Elaine Showalter describes feminist critique as an “ideological, righteous, angry, and admonitory search for the sins and errors of the past,” while she sees gynocriticism embracing “the grace of imagination in a disinterested search for the essential difference of women’s writing.” Reading Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow through this lens illuminates the experiences of young Nigerian women and the societal pressures surrounding their bodies.

Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood famously presents Nnu Ego’s poignant question: “God, when will you create a woman who will be fulfilled in herself, a full human being, not anybody’s appendage?” This inquiry encapsulates the preoccupation of Nigerian women writers since Flora Nwapa—the first woman to publish a novel in English in Nigeria. These authors, from Emecheta to Adichie, from Mariama Bâ to Chika Unigwe, are not just observers of the many social paradigm that affect women. They are also keen about changing the systemic and institutional system that have become oppressive for women across generations. Their writings, whether predetermined or spontaneous, have countered hegemonic and stubborn oppressive patriarchal ideals and traditions. Their writings align with Showalter’s first category of feminist critique: woman as reader. In her book Towards a Feminist Poetics, Showalter explains that this category encompasses how female writers confront the stereotypes and patriarchal ideologies that have historically shaped literary portrayals of women. Thus, most of Nigerian women writers have used literature as a platform to highlight the stereotypical perception of womanhood and refuting traditional ideological assumptions about women. However, in contemporary postmodern experience, this approach, which often centers on the traumatic legacies of women’s suffering, although necessary, may inadvertently reinforce the very oppression they aim to dismantle by continuously framing women’s experiences within the context of historical victimization.

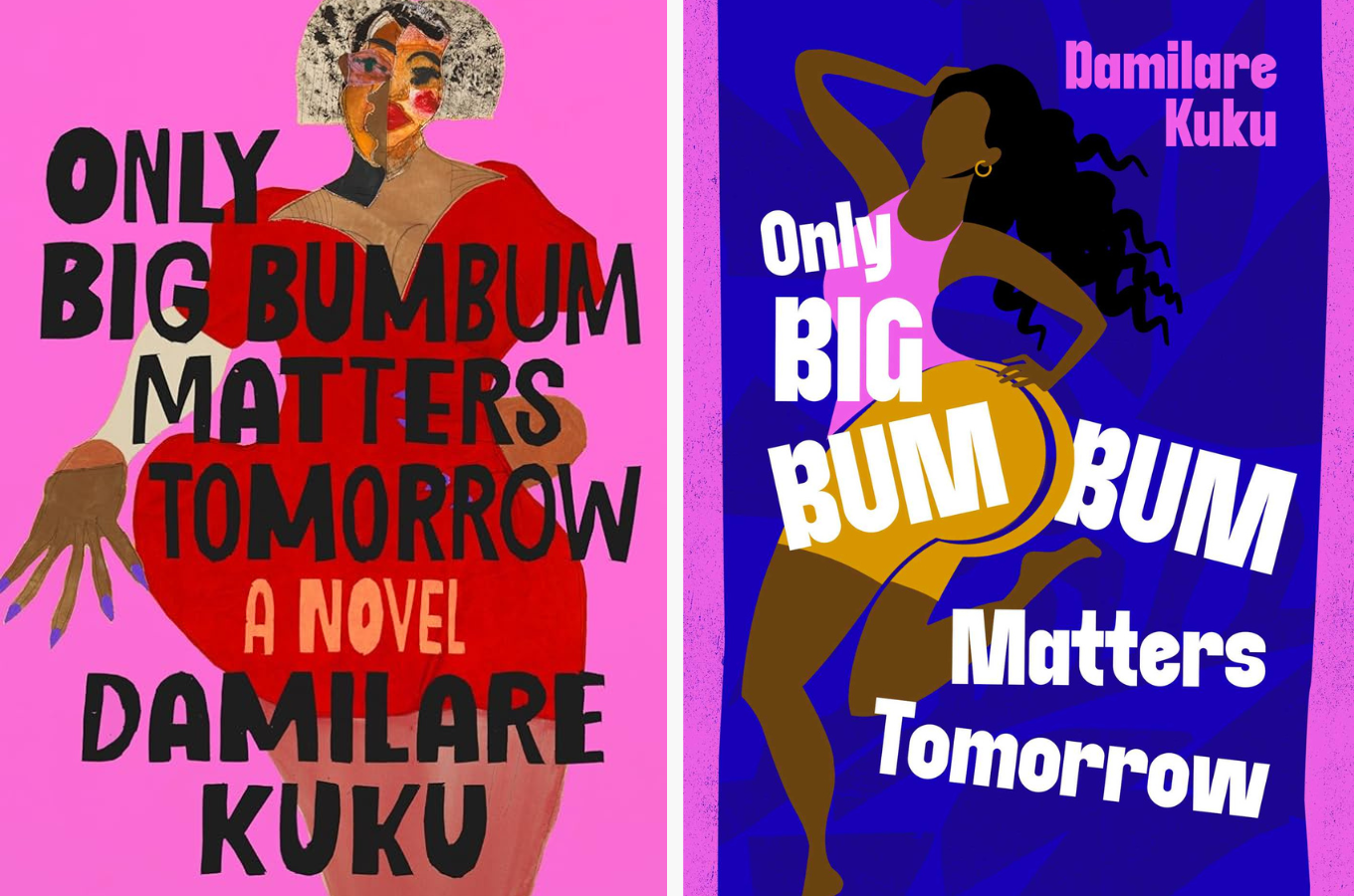

Damilare Kuku, in her debut, Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow breaks from this tradition. Rather than recounting women’s historical struggles, Kuku navigates the terrain of modern female identity through the lens of body politics in the digital age. Her novel shifts the focus from systemic gender oppression to the contemporary woman’s relationship with her body, exploring themes of body-image obsession, self-perception, and societal pressures in a way that is unapologetic and refreshingly direct. Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow breaks new ground by acknowledging that the experience of being a woman today is shaped not only by historical oppressions but by the contemporary societal obsession with the body, beauty, and visibility. The novelist redefines what it means to write women’s stories in a digital age as her work refuses to confine female characters to the well-worn tropes of victimhood or noble suffering. Her novel is a commentary on the ways women today navigate the intersections of autonomy, sexuality, and societal validation. Kuku gives voice to a generation of women navigating these postmodern realities, offering a nuanced perspective on how they might reclaim their identities in a world that often commodifies and objectifies them.

Writing the Woman and Her Body

Kuku’s bestselling debut novel is a gendered, feminist narrative that explore the deeper, often unspoken pressures on Nigerian women, exploring both their internalized struggles and the external forces conditioning their sense of self. The narrative charts the obsession of a young woman about her look and appearance while exploring the shifting social and transcultural forces that shape women’s perceptions of their bodies.

Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow begins with a striking declaration by the protagonist, Temi, at her father’s burial: her intention to “renovate her backside” through liposuction. This declaration elicits varied awkward reactions from family members, who were taken aback by the timing but also surprised that it came from her. It was a moment when their grief was still raw, and they were collectively processing the loss of the family’s father figure while anxiously awaiting the lawyer to read his will. From there, the narrative progresses into the the varied reactions of those present—her mother, Hassanna; her sister, Ladun; and her aunts, Jummai and Big Mummy. Through flashbacks and personal reflections, the story shifts between the experiences of these characters, exploring their psychological processing of Temi’s dilemma.

From Temi’s narration, we witness her lifetime of grappling with how her appearance communicates value or inadequacy, shaping her actions and insecurities in a world where her body has become a subject of public perception. You start to read the novel, and there is a certain conditional awareness about how she perceived her body from the very beginning. She begins her narration with a simple yet profound statement, “Your bumbum has always been flat.” This self-assessment is not just personal; it evolves into a broader narrative that critically explores and renegotiates gendered identity. The criticality of this very issue that Kuku tackles find utmost complexity in the narration: the need – rather than choice – to adopt the second-person “you” and its possessive form, “yours” to narrate the protagonist’s story. This narrative device is not simply a stylistic choice—it is a means to reflect the societal conditioning of women, where the self is constantly assessed, measured, and judged by external standards.

One of the influences to be drawn from the characters in Kuku’s debut novel is similar to the troubles that female characters in Toni Morrison’s work suffer, particularly the pressures surrounding beauty and identity. Temi is a similar character like Peculiar in Morrison’s The Bluest Eyes, who was alarmingly responding to the demands about beauty standards in a racialised American society. This left her conflicting and she longed to fit in to the demands about identity and beauty in her time. In portraying the contemporary Gen-Z woman, Kuku captures the complexities of navigating a postmodern world where media and social platforms relentlessly promote specific beauty ideals. These standards, though pervasive, are deeply internalized, shaping how young women perceive themselves and their bodies. Kuku is acutely aware of how these influences create an ongoing struggle for identity and self-acceptance, as young women seek ways to meet, challenge, or escape these demands.

The exploration of the female body is a similar trope in Tsitsi Dangarembga’s This Mournable Body which explored the postcolonial, patriarchal conditioning that oppresses women, particularly highlighting the struggles of the educated woman who remains trapped within these structures. In her portrayal, Dangarembga illustrates that the female body is a site of burden, worn down by the oppressive forces that the woman, in her attempt to navigate them, barely notices. The narrative frames the woman’s body as a reflection of the existential condition of postcolonial subalternity, ostensibly connected to gender politics, religion, and the socio-economic environment, all of which collectively shape the politics of difference, transforming her body into a locus of suffering and resistance. Racism, xenophobia, and capitalism are depicted as forces that imprison the female body in postcolonial Zimbabwe, revealing the complex layers of oppression women face. In contrast, Kuku adopts a more convivial approach in her exploration of the burdens faced by the young contemporary African woman. Her writing reflects the aspirations of young Nigerian women, particularly in relation to body image and self-perception in a rapidly evolving society.

While Dangarembga’s focus is on the older generation of women who endure systemic oppression and weariness, Kuku turns her gaze toward the struggles of younger women. She highlights how contemporary women contend with the pressures of a digitally mediated world, where beauty standards and body image are shaped by social media and popular culture. Kuku’s narrative suggests that while older women faced the crushing weight of postcolonial and patriarchal forces, the younger generation are wrestling with new challenges—ones tied to the desire to conform to beauty ideals imposed by a hyper-connected, image-driven society.

A Gynocritical Discursive Framework

American literary critic, teacher, and founder of gynocriticism (a school of feminist criticism that focuses on “woman as writer”) Elaine Showalter acknowledges the challenges of defining women’s writing but views gynocriticism as a means to understand women’s relationship to literary culture. Showalter posits that feminist critique often involves an “ideological, righteous, angry, and admonitory search for the sins and errors of the past,” while gynocriticism, on the other hand, embraces “the grace of imagination in a disinterested search for the essential difference of women’s writing.” Through gynocriticism, Showalter provides critics with four models to examine the nature of women’s writing: the biological, linguistic, psychoanalytic, and cultural models. The application of these frameworks to Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow, illuminates the portrayal of the contemporary young Nigerian woman and the biases she navigates.

Showalter’s biological model of gynocriticism examines how a woman’s bodily experiences—particularly those related to reproduction, motherhood, and sexuality—shape female writing. In Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow, set in a post-COVID reality, the protagonist’s body is a battleground for cultural and societal expectations. From a young age, Temi has internalized these pressures regarding her body shape. In primary school, she was nicknamed “blackboard,” and in secondary school, she was referred to as a “mopstick.” By the time she reached university, she was mocked for her “flat yansh.” She endured these labels with bitterness, compounded by the abuse from both peers and adults. A particularly humiliating incident occurred when a bike man slapped her buttocks, mocking her for having a flat backside. In response, Temi began padding her Bumbum, stuffing singlets into her pants to give the appearance of a fuller shape. Throughout her life, she has suffered indignities and emotional abuse due to her body, which has instilled in her a deep sense of shame and inadequacy. This has led her to believe that her body will never be enough. Eventually, she resolves to undergo liposuction to reshape her backside.

Unlike Temi, her curvy sister Ladun, who has a striking body shape, faces the very predicament Temi always longed for—being the center of male attention. Ladun constantly struggles to fend off men who are primarily interested in her physical appearance. Although she doesn’t endure the same disdain her sister suffers, she is constantly objectified and desired by men because of her body. These contrasting experiences between the sisters reflect Showalter’s biological model of gynocriticism, which emphasizes how gender differences are projected in women’s writing. This model asserts that texts by women should center on the distinctiveness of female experiences. Kuku explores these varied experiences, shaped by biological differences, and weaves them into her profound themes and critical issues.

The cultural model of gynocriticism goes beyond merely identifying gender differences in women’s writing; it delves into how social, historical, and cultural contexts shape the way women write and experience the world. In this framework, Kuku’s writing is a critical reflection on the complexities of postmodern Nigeria, where exchanges like body shaming, body-image obsession, and the growing trend of body enlargement are not stemming from personal insecurities but broader social tensions. These tensions reflect a societal shift, where women’s bodies become sites of cultural conflict and negotiation, deeply influenced by patriarchal expectations, media portrayals, and economic disparities. Kuku explores how these pressures create anxieties about physical appearance, particularly among younger women, and how body-image obsession becomes intertwined with self-worth, identity, and social acceptance. This aligns with Showalter’s observation that women’s experiences are not isolated from their social environments but are shaped by broader discourses on beauty, gender roles, and power dynamics.

The phenomenon of body enlargement, for example, is reflected as a coping mechanism for navigating societal pressures since it offers a form of escape or empowerment in a culture that commodifies women’s bodies. In this context, Kuku is not merely reflecting on individual experiences of body image but critiquing the broader sociocultural framework that defines and constrains female identity. Her narrative is a critical narration of how Nigerian women, post-COVID, are navigating new forms of societal pressures, while still grappling with longstanding cultural norms. This aligns with Showalter’s cultural model of gynocriticism which emphasizes that women’s writing must be understood within these overlapping systems of influence—social, historical, economic, and political—all of which shape the female consciousness and expression that Kuku so poignantly captures in her work.

The psychoanalytical model explores the emotional and psychological dimensions of female characters, examining how these are shaped by their societal and familial contexts. In her narrative, Kuku explores the psychological experiences of women across generations, particularly in relation to the female body. After Temi’s decision to undergo the cosmetic procedure, the reactions of the four women present at the time reveal the deep-seated psychological and emotional reflections each character holds about their own bodies. Jummai and Hassana—Temi’s aunt and mother, respectively—reflect on their personal experiences and how their bodies have influenced their interactions with men and society. The narrative reflects the social conditions that shaped woman’s self-perception and the personal experiences that shaping their psychological development. Thus, we see that a woman’s identity is profoundly influenced by her experiences, relationships, and the societal demands placed upon her.

The linguistic model emphasizes how women use language to express their experiences and challenge patriarchal norms. In Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow, Kuku captures the complexity of women’s identities and experiences in modern Nigeria employing contemporary linguistic techniques. Her writing is fluid and engaging, reflecting the realities of contemporary life for Nigerian women. Kuku critically examines the influence of advertisements and media in shaping societal perceptions of female identity. She underscores how these platforms often perpetuate stereotypical images, promoting narrow definitions of beauty, femininity, and success, and revealing the internalized pressures that women face as they navigate these constructed ideals.

Yinka Adetu

Yinka Adetu holds an M.A. in Literature and is a culture writer and literary critic. His works have been featured in The Republic, Afrocritik, The Lagos Review, and The Nigeria Review. He also contributes as a freelance book reviewer for the Journal of African Youth Literature.