The young boy sat on the ground and watched the drying of the great puddle by the football pitch. Just two weeks ago, it was full to the knees and he’d waded there playfully with Nsama. Nsama enjoyed himself more than the boy. Maybe that’s why he’d jumped into the drainage with the rushing water that took his life. The boy had stayed inside for two weeks, and on the day he’d left the house, the puddle was drying.

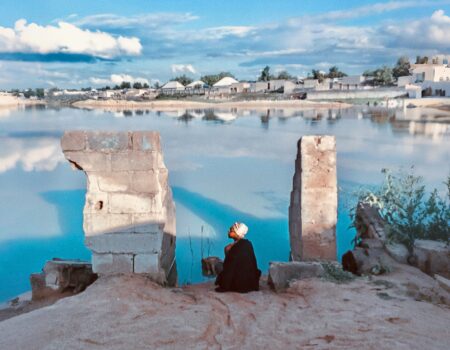

The puddle was drying, and the wind was taking the leaves of the big tree, leaving bare, sharp branches that poked the sky with their tines. Without water, the great puddle was just a hole everyone walked around. Without leaves, the tree was an angry, prickly thing that just waited. And without Nsama, the boy didn’t know who he was.

The groundskeeper was slashing the overgrown, yellowed grass that patched the field. He was dressed in a faded suit and decorated with accessories that did not fit the job he did. His gaze was fixed on the boy. His wrinkles, scars, and other lines that life had drawn were twisted in concentration.

“Everything goes away.” The boy said.

The old man’s eyes bulged, swelling like a slowly frying egg yolk. Maybe he was a harbinger of death to the old man, reminding him that the grave was calling. The boy wasn’t going to apologise. He was right.

“And where do they go?” The old man asked.

His voice carried death with it. That rasp that betrayed expiry, singing of shrinking lungs and a windpipe that now had scales due to cigarette smoke.

“The same place that Nsama went.”

The boy dipped his foot in the puddle, clenching the warm mud at the bottom between his toes. The sun boiled water couldn’t even cover his toenails. The old man cleared his throat with effortful grunts.

“Am I going the same place?” The old man asked with genuine curiosity.

“If a young boy can go, what hope is there for an old man?”

The old man stopped listening for a while. The drying sweat was starting to itch on his body. He knelt by the rim of the puddle and washed his face and forearms with the dirty water. He wiped his eyelashes with his tie and smiled at the boy. Suddenly he appeared less like a creaking bridge, and more like a well worn leather couch. One that showed off its wrinkles in a proud manner that said ‘I was there’.

“Have you seen this place?” He asked.

“It’s a mouth.” The boy said, then shook his head vigorously.

“The world is a mouth.” He reiterated.

“The world is a mouth because all it does is eat. All it knows to do is take. What goes in seconds takes years to build. We can stop people from being born but we can’t stop people from dying.”

The boy felt his body heat up as tears leaked from his eyes. His eyes were always brimming with tears lately. He felt ashamed, but the old man was smiling at him, like a father smiled at his wailing baby.

“And this mouth doesn’t give, all it does is take?”

“Yes. Everything that comes from a mouth is disgusting after all.”

“Even words?” The old man asked.

The boy stayed silent. Under the unflinching gaze of the old man, he felt like a child. He remembered he was a child.

“I’ve heard the words from this mouth, and you know what it told me?”

The young boy shook his head.

“It told me everything returns. Like the full moon, the clouds of rain, the tree leaves, the winds of cold, the migrating birds and the flying termites. These all leave but they return to stake their claim because they belong to the world, and the world guards all its things jealously. Even your friend.”

The boy shook his head, remembering all the things that were now gone forever. How could that old fool say Nsama would be back? They would never run together again. They would never climb trees and pick fruits or play in the puddle. Nsama was gone forever.

“He is not coming back.” He said.

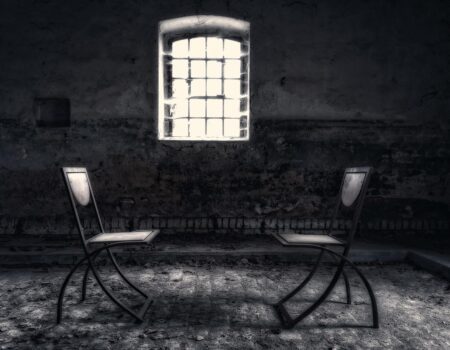

“No, he is not.” The old man agreed. “But what was he to you? What do you remember most about him? The way he looked, or the moments you shared with him?”

The boy knew what the answer was, or what the answer was supposed to be. But how could he live with that, how could his soul be satisfied with just the fact that his friend had lived? Why couldn’t he live longer, even forever? What decided such things and why did it have to be Nsama?

“The mind knew of death before we did,” the old man said. “That’s why it formed memory. The mind holds on to memories like the world holds its children. But it also knows the pain of holding on, and that’s why it also lets go.”

The old man stood up straight, brushing his wet hands against his trousers He looked around and saw that he had slashed all of the grass, but he knew it would grow again. Just as the corridors and classrooms inside would become dusty again because people would never stop moving, and the wind would always blow. Everything he swept, cut and slashed would always return. It was humbling.

“The mouth told me, your friend will always return to you. Not only the memories, but the emotions too. You will feel the happiness you felt with him with other people. You will have other friends you’ll love as you loved him.”

The old man stood up and left the young boy, whistling to the world a tune of melancholy and joy. The young boy moved his feet and he couldn’t feel the water in the puddle anymore. He looked down and found it had completely dried.

Mulenga Mupinde

Mulenga Mupinde is a Biomedical Laboratory technician in the capital of Zambia, and has worked as a Community Liason Officer under CDC. Additionally, he also concerns himself with concocting nightmares, dreams, and worlds not real to speak on reality. He was called to creating initially by cartoons, comic books and novels, but the human experience has been the most affecting thing to him. He also takes great inspiration from Zambian folk music, with Paul Ngozi being a particular highlight. He hopes to learn about himself and the world through writing, and to never confuse 'his' for 'he's' ever again.