Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Africa’s pen warrior, died on May 28, 2025, at the age of 87. He passed away in Buford, Georgia but his life’s work lives on across the continent and far beyond.

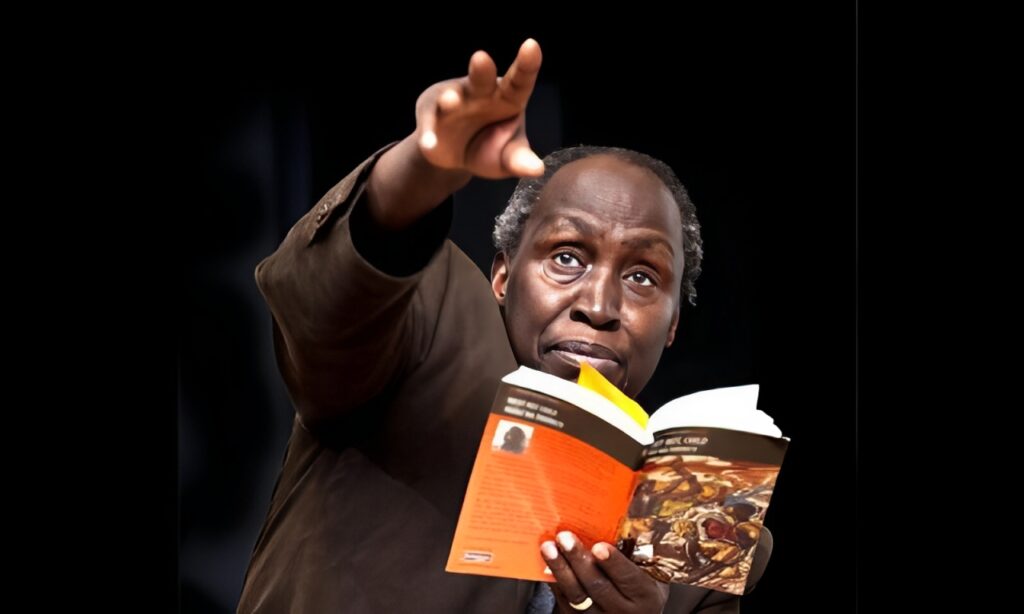

A writer, thinker, teacher, and revolutionary, Ngũgĩ spent more than six decades battling to restore dignity to African language, literature, and identity. His pen was his weapon, and with it, he inspired a movement.

Born James Ngugi in colonial Kenya in 1938, Ngũgĩ saw the brutal impact of British rule. His homeland was bleeding, not only from violence but from silence—silence forced by a foreign language, foreign religion, foreign rule. He made it his life’s mission to fight that silence.

In the 1960s, Ngũgĩ emerged as a powerful new voice. His first novels, Weep Not, Child, The River Between, and A Grain of Wheat, written in English, quickly became classics. These were not just novels, they were testimonies. They told stories of land, love, betrayal, and liberation. He wrote about Kenya’s fight for independence, and how colonization left deep wounds even after the British left.

But Ngũgĩ was never content with just telling stories. He wanted to change the story. In the 1970s, he took a radical turn: he stopped writing in English. He began writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue. For him, language was not neutral, it was political. English, he argued, was a tool of control. If African people could reclaim their languages, they could reclaim their minds.

This choice came with a price. In 1977, after co-writing the Gikuyu play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), which exposed corruption and inequality, the Kenyan government arrested him. He was held without trial in a maximum-security prison. But prison could not break him. There, using toilet paper and a smuggled pen, he wrote Devil on the Cross—a bold satire on greed and neocolonialism.

Exile followed. Ngũgĩ lived in Britain and later in the United States. Yet exile never meant silence. He continued to speak out, teach, and write. Decolonising the Mind, published in 1986, was more than a book, it was a declaration. In it, Ngũgĩ urged African writers and scholars to abandon colonial languages and to revive African tongues. It remains one of the most important texts in African and postcolonial literature.

From lecture halls at Yale and UC Irvine to literary festivals in Accra, Nairobi, and beyond, Ngũgĩ’s presence was electric. He was not a writer who sat safely behind a desk—he was out in the world, challenging the powerful and encouraging the young. His novel Wizard of the Crow, published in 2006, was a sprawling, funny, fearless critique of dictatorship and greed. It proved that his fire had not dimmed.

His work is studied in classrooms, quoted in protests, and remembered in song. He taught that to speak one’s own language is to claim one’s full humanity. In death, as in life, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o reminds us that the battle for the soul of Africa is not yet over—but the words to fight it have already been written.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o did not just tell stories. He restored voice. He restored pride. He reminded us that to write in your own tongue is an act of courage—and an act of love.

Rest in power, Ngũgĩ. Your voice echoes still.