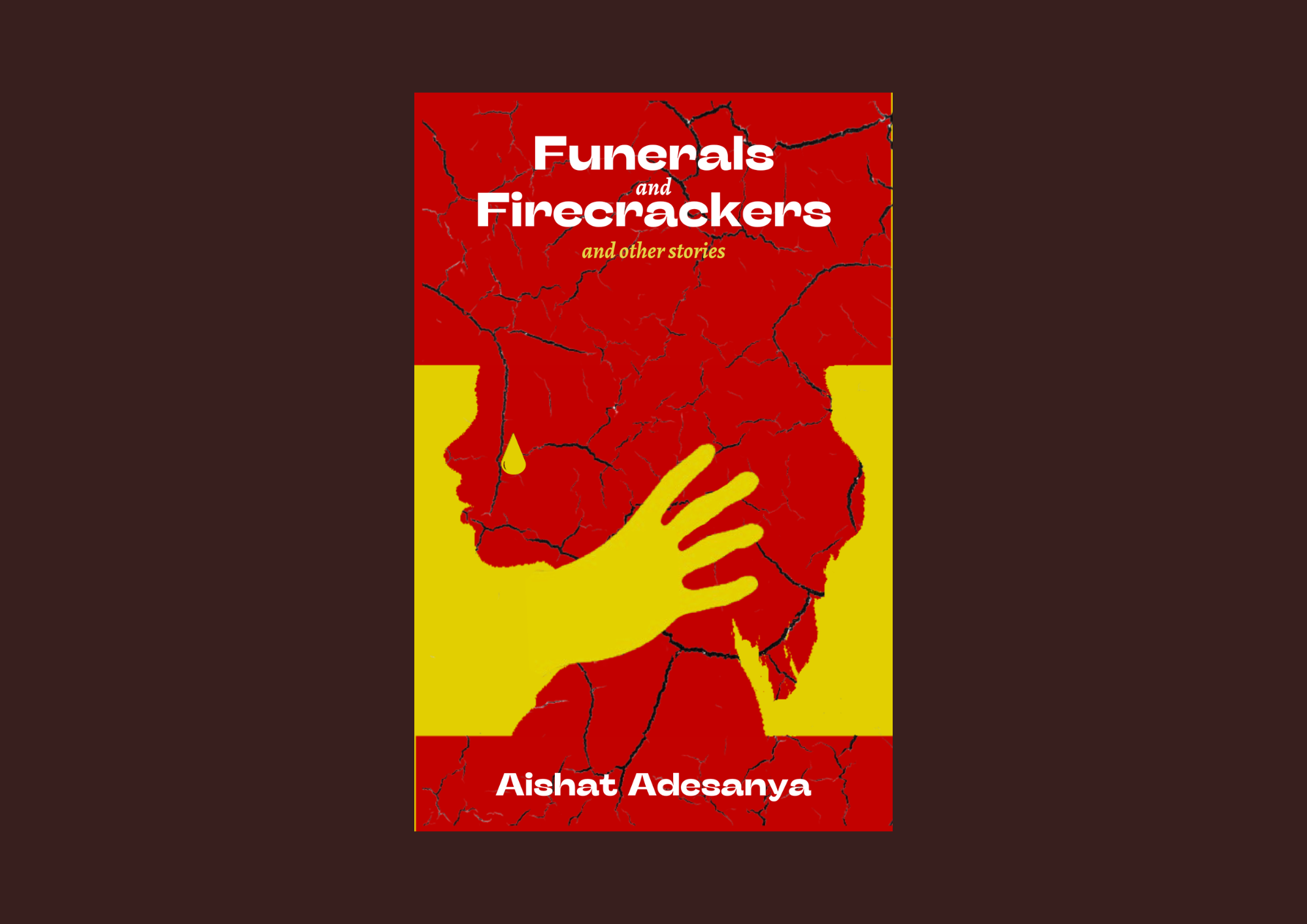

The key to an overall memorable collection of short stories rests in a complex balancing act. It is about the art of successfully balancing the individual narratives, themes, pacing and world-building in each story while ensuring that each story contributes to the collection’s overarching theme. It is an exercise of ensuring that even the stories’ order contributes to the overall collection’s pacing and development. Aishat Adesanya’s Funerals and Firecrackers is a masterclass on executing these technical aspects.

The collection explores numerous themes, including coming-of-age, ambition, and spirituality – all of which are undergirded by the overarching themes of grief and trauma. The order of the stories starts with the relatively lighter and somewhat comedic tale of “Dumebi”, who having lost both her parents, finds mentorship in the most unlikely of places. “Dumebi” is followed by “Funerals and Firecrackers”, “Moths and Fireflies”, “The Typewriter”, and then “Elation”. These stories share a similar rhythm. They are either set in Nigeria or find their roots there. There is a certain cadence with which Adesanya writes these stories. It invites both calm and intrigue. This style allows for the thematic and narrative intensity to gradually increase as one moves down the line of stories. “The Oddity”, which is aptly titled, is in the middle and acts as a bridge leading to the second half – the strange, graphic and at times, unreadable stories that are “RÁntí Omo Eni Tí ìwo ń Se”, “Fragile Façade”, “Jemimah”, and “Fugue”. “The Oddity” is just as graphic and macabre a tale.

This structure of the collection is a form of storytelling. It allows the overarching themes to unfold gradually as the reader progresses through the collection. There is a temptation (or perhaps a freedom) to pick where one starts when reading a collection of short stories. I support this freedom as it pertains to anthologies which contain the works of different authors. There is, however, a certain respect that I believe one must give to order and artistic intent when reading a collection produced by a single author. This is particularly relevant in this collection. If one is to fully benefit from the storytelling and the abovementioned overarching themes, I would suggest that they read it chronologically.

In her essay titled “Trauma Writing: A Beginner’s Guide”, bestselling author Jeanette De Beauvoir says the following on writing trauma: “trauma literature is about the difficulty of representing the truth of an experience so horribly extraordinary that it cannot be contained within the human mind. Its about…the simultaneous imperative to tell and the impossibility of telling.”

The complexity of writing trauma in both fiction and non-fiction is that it must be rooted in truth and sincerity. Roxane Gay echoes this in her essay, “Writing into the Wound”. She posits: “…there is a temptation to offer up your testimony, to transcribe all the brutal details as if that is the whole of the work that needs to be done…

“As with most subjects, writers can be careless with trauma. They can be solipsistic. They assume that their trauma…serves as pornography – a way of titillating the reader, a lazy way of creating narrative tension, as if only through suffering we have a story to tell.”

As mentioned in the opening paragraph, the overarching themes of this collection are grief and trauma. These themes are even more emphasised in what I call the second half of the collection. They stories are, of course, fiction. This notwithstanding, it is my opinion that Gaye’s and De Beauvoir’s positions find application here. The difficulties in expressing grief and trauma rise to the fore no matter the genre. Moreover, fiction writing is historical sociology that is not bound by the limits and constrictions of the academe. Adesanya has skilfully articulated the plots of these stories such that trauma, violence, gore and grief are not just there for the sake of shock value or the titillation of readers. I must confess, though, that at first read, I had a concern that these stories were merely intense tales of disappointment, heartbreak, trauma and violence. But upon closer inspection, I found that these were stories of the human condition. What made them particularly jarring is that Adesanya lays it all bare for all to see. The characters are complex – being both the heroes and the villains in their own stories. Some of the characters are not redeemable in their actions. The collection is an illustration of what the world truly is – nuanced.

“RÁntí Omo Eni Tí ìwo ń Se” follows the story of Peju. It illustrates how dehumanising desperation and ambition can be for all parties involved. “Fragile Façade” and “The Oddity” are stories which speak to the tragic consequences of mental health battles left unrecognised. “The Oddity” integrates African spirituality in this conversation of mental wellness. “Jemimah” relays the story of a sociopathic killer who seems to be on a path of self-awareness and self-acceptance. “Fugue”, the closing story, has a content warning, much like some of the other stories in the collection. It is a story of a devastating family secret – a type of secret that is prevalent among many African homes with girl children.

This collection is unbearable to read – not because of literary quality. It is, without a doubt, excellently written. During my reading, I would pick the book up just after I had put it away because of a graphic scene in a story. It is unbearable because of how much it requires one to go face-to-face with some of the most uncomfortable feelings and emotions. It is this discomfort that makes it an important work of literature.

Siphosethu Zazela

Siphosethu Zazela is a lawyer, author and researcher based in Johannesburg, South Africa. His latest work appears in In Other Stories (2024), an anthology of short stories published by Karavan Press. Business Day has described it as “heartbreaking” and “a standout in the collection”.