Novel synopsis

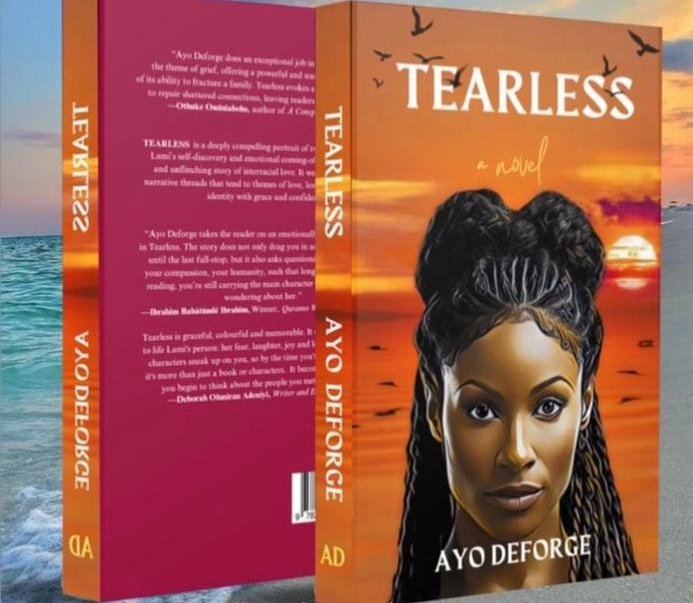

Tearless follows the life of Olamide’ Lami’ Davis, a twenty-four-year-old French teacher based in Lagos. Utilizing a distinct temporal leitmotif, Deforge shunts us between Lami’s painful past and her pallor but promising present. Having grown up in a home rife with tension and varying degrees of abuse, Lami approaches life and love with painful hesitation. However, her desire to reunite her siblings and fulfill the promise she made to her dead mother remains as strong as oak. Juggling this burdensome task and the stress of quotidian life as a French tutor in Lagos, Lami goes through a painful journey of self-discovery. Like any journey worth its salt, Lami finds the most unexpected gifts on the way: friendship in the person of the ever-effervescent Ada and an unlikely romance with a certain Frenchman. With themes of loss, grief, fatherlessness, francophilia, and redeeming love, Deforge weaves a beautiful narrative tapestry that is timely, enchanting, and entertaining.

But ‘time heals all wounds’ is a disingenuous lie. It is how we, as a society, obfuscate the fact that some wounds do not heal. They grow, they evolve; you adapt. Becoming part of the fabric of your life, they embed like a mole.

Time is Not Your Healer by Muti’ah Badruddeen

I’ve often wondered the worst age for one to lose a parent. Is it more painful when you are a baby, with no knowledge of them and zero memories to agonize over? Or when they are old and wrinkled with all the many memories of them haunting your every waking moment? Or maybe it is somewhere in between, when the memories are fewer, and your heart bleeds over all the time you’ll never get to spend with them. The truth is death always feels like robbery, regardless of whether it strikes in the morning or evening of life. As in Lami’s mother’s case, death is especially painful when it snatches someone before they have a chance to experience a peaceful life.

When talking about loss, we rarely talk about how grief is a comforting blanket tethering us to the defunct soul. Although we know we should move on, moving on feels like betrayal, an admission that we can be happy without them. When the memory of their laughter starts to fade, and the pixels of their face become blurry in our mind’s eye, we panic. Why? Because after months have become years, this painful feeling in our center is the only tangible reminder that they were once here and we loved them immensely. The only reminder of the injustice of their death. For Lami, there was grief, a pervasive phobia, and a desperate need to reunite her siblings—and she ambled through life juggling all three.

We also rarely think about how death in itself feels like a betrayal. The promises of future birthdays that will now be spent alone. The memories you should have made together. In Lami’s case, her mother was a lighthouse guiding her out of the dark, buoying her to safety when her fears threatened to engulf her:

‘Who are you afraid of?’ Mama would ask. ‘Who is coming to get you while I am here? Am I not your eyes when yours are closed? At other times, she would say, ‘No monsters will come and get you while I am here. Don’t you trust me enough to protect you?’

As the older Lami battled with her fears, I often saw the little Lami waiting for her mother to be her eyes, to protect her from the monsters lurking in the shadows. How do you learn to trust again when the person you trusted the most leaves you alone to face the world and all its darkness?

You must cry. You must shed tears,’ Papa continued to shout as he struck harder and faster. ‘…By the time I am finished with you, the evil bird in you will fly away and never return.’

Tearless, by Ayo Deforge.

Do not defend.

Do not engage.

Do not explain.

Do not personalize.

This is the mantra for dealing with problematic/toxic personalities. It is often said that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction—and difficult characters like Lami’s father are always looking for that reaction. Mr. Davies was a source of terror for his wife and children. Any little ray of happiness they created vanished when he stepped into the room. Like Mrs. Davies, many women stay with abusive women just to give the children the illusion of a two-parent household, to ensure that their future marriage prospects are not doomed by a mother who couldn’t bear her marital cross with saintly humility. They fail to realize that sometimes, you leave for the sake of the children. To show them that love is not pain and that it is okay to start afresh when things don’t work out.

While Mr. Davies disliked all his children, his hatred for Lami was unique. Although he said her eponymous flaw was the reason for this hate, it had more to do with her resemblance to him, a resemblance that was only skin-deep. Looking at her probably brought forth unaddressed insecurities. So everything he did to her was done to get a negative reaction, to make her say or do something that would calm his insecurities and justify his hate.

C’est cela l’amour, tout donner, tout sacrifier sans espoir de retour.

Albert Camus

One of the many high points of the book was watching Lami and Nico’s love blossom. With their serendipitous meeting, I half-expected the duo to chart a whirlwind romance. I was pleasantly surprised to see Deforge had other plans. Their love was unhurried and deliberate, like a home-cooked meal. It was evident Nico had deep feelings for Lami. However, he gave her space and allowed her to fall for him at her own unique pace and on her own terms.

In today’s world, love is often a placeholder word for ‘physical attraction’ or ‘lukewarm affection.’ Relationships, on the other hand, have become an unspoken competition of take and take. A meeting ground of flawed human beings trying to love each other through trauma-blurred lenses. With the romance between these two characters, we once again relearn what love truly is. Love is patient. It is kind and understanding. It doesn’t insist on its own way. Instead, it prioritizes the other person. And it becomes even more beautiful when the other party does the same.

Part of Lami’s evolution was learning to love without inhibitions, allowing herself to take a chance on love despite being terrified of getting hurt. From the instant we stepped into the past, it was evident that Lami loved her father and wanted his approval. Even when he rejected and punished her for her eponymous flaw, that desire for acceptance flickered on like a stubborn candle in the middle of a storm. Mr. Davies, however, succeeded in extinguishing that love when he gave Tutu away after his wife died.

It was as though a part of my soul tore itself away from me, and flew after the car, Lami narrates. At this point, we sense a shift. Any illusions she must’ve had about her father crumbled, and her focus turned to reuniting her siblings. After being betrayed by the first male figure in her life, relearning to trust and love a man was an uphill task for Lami. Her knee-jerk reaction with men was flight. Nico’s love came with a friendship that Lami’s hurt inner child needed. A safe place where she could let go, be herself, and wholly depend on someone else without being chastised, mocked, or rejected.

The best novels are those that are important without being like medicine; they have something to say, are expansive and intelligent, but never forget to be entertaining and to have character and emotion at their center.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

For me, there are two types of books: pageturners, with so beautiful a narrative, and themes that are twice as entertaining. These books are unputdownable and demand to be read in one sitting. The second group is a more intense read. Like cigarette smoke, its lessons sit heavily on your person and follow you throughout the day. You must take your time with this type of book because its subject matter demands to be reflected on. Tearless manages to be both all at once. Deforge handles heavy themes with so much grace and gumption but skillfully lightens their density with memorable dialogue, a toe-curling love story, and depictions of France that leave the reader longing for the sun-dappled[1] streets of Paris.[2]

MaryAnn Ifeanacho

MaryAnn Ifeanacho is a graduate of Creative Writing from the University of Hertfordshire. Her works have been published in the African Writer’s Magazine, JAY Lit, and the Kalahari Review. MaryAnn was shortlisted for the 2011 UBA Essay Competition, the 2017 African Rubiz Prize for Prose, the 2017 Poets in Nigeria (PIN) Food Poetry Competition, the 2023 Fab Prize for Children’s Fiction, and the 2024 WTAW Alcove Chapbook Competition. Her short story “Mykonos in Congealed Blood” was published as part of Flame Tree Publishing’s African Ghost Stories Anthology in April 2024.