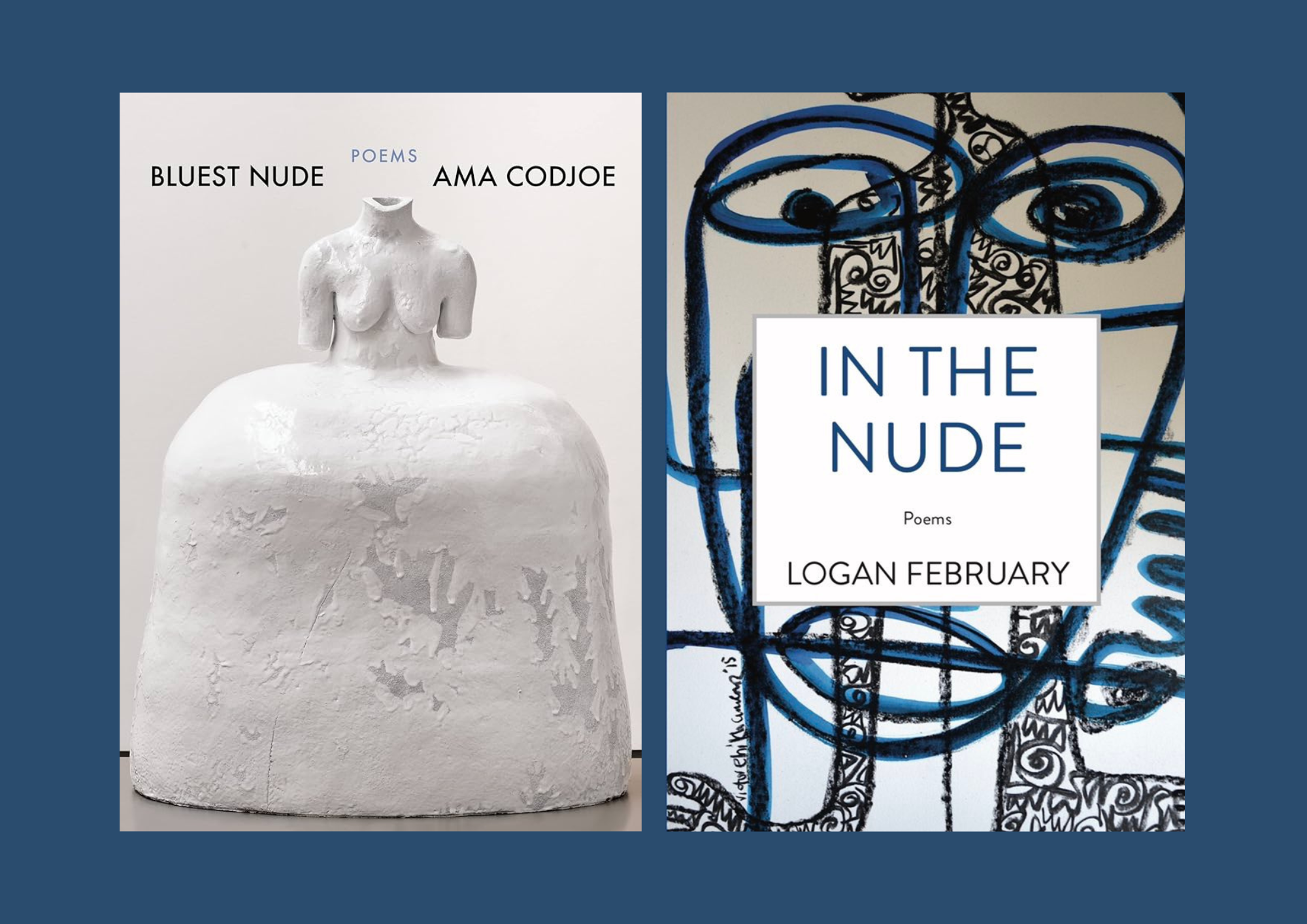

A Comparative Analysis of Ama Codjoe’s Bluest Nude & Logan February’s In the Nude

“Art is born and takes hold wherever there is a timeless and insatiable longing for the spiritual, for ideal: that longing which draws people to art.” ― Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago. This yearning for the ideal, for something beyond the material world, often finds expression through the body, a site of both limitation and substantial potential. In poetry, the body becomes a powerful vehicle for exploring identity, particularly for marginalized voices seeking to reclaim their narratives. Ama Codjoe’s Bluest Nude and Logan February’s In The Nude both explore this ground, using the naked body as a focal point for examining gender, queerness, and the convoluted relationship between self and society. Codjoe’s work reclaims the Black female body from historical objectification, while February’s poetry navigates the nuances of queer identity and desire. This analysis investigates how these poets use the naked body to express this “timeless and insatiable longing” for self-understanding and liberation.

The act of revelation of the naked body is seldom neutral; it is embedded in meanings that are social, cultural, and historical—often a site of power struggles and contestation. Ama Codjoe and Logan February are acutely aware of this fact and make use of nudity in their poetry not merely as a state of the physical body but as a metaphor for vulnerability, resistance, and self-centring. However, they approach this symbolism from the very different positions that a Black woman and a queer person would have. For Codjoe, nudity is linked with historical and contemporary objectification and commodification of the Black female body. Her poems grapple with this weighted history in an attempt to redefine agency and, thus, the storytelling of Black female nakedness. This may be in evidence in the title poem “Bluest Nude,” which says:

“In the flower of my body— / blossoms belonging, / at last, / to me, / sovereign / place, where I am no one / but myself.”

A declaration of her autonomy over herself is, conversely, one of resistance to those powers and structures which have dictated and sought control over it. The “flower” suggests a natural, inherent beauty independent of any external judgement. Later in the same poem, she writes:

“My bodies reveal nothing and conceal / nothing. Pin-up beauty, runaway, Venus / of the Circus Act, nightwalker, wet nurse, / odalisque, reclining nude. The women are me / and are not only me. Hers are the only eyes.”

Here, Codjoe is confronting straight-on some archetypes and stereotypes foisted upon women, particularly Black women, via art and popular culture. The gaze is hers now: “Ours are the only eyes,” relocating and rewriting this power dynamic back toward the experience and perspective of the women themselves.

Nudity to February, on the other hand, is intimately related to queerness and to the exploration of gender fluidity. In the Nude is a space for vulnerability, intimacy, and self-discovery, and a space to challenge conventional gender roles and expectations. In “Samsara,” the speaker declares, “I want to be naked. I want to wander.” The desire for nakedness here is not carnal but metaphorical for the yearning to be free from all chains that bind one to society and an ache for true self-expression. The image of “wandering” further emphasizes this sense of exploration and the search for identity. The theme of vulnerability is central to February’s exploration of nudity. In “Claw, Hoof, Paw, Hand,” the speaker offers themself to a lover in a state of complete vulnerability:

“Here are my wings. Pluck them clean… I’ve shed my skin, naked for the first time. Look at me, small burning reptile: a dragon who first ruins itself.”

An image of shed skin is invoked here to support the idea of transformation and rebirth, nudity being an essential stage in that. The readiness to be “ruined” underlines the deep level of vulnerability in being exposed, physically and emotionally. In “Hive,” February links nakedness to a refusal of shame and an embracing of queer intimacy:

“But here in the open, they are open. A woman’s body unfurls like spilled honey and everything else is washed away.”

This image of “spilled honey” is at once sensual and abundant, suggesting that nakedness, in queer love, is a source of joy and liberation. The phrase “everything else is washed away” denotes how, within the space of intimacy, judgment and expectations of society are bereft of power.

One of the strong similarities between the two books of poems is the way they both explore the complexities of gender and the body, though their engagement with queerness differs in terms of its directness and focus. While not always naming identities explicitly as “queer,” Codjoe’s work queers the body through disrupting heteronormative expectations and centring Black female experiences. February’s poetry directly engages in queer identities, specifically non-binary, fluid, and unconventional gender expressions that disrupt heteronormativity through the lens of queer desire and experience. Codjoe works within a space of what might be termed “implicit queerness.” Even when her poems do not explicitly name queer identities, they challenge the assumed heteronormativity of the female body and experience. By centring Black women’s experiences and exploring themes of female intimacy, desire, and self-possession, Codjoe disrupts traditional heterosexual narratives.

In “Two Girls Bathing,” the intimate scene between speaker and cousin Carol, while nestled within a familial context, feels pervasively suggestive of nascent female intimacy and exploration. The ease of Carol in her nakedness and the speaker’s growing self-consciousness creates a space where the boundaries of traditional female relationships blur. “This was before / boys became unlike girls” suggests a pre-heteronormative space, a time of fluidity and shared experience before societal divisions were cemented. This state before division may be understood as queerness, the refusal of imposed gender roles and expectations. As discussed, the poet’s reclaiming of the Black female body in itself is an act of queering. Not being bound to societal ideals of beauty and femininity in conjunction with race, Codjoe queers the very notion of womanhood. It’s interesting because, through such an affirmative position-in “Bluest Nude,” for instance, the speaker takes back her right of self-governance over the body; “sovereign / place, where I am no one / but myself,” an announcement of self-belonging. That becomes quite an active way to repudiate exterior positions or expectations of some sort. It is with this self-possession, this reclaiming of the body for and by oneself, that this work escapes the strictures of heteronormative structuring and takes up, if you will, its queerness of definition.

February’s poetry speaks directly to, and of, queer identities and experiences-especially those challenging mainstream conceptions of gender. In The Nude comes an exploration aplenty of what it means not to be bound by conventional binaries of gender-non-binary, fluid, unconventional. Desire and intimacy figure frequently in these poems, often fore-grounding queer articulations of love and relationship in a counter-narrative against heteronormative representation. In the poem, “Hive,” the speaker describes two girls who “know wetness like history & hiding like a second skin.” This image of “hiding” speaks to the historical and ongoing need for queer individuals to conceal their identities in a heteronormative society. Yet the poem also celebrates the intimacy and connection these girls find in their shared experience. This is the contrast which tangles between concealment and exposure, the pull of societal pressure with the want for real self-expression. Sweet and fluidity in “spilled honey”—sensual and full of meaning—queer love is a source of joy and liberation. In this part, the poet has also pointed out the issue of gender identity and expression. The poem “Stillbirth, Yemoja” ends on a note in which the speaker declares a desire to transcend typical gender roles:

“The kind of man who wants to be the kind of woman who bears children / that sound like birds when they cry.”

The crossing of gender lines reflects a negation of certain fixed identities and a desire toward more fluid and expanded conceptions of gender. The central desire to hold both masculine and feminine qualities in themselves is a pervasive theme in February’s work, problematizing the very idea of any stable, fixed gender identity. In poems like “The Slut’s Prayer” and “Fuckboys,” February explores queer desire and sexuality with a raw and unflinching honesty. These poems work to contest societal shame and judgment around queer bodies and relationships and attest to the value and beauty of queer experiences.

To speak to societal expectations of the naked body, society casts a multifarious lattice of expectations on the naked body with regard to acceptability, desirability, and permissiveness. Most of these expectations are grounded in power dynamics, historical contexts, religion, and cultural norms, which influence individual relationships with their bodies. Both Ama Codjoe and Logan February’s poems deal explicitly with these societal pressures and how the naked body becomes a sight of both conformity and resistance.

According to Susan Sontag, in On Photography, “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves.” This idea of the external gaze shaping our understanding of the self is crucial to understanding the politics of nudity. Codjoe directly confronts the objectification of the Black female body in her work, especially the pressure to live up to idealized and often unattainable standards of beauty. This is further compounded by the historical context of slavery and its lasting legacy, which has hypersexualized and dehumanized Black women. In “Poem After Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima,” Codjoe writes to another kind of liberation—one that outstrips the violent imagery of Saar’s work into a radical self-possession. The speaker says, “Gonna try on my nakedness like a silk kimono.” This image speaks to a gentle, self-embracing nudity, not defined by external judgment or exploitation. It is a taking back of the body for the self, refusing the objectifying gaze. The poet extends it to show how societal expectations can distort one’s view of one’s own body. The fragmented structure of the poem and the recurring refrain of “another incident…” point toward the continued violence done to Black bodies, most specifically at the hands of law enforcement. This is the violence that starkly reminds one of the vulnerabilities of the Black body within a system of racialized power. The speaker’s wish to be “seen clearly or not at all” exclaiming to the frustration of being constantly misperceived and objectified. It is a demand for recognition of her full humanity beyond the limiting stereotypes imposed upon her. The final image of the speaker drawing herself “as water from a well” points toward not an act but a process in self-creation and self-definition, where the speaker is constantly resisting powers at work outside her which seek to define her.

February’s poetry dismantles social constructs concerning the body, advocating for multiplicity of experience and expression. In “Gluttony,” the speaker contrasts her own experience of nurturing and giving with the longing to be “like the others—not breathless in my mother’s embrace.” This desire for another kind of relationship—a relationship not predetermined by traditional familial and gender roles-speaks volumes on the conundrum posed by meeting societal expectations within a queer context. The speaker’s inability to tell their mother about kissing a boy accentuates the societal pressure to conform to heteronormative expectations and the pain of being unable to fully express one’s true self. Judith Butler’s concept of “performativity” is relevant here. Butler argues that gender is not an inherent quality but rather a performance, a series of repeated acts and gestures that create the illusion of a stable identity. February’s poems press on the performative nature of gender, testing the idea of a “natural” or “essential” way to do masculinity or femininity. Poetic for February, fluidity challenges fixed categories and disrupts the very ground on which expectations of the body are laid down.

Another important aspect to note in this comparative analysis is at the juncture of race and gender. Neither the experience of race nor that of gender is independent per se; both intersect and go to inform one another in quite composite and often far-reaching ways. This renders it quite significant to engage the question of the body’s representation, particularly because societal expectations and stereotyping are many times attached to the coming together of racial and gendered biases.

Codjoe’s exploration of the naked body is inextricable from her experience as a Black woman. Her work confronts the particular ways in which Black female bodies have been and continue to be objectified, hypersexualized, and made to bear violence. This historical context, born from the legacies of slavery and its relentless heritage, adds an extra layer of complexity to her exploration of nudity. The fragmentation in the poem, “Bluest Nude,” for instance, in the nature of the poem’s flow and refusing further description of the “incident,” itself reifies such acts into unspeakability and trauma. Codjoe’s “Poem After Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” is one of those poems that directly engulfs into itself the historical representation of Black women in popular culture. Thus, in reimaging Aunt Jemima, a figure attached to servitude and mammy stereotypes, she reappropriates agency within that harmful representation. These lines allude to a reclaiming of the body as a site of power and self-expression:

“Gonna try on my nakedness like a silk kimono” and “Gonna smear the sun like war paint across my chest.”

This is also a reclamation not of negative stereotypes but one that creates new narratives by centring Black female experiences and their desires. The idea of “double consciousness,” coined by W.E.B. Du Bois, is very applicable to Codjoe’s work. He explains that the double consciousness feels “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” In this poem, Codjoe wrestles with this double consciousness, wrestling herself in internal self-perception set against the judging face of society. She centres the Black female gaze in such a manner that the dominant white gaze is contested, and Black women’s experiences are legitimized.

Though at the core, February’s work deals with queer identity and gender fluidity, their work does intersect with the theme of race and gender, particularly body politics. While the speaker’s racial identity is not explicitly stated within these poems, the work still exists within a racialized context, particularly in the way it engages with vulnerability and the threat of violence. In “The Slut’s Prayer,” the speaker’s defiant assertion, “I do whatever I want because I could die any minute,” takes on additional weight when considered within the context of racialized violence against queer bodies. The line, therefore, “I don’t mean YOLO I mean they are hunting me,” links the speaker’s particular vulnerability with the general persecution and danger of the surrounding society. Further, the reference to “butcher’s wax-paper” in the poem is complemented by the note sent to the family:

“We regret to inform you we found him in the arms of a boy. / We had to do what we had to do,” evoke the very real threat of violence faced by queer individuals, but especially queer people of colour. It is in this sense that the connection to violence is crucial for any understanding of the intersectional nature of February’s work, showing how race and queerness compound experiences of vulnerability and marginalization. Although race is less central to the work of February than to Codjoe’s, where it appears is significant. And it indicates one clear thing: at all times, experiences of gender and sexuality are modulated by wider contextual features such as race. Indeed, both poets have managed to show, each in their different way, how impossible it would be to research the body and its representations if the intersections between race and gender were not accounted for.

In Bluest Nude and In The Nude, Ama Codjoe and Logan February move beyond the traditional confines of contemporary poetry, bringing forth an in-depth look at identity, gender, and queerness through the prism of the naked body. Their works meet at that crossroads, excavating and interrogating race, gender, and queerness but diverge in the textures of their approaches; Codjoe grounding her work in interlaced mythic heritage and collective memory, whilst February’s verse feels like a burning confessional diary. Put together, these collections demonstrate the verve of contemporary poetry as a space to push convention and redefine identity, offering the reader not just a mirror but also a window to an unapologetically free selfhood. It is this fearless reimagination of the naked body that seals their work as important additions to poetry today.

Ibraheem Uthman

Ibraheem Uthman is a Nigerian poet, essayist, and literary mentor. He is the author of Mind of a Bard, Managing Editor of The Nigeria Review, and curator of the HIASFEST Literary Panel. A two-time winner of the National Library Prize and HCAF Excellence in Creative Writing Award 2025, he was also a BillWard Prize runner-up for Emerging Writers (Essay).