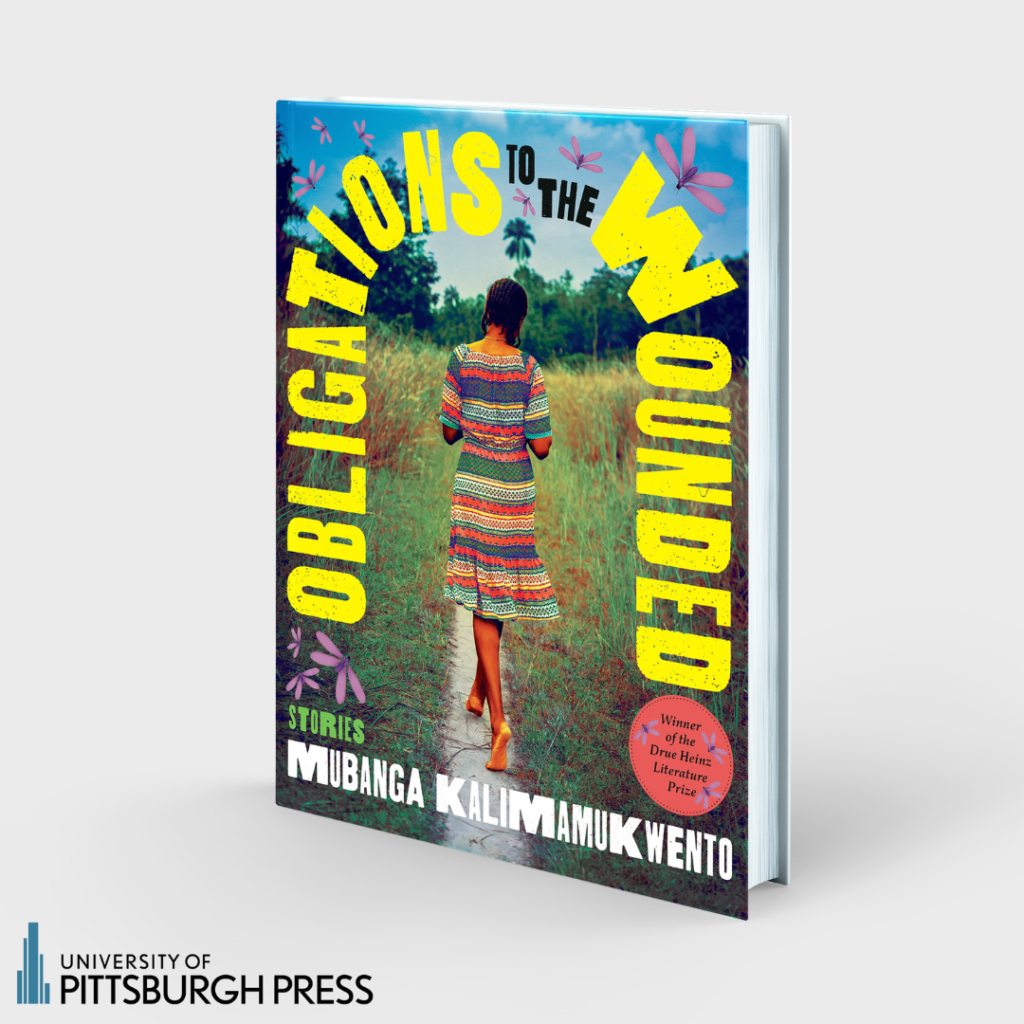

When she’s not writing, Mubanga serves as editor for Doek! and a Mentor at the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. She co-founded the Idembeka Creative Writing Workshop, is the founding editor of Ubwali Literary Magazine, a current Miles Morland Scholar, and a PhD student in the Department of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, where she is also an Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change (ICGC) scholar. Her debut collection of stories, Obligations to the Wounded, is forthcoming from the University of Pittsburgh Press.

In this interview, Mubanga discusses her writing journey with Ibrahim Babátúndé Ibrahim, touching on issues like rejections, what it takes to succeed as a writer, the MFA, the state of African writing, the ideas behind her Ubwali Literary Magazine and The Hope Prize, and much more. We hope you enjoy the insightful interview as much as we did putting it together!

~

IBRAHIM

Hello Mubanga. Thank you for joining me for this interview. You’re a lawyer. You’re a PhD candidate. You’re also regarded as one of the brightest stars in Zambian literature today. How did writing begin for you?

MUBANGA

Hi Ibrahim, thanks for having me and for your generous words. Zambia has so much literary talent, and I am glad to be living in a time when we, as a country, are becoming more visible.

My earliest memories of writing are from the year I turned ten, just after my mother died.

IBRAHIM

But why writing? Why not something else?

MUBANGA

Why indeed. When one is ten and faced with three deaths in two years, one must do something or else lose their mind––my something just so happened to be writing. Of those losses, losing my mother hit me the hardest. I didn’t have, in some ways, still don’t, have the vocabulary to explain it. But in hindsight, I can say with some confidence that I was trying to hold on to the pieces of her that I had.

It started like this: by the time she left, I was already in love with books because she had been in love with books and kept me surrounded by them, so I associated stories and storytelling with her. I was a very talkative child, and often, when my mother came from work, she would hand me a newspaper and assign me the task of completing the crossword to keep me quiet for a while. That crossword appeared on the same pages as ads and obituaries. After she died, I kept the crossword habit and became a little more curious about the obituaries. For hours after school, I’d pour over these lives, compressed into the classifieds section, and after a while, without really thinking about it, I began spinning stories out of the names I found there.

At the time, my classmates and I were in the habit of creating keepsakes called Autobooks––I think the ‘auto’ is taken from an autograph or autobiography, I’m not sure. Anyway, they were a little like DIY yearbooks. Each of us had a notebook we passed around the class and took turns filling up with tidbits about ourselves and cut-out pictures of our favourite musicians. I wasn’t popular, so my autobook was never full. In the blank pages, I started to create stories, using those obituaries as prompts. I imagined some of those people liked TLC, like me, playing their hands at raffles, like my mother, having their hair plaited, like my sister, and fried fish and chips on Saturday mornings like my Dad.

I was desperate for what had been before my family splintered, so I wrote. I didn’t know I was writing fiction and never showed anyone, but it was cathartic and kept me on this side of sanity for a while. That’s my writing origin story.

IBRAHIM

That’s quite an origin story. You’ve published a novel—The Mourning Bird—and you recently won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize with your collection of short stories—Obligations to the Wounded. Which is your preferred medium of storytelling, the novel or the short story?

MUBANGA

To read, I love short stories. Until a few years ago, I only read novels. When I started reading short stories, the immediate feeling was one of awe at how much could be compressed into such a small space, and essentially, my journey into short stories was a desire to replicate the magic I felt when I read shorts. Still, my entry into writing proper was the novel, so that is my first love. I relish the room I have to wriggle in a novel, the time to reconsider what I thought I knew. I enjoy revising and witnessing the story surpass my initial idea. The novel can sometimes be tiring and sometimes overwhelming, and I need breaks during which I write poems and short stories.

IBRAHIM

How do you approach either one? Are you a panster, a planner, or you’re somewhere in between?

MUBANGA

It’s different for every piece. Occasionally, stories will come to me whole, in a dream or something, and when I pen them down, they are exactly as they should be. I love that––how luxurious it feels to create something just right the very first time. Those are my favourite stories. Those are the exceptions, though. In general, I’m a planner, especially when I’m writing a novel. I have found it to be my sure way of never experiencing blocks. When my imagination isn’t giving me what I need it to, I can revisit my old self and follow her lead until the words are ready to pour out of me again. But it ebbs and flows. Even in novels, some chapters come willingly, and others I have to fight before they reveal themselves. There are pieces that I honestly just let free flow. My Miles Morland Scholarship-winning novel is proving itself to be like that––because it’s also out of my comfort genre, every day this novel shocks me.

IBRAHIM

How do you know when a story is finally done—ready?

MUBANGA

Cliché, but I just know, which isn’t really saying much because I have been known to edit right until the editor says, “Okay, we are going to print now,” and because of that, I avoid reading my work after publication unless I have to do a reading or something. I don’t want to see something and think, Shit, I should have changed that. Because I am constantly learning how to express my ideas better, even something I published yesterday will seem to me as if it still needs to be improved. That full stop moment is hard to pinpoint but depends on the individual work: usually, I find it by reading the entire piece out loud, hearing versus reading reveals places where a piece needs work, and my test is, if I can read it from start to finish out loud without pausing to correct, then it is done. What ends up happening when I’m facing an imminent deadline, is I click send while crying and hope for the best.

IBRAHIM

You’re a serial winner of literary prizes and recognitions. How would you describe the significance of winning, especially for emerging writers who have probably never won before?

MUBANGA

I had to sit with this one a little. I can see how it looks that way because all my longer-form publications have been ushered into the world on the wings of a prize. In my eyes, I am a serial submitter. I couldn’t even tell you how many pieces I have on submission in Submittable right now. My other habit is to delete rejections on sight. As in, the second I read the email, it’s gone. My email filters even know that. The first year I was shortlisted for a Miles Morland Scholarship, the email went to my spam folder because I had been rejected twice before, and deleted the emails. But because I am a serial submitter, I receive a lot of rejections.

People see the wins, but my laptop’s delete button is doing overtime. The Mourning Bird was rejected literally 100 times before it won Dinaane. The week before I found out I won the Tusculum Review Poetry Chapbook Prize, I got a very long rejection from another journal detailing all the things the editor hated about my collection. I was on the verge of pulling it out of every place reading it when the congratulatory email came. As for my Drue Heinz win earlier this year, that was my fourth entry.

There are things I have won on the first try, but many of the wins are a product of dusting myself off (editing) and trying again. This is the lesson: You have to have umupampamina, just be a little bit relentless and a little insane, and keep working on your craft. It can be maddening, applying for prize after prize, publication after publication, and sometimes seeing the same names over and over. Still, the thing to do is to keep writing and, if publication is what you want, to keep submitting. Eventually (sometimes after 100 rejections), something gives, and you are in an interview, floundering your way through a question where Ibrahim is calling you a serial winner.

IBRAHIM

(Laughs) What would you say is the singular most important contributor to your rise as a writer—a supportive community, mentorship, literary wins, workshops/fellowships/residencies, MFA, something more personal/innate, something completely different, etc?

MUBANGA

Writing has been the most important thing. Before the community, mentorships, wins, fellowships, the MFA––during, after––I am a writer, so I am writing.

IBRAHIM

Many veteran African writers frown on the seeming effects that American MFA programs have on African writing. In contrast, a lot of younger African writers see these programs as a lifeline for their writing, one that is essential for building a viable career as a writer. You are a product of that MFA system. How do you reconcile these differing lines of thought?

MUBANGA

I don’t know if you are calling a veteran writer the way my children say I am from the older generation or if I am the young writer of your question. I wouldn’t call myself a product of the MFA system. I went into my MFA with my first novel already published, so I don’t know that I considered it essential to build a career rather than just another opportunity to learn. I sense that what they (we?) are criticising in the MFA system is what can happen to your voice if you don’t guard it jealously during the program. While undertaking mine, I was often the only Black student and almost always the only African student. Before that, my community of writers centred our narratives on Africa. We came from different countries, lived all over the world, and spoke more than two languages. When reading one another’s stories, we understood that the work would be just as textured. The year I started my MFA, I had just joined Doek!’s editorial team. I worked with writers who eased in and out of English, Afrikaans, and Oshiwambo. My job, especially with the debutante writers, was to show opportunities for context that invited readers, such as myself, deeper into the story and not to ask them to pause at every turn, explaining themselves as if they were on an episode of Mind Your Language. Writers educated within at least the Zambian educational system will understand this, being able to engage with a text while understanding that you weren’t the author’s primary audience. I thought everyone knew this.

But then, in one of my first MFA classes, a classmate asked me to do more world-building because my story opened with a setting that seemed other-worldly to her. That place was Lusaka, Zambia, where I’d lived almost my entire life. What was every day to me, she categorised as speculative or fantastical. I had to decide quickly if I would be the peaceable student who took all feedback and sieved it in private and vented to my friends instead of speaking up during the class. Thankfully, our workshop model didn’t insist on my silence, so I spoke up for myself. That was an important lesson for me, and although it took me a few beats, I audibly rejected that feedback because it was asking my work to over-explain itself even when the context cues were there. In High School, the available books depicted stables and landscapes I couldn’t even imagine, but I knew that just because they didn’t exist in my mind didn’t mean they weren’t real. So, in an environment where you might be told, sometimes subtly, that your reality isn’t the norm and it must bend itself to be seen, one must be cautious not to betray oneself and graduate as a different writer than the one they are at the core.

That said, a lot of good things came out of my MFA years––I was exposed to the editorial experience I wouldn’t otherwise have had. I met incredible mentors, some of whom remain friends. I was pushed to write outside my comfort zone. I wrote my poetry chapbook, unmarked graves, as an end-of-semester assignment in poetry. I don’t know if I would have done that unprompted or if I would have even read the collections I was required to read, which is to say that there is good in most things. If I could have studied for an MFA in Zambia, maybe I would have, but such a program did not exist when I lived there, and I wouldn’t have been able to afford it anyway. This is true for many African writers in Africa who are looking for the kind of immersive writing environment an MFA can offer. To say to them, Don’t do it, it is bad because of XYZ, from this side of the experience, without providing matching solutions would steal an opportunity from them. Mine is to say, Do it if you want, but know this. It’s just that by the time they accept you, you likely can already learn what they will teach you in other ways.

IBRAHIM

That’s quite insightful. But in general, I suppose this is related to the talks of imperialism in the reward system available to African writers due to a lack of adequate infrastructure on the continent. You do some awesome work with Doek!. You also recently founded Ubwali Literary Magazine and The Hope Prize, both of which are great contributions to that needed infrastructure. To what degree do you agree with the imperialism claim, and how do you see African writing building from where it is at the moment?

MUBANGA

It stems from the fact that the funding––the fully funded MFAs, the bigger prizes, the ones that give you room to breathe, the fellowships––are financed by non-Africans, and the money decides what to value, what is good. Of course, that means specific authors and certain narratives will be valued over others, and as a writer, one must decide if they will honour the story they want to tell and let the money come to them or if they will bend. Ultimately, it’s about what escorts you into your dreams at night, whether there is peace in that space for you or not. You and I, Ibrahim, know there is inadequate infrastructure on the continent. That’s why you’re doing what you do at JAY Literature. We have both jumped through hoops to be squeezed into a chair at the table, so we are now trying to build our own tables, contributing to an ecosystem that will outlive us by centring ourselves, our people, our stories. Those are the projects I try to align myself with.

At Doek! we are intentional not just about supporting Namibian writers, but supporting first-time authors. That’s a model I tried to echo at Ubwali Literary Magazine. First and foremost, Ubwali is a Zambian magazine; each section honours Zambian artists first. It’s the same spirit with which the Idembeka Creative Writing Workshop, which I co-founded with Frances Ogamba and Kasimma, was formed. At Idembeka, we only accept work from African writers living in Africa with three or fewer publications.

IBRAHIM

I should mention that you’re also doing great work with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. But let’s talk about Ubwali Literary Magazine and The Hope Prize. Tell us the inspiration behind these very bold steps and what plans you have for them in the long term.

MUBANGA

Ubwali Literary Magazine is a dream I have had for so long but haven’t always had the funding and time to execute. An opening was finally available late last year, and I took the plunge. It’s still pretty scary, but the feedback I get, especially from our first-time authors, makes it worthwhile. For us, it’s not just about publishing them but about teaching them in the process, so that it is a little easier for them to get their work out into the world through other spaces. Ubwali aspires to make their landing a little softer than mine was.

The Hope Prize as a name was my best friend’s idea because she knows not just how much I adore my mother but how much of my writing is a result of everything she was and everything she did not get to be. When I started putting Ubwali together, I was in the middle of an editorial fellowship at Shenandoah and seized the opportunity to get mentorship to start my own magazine. My EIC at Shenandoah suggested a long-term partnership that would allow me to grow as an editor and support Zambian writers, and that is The Hope Prize’s birth story. For now, the focus is on Zambian authors, encouraging them to submit their best for a chance at the prize, which doesn’t just come with a monetary value but the opportunity to be featured in Shenandoah. I am so excited about what this will mean for the authors because Shenandoah is very supportive of its authors, and I believe it will be an excellent springboard for our author’s careers. Of utmost importance to me right now is raising funds to pay my authors, which I can only do through donations. I am optimistic that the prize is just the beginning, and I am working on a longer-term model that will see the magazine paying for all the art it publishes and the editors that make it possible.

IBRAHIM

How about your award-winning collection, Obligations to the Wounded? What inspired it, and how tasking was the process of completing it?

MUBANGA

Three people, honestly. First is my friend, Afua, who read a short story I wrote a few years ago and said it would make the perfect closing to my collection. At the time, I had just written maybe three short stories, so the idea kind of blew my mind. A few years later, in an interview with Alma at Cheeky Natives, Alma said something similar. We are friends now, Alma and I, and every few months, she would exert some peer pressure and ask for that collection. I worked on it for a few years, shifting things around, writing and rewriting pieces. It went through many titles, and, like The Mourning Bird, it faced a lot of rejection. Earlier versions even lost the Drue Heinz Prize two years in a row. My delete-rejections-on-sight policy serves me well because those rejections only exist in my mind; I have no proof to psych myself out. But the final push came from Foday Mannah, a writer friend whom I met through a prize we both lost years before. He read the entire collection a few months before the Drue Heinz deadline last year and was relentless in telling me to submit it. Finally, just to be like, “Ok, I did it”, I changed the title to Obligations to the Wounded (which I had been wanting to call it for a while) and clicked submit.

IBRAHIM

If you were to name three major things that are most essential to an emerging writer who wants to be successful, what would they be?

MUBANGA

Just two––reading and writing. The reading must be with the intention of learning from the work, and the writing will keep you going.

IBRAHIM

If you weren’t a writer, a lawyer, a PhD candidate, what other thing could you have been successful—or at least happy—at? Shock us with your answer here (laughs).

MUBANGA

I worked all through undergrad, so I have had every job under the sun. By the time I landed on lawyer, I knew for sure it was what I wanted to do. I don’t like boxes, so my career choices have been fluid, and my PhD is not in law or creative writing. Outside of work, I love decorating cakes. When my children were younger, and money was a lot tighter, I sold them out of my kitchen, but now that things have eased, I find that my best cakes are the ones I create for people I love. I am very passion-led in that way, but as a bakery business model, I don’t think that would work very well. If you ask my husband and children, though, they would say baker for sure, based solely on their birthday cakes every year.

IBRAHIM

What is something you would tell a young you who is just starting out as a writer?

MUBANGA

Young Mubanga was doing so much and being very hard on herself, even though she was doing her best. To her, I’d say the same thing I tell my students, which is: Trust yourself, that you are learning what you need to, at the pace you can, and in that same way, the fruits will show; after all, they say, drop by drop is the water pot filled.

IBRAHIM

Is there anything you’d like readers to look forward to—from you, Ubwali Literary Magazine, or elsewhere?

MUBANGA

Honestly, there is so much fantastic work from new writers. Our second issue has work from all over the continent and our third issue (due in October) will have exclusively Zambian work. I am always so excited to share their work in the magazine and their success afterwards. We will hold our first masterclass later in the year and have an incredible lineup of teachers across genres. Me, well, I’m always writing something, submitting something. My second novel has been done for a while, and my memoir in poetry is taking shape, so you’ll see me in the bookstores.

IBRAHIM

Thanks again for granting this interview. It’s been an amazing time talking to you.

MUBANGA

My pleasure.